How Britain became a world leader in COVID-19 vaccine distribution – despite other pandemic problems

Healthcare professionals draw up doses of AstraZeneca/Oxford Covid-19 vaccine at the vaccination centre set up at Chester Racecourse, in Chester, northwest England, on Feb. 15, 2021.

OLI SCARFF/AFP/Getty Images

Britain’s COVID-19 vaccination program has been envied around the world, with the country already reaching its first target of vaccinating everyone over the age of 70, most front-line health care workers and all elderly care home residents.

That’s just over 15 million people in total – or close to one quarter of the population – and the figure is rising by around 440,000 a day. It’s an impressive result that has put Britain at the forefront of the global vaccination race.

So how did Britain do it? How did a country where almost everything else has gone wrong during the pandemic – from delayed lockdowns to a botched testing program and soaring infection rates – get it right on vaccines?

Much of the credit goes to Kate Bingham, a no-nonsense venture capitalist who knew little about vaccines and even less about government procurement when Prime Minister Boris Johnson asked her to lead a vaccine task force last May. Together with a group of business people, scientists and bureaucrats, Ms. Bingham devised a novel strategy that gave Britain a crucial head start early in the pandemic.

While many countries, including Canada, were scrambling to come up with a vaccine program last spring, Ms. Bingham’s group had already zeroed in on the most promising vaccine candidates and offered to help drug companies with clinical trials and production.

They’d also started rebuilding Britain’s moribund vaccine manufacturing sector so that millions of doses could be made in the U.K. as soon as possible.

The task force moved so fast that politicians in France flew into a rage when French drug maker Valneva announced that it would make its COVID-19 vaccine in Scotland and supply Britain first, with up to 100 million doses.

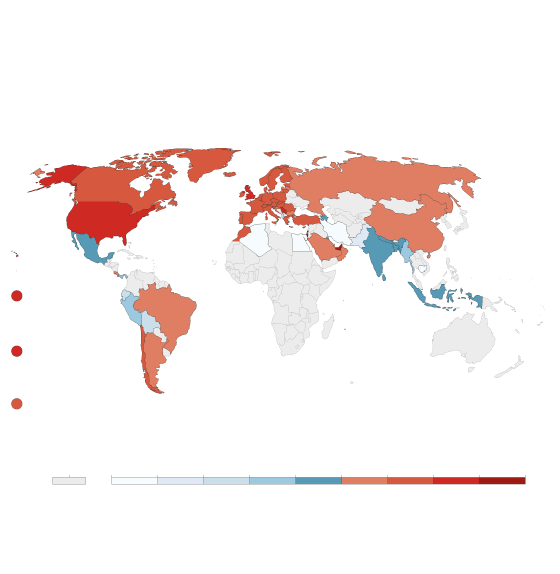

Cumulative COVID-19 vaccination

Doses administered per 100 people. This is counted as a single

dose, and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated,

depending on the specific dose regime (e.g. people receive

multiple doses).

john sopinski/the globe and mail, Source: Official

data collated by Our World in Data – Last updated

14 February

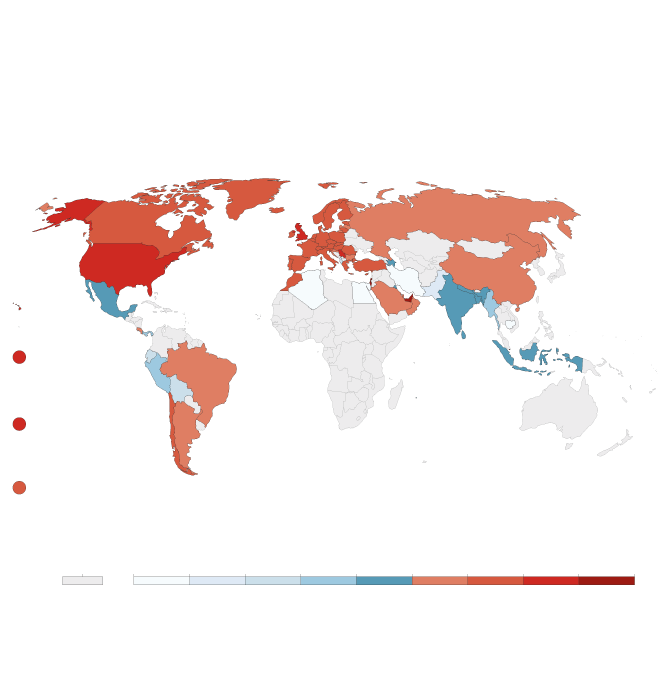

Cumulative COVID-19 vaccination

Doses administered per 100 people. This is counted as a single

dose, and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated,

depending on the specific dose regime (e.g. people receive

multiple doses).

john sopinski/the globe and mail, Source: Official

data collated by Our World in Data – Last updated

14 February

Cumulative COVID-19 vaccination

Doses administered per 100 people. This is counted as a single dose, and may

not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on the specific

dose regime (e.g. people receive multiple doses).

john sopinski/the globe and mail, Source: Official data collated by

Our World in Data – Last updated 14 February

“She was able to unite the team swiftly and with a purpose,” Steve Bagshaw, a biotechnology veteran who served on the vaccine task force, said. “She created a single sense that this was really, really important.”

Ms. Bingham had never worked on vaccines before. She’d spent 30 years in the biotech sector searching for promising startups with new therapeutics. Although she knew next to nothing about vaccines, she soon discovered that her experience in analyzing scientific projects and determining which would succeed was an invaluable asset.

She also had deep connections in business and politics. She’d attended the University of Oxford with Mr. Johnson, and her husband, Jesse Norman, is a junior cabinet minister. That generated some initial controversy over cronyism, but also helped Ms. Bingham when she needed cabinet ministers to make quick decisions on vaccine contracts.

The task facing her in May was daunting. It’s often hard to remember that when the pandemic struck last February, the prospect of a vaccine seemed remote.

No one had ever made a successful jab against a coronavirus and scientists thought it would take well over a year to develop one that worked. And even though researchers and drug companies launched around 200 vaccine projects, few were expected to succeed.

Meanwhile, governments around the world were jockeying to snap up whatever vaccine became available.

“This was a gargantuan challenge,” Ms. Bingham said during a recent press briefing. “Our task was to get the most promising vaccines as soon as possible.”

Even if Ms. Bingham could secure a vaccine, Britain had almost no capacity to make it. While Britain was a world leader in medical research, the country’s vaccine-making capability had shrunk to just two plants – one that made seasonal flu shots and another that produced a niche vaccine against Japanese encephalitis.

Ms. Bingham did have one early advantage: Researchers at the University of Oxford had started work in January on one of the more promising vaccine projects, based on a new technology that involved using a weakened cold virus found in chimpanzees and genetically manipulating it to look like part of the COVID-19 virus.

It was harmless when injected into humans, but triggered the body’s immune system to fight the virus. By May, researchers had launched clinical trials and several biotech firms had begun informal talks to see if they could make the vaccine.

There was still no guarantee it would work. “I asked the vaccine experts: What is the likelihood of success for these vaccine candidates?” Ms. Bingham told the U.K. House of Commons public accounts committee last month. “Across the board, the feedback was that vaccines that were already in [trials] probably had a 15 per cent chance of success, maybe 20 per cent, and vaccines that were yet to go into [trials] we should assume had a less than 10 per cent chance of success.”

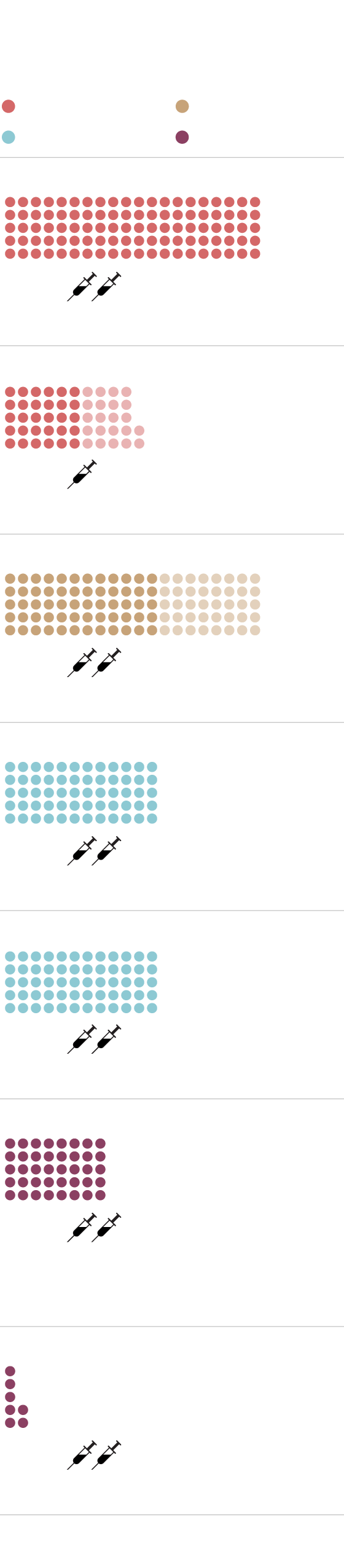

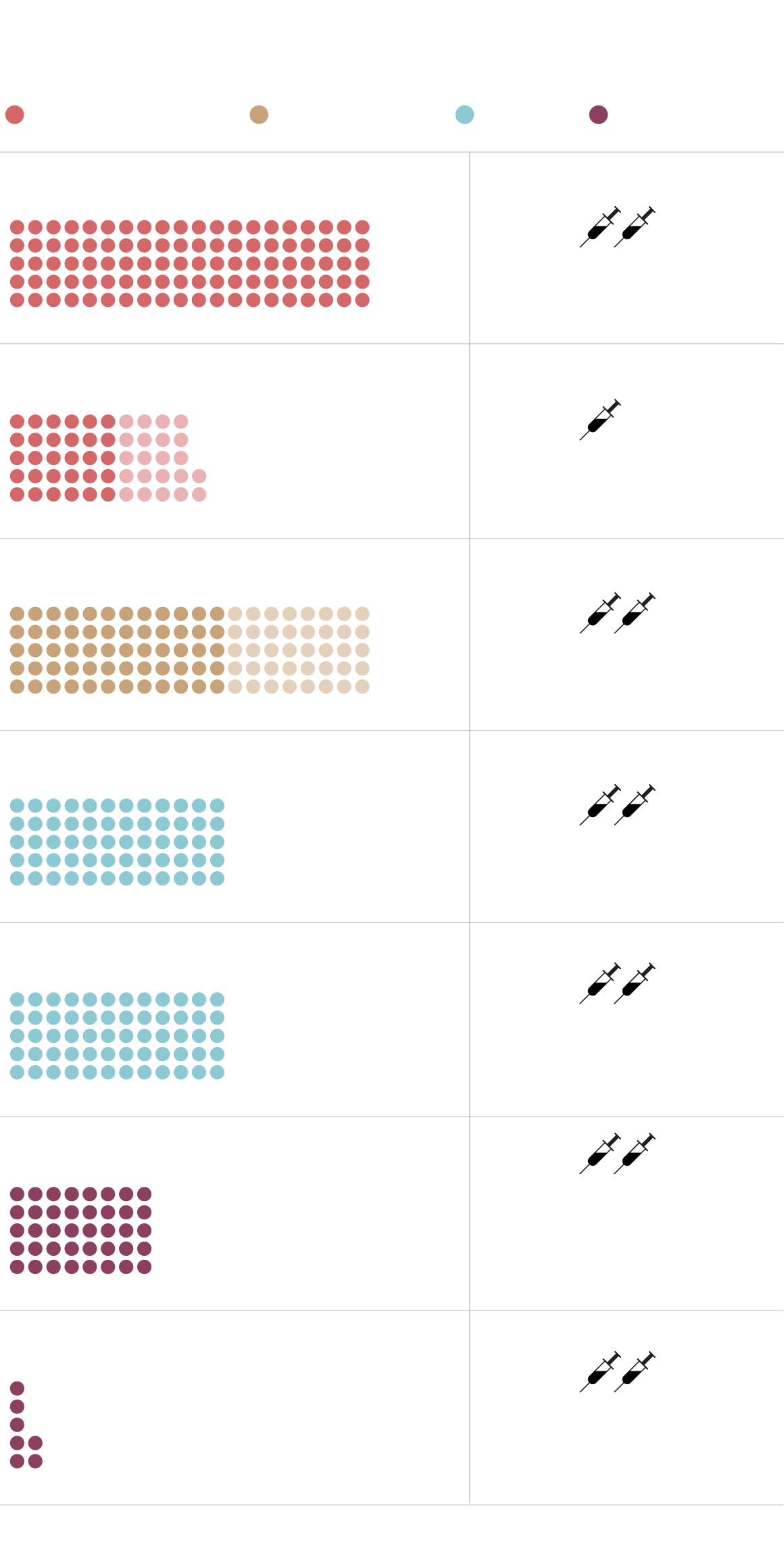

BRITAIN’S CONFIRMED SOURCES OF COVID-19 VACCINES

Millions of doses

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Janssen/Johnson & Johnson

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Status: Preclinical stage

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Status: Temporary authorization granted

by Medicines and Healthcare products

Regulatory Agency

Status: Filed for conditional approval

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: BRITISH GOVERNMENT

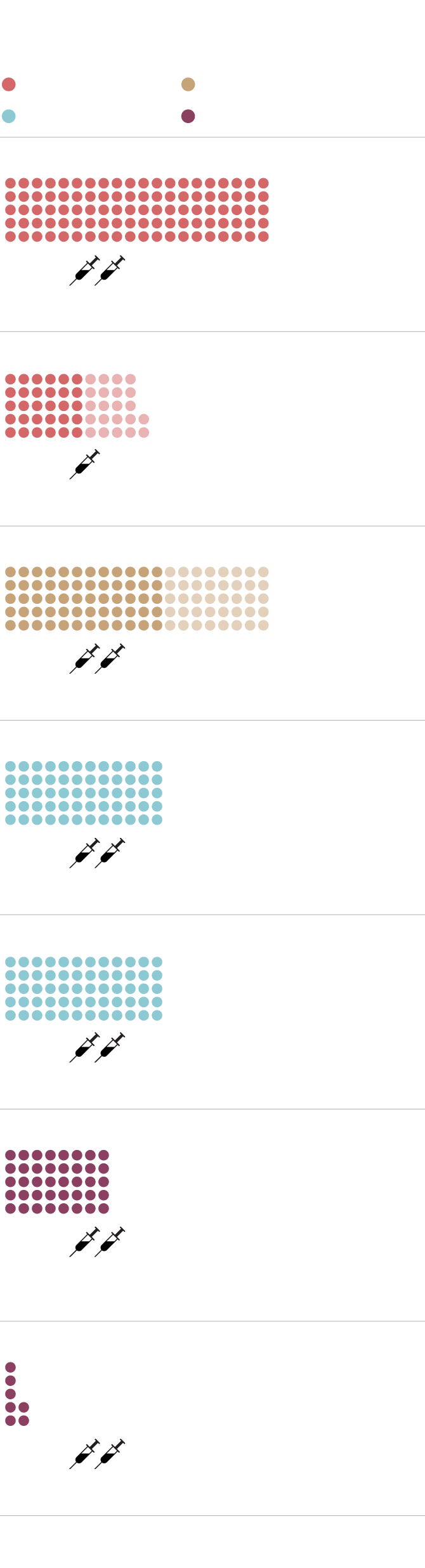

BRITAIN’S CONFIRMED SOURCES OF COVID-19 VACCINES

Millions of doses

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Janssen/Johnson & Johnson

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Status: Preclinical stage

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Status: Temporary authorization granted by Medicines

and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

Status: Filed for conditional approval

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: BRITISH GOVERNMENT

BRITAIN’S CONFIRMED SOURCES OF COVID-19 VACCINES

Millions of doses

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Janssen/Johnson & Johnson

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Status: Preclinical stage

Status: Phase 3 in progress

Status: Temporary authorization

granted by Medicines and

Healthcare products

Regulatory Agency

Status: Filed for

conditional approval

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: BRITISH GOVERNMENT

Since she couldn’t bank on one candidate, Ms. Bingham reached out to industry colleagues to help pick other potential winners.

“It was a simple task,” joked Clive Dix, a former drug company executive and member of the vaccine task force. “She said, ‘We need the top 10 vaccines for the U.K. There’s only 200-odd [candidates] out there – just go out and tell us which is the best.’”

Task force members began poring over data from various vaccine trials and setting up teams to study about a dozen of the most promising candidates.

They quickly prioritized the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, which was showing strong results from its messenger RNA technology – molecules that instruct the body to produce a harmless protein that resembles part of the COVID-19 virus and alerts the immune system.

Even though U.S.-based Moderna was developing a similar mRNA vaccine at the time, which also looked good, Ms. Bingham worried the company would favour its home market. Pfizer was also American but its partner, BioNTech, was based in Germany and had an established European supply chain.

The task force went with Pfizer-BioNTech, and Britain was the first country to sign a deal with the company in July.

A similar calculation was made about the Oxford vaccine. At first, Oxford researchers planned to team up with a subsidiary of U.S. drug giant Merck as a manufacturing partner.

British officials quickly steered them toward AstraZeneca, a British-Swedish company, out of the same fear that Merck would be beholden to the U.S. market, especially as long as Donald Trump remained president. Once again, Britain was first country to sign an order for the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine last spring.

Ms. Bingham didn’t stop there. Since both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca projects involved novel platforms, the task force looked for more conventional candidates that had a better chance of success. They settled on projects at U.S.-based Novavax; Johnson & Johnson, which is also American; and France’s Valneva. All used tried and tested vaccine platforms.

Britain wasn’t alone at the time in trying to pick vaccine projects. Canada bet on a joint venture between the National Research Council and China’s CanSino Biologics Inc. – but the relationship fizzled out in August.

France’s hopes for a vaccine developed at the country’s prestigious Pasteur Institute fell apart in January when test results showed it had limited effectiveness. Another French vaccine project, a joint venture between France’s Sanofi and Britain’s GlaxoSmithKline, has been delayed until the end of the year because of problems during clinical trials.

Once Ms. Bingham’s team selected the vaccines to go after, they devised a unique approach to win contracts. She knew Britain couldn’t compete on price with large buyers such as the U.S. and the European Union, so they came up with a “U.K. offer” – a package that included more than just buying doses.

The task force offered drug companies help in conducting clinical trials in order to speed up regulatory approval. They worked with the National Health Service to set up a registry of nearly 400,000 people who were willing to serve as trial participants.

They also organized the world’s first human challenge trials where volunteers were deliberately infected with COVID-19 to test the efficacy of vaccines. That avoided the need to wait months for participants in regular trials to become infected naturally.

Britain’s drug regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, got involved as well and agreed to conduct rolling reviews of trial data to further accelerate the approval process.

Like many countries, Britain provided incentives for drug companies to make their vaccines domestically, but the task force went further. They realized that one of the key steps in the manufacturing process involved putting the vaccine into vials, and those facilities were in short supply.

So they turned to India’s Wockhardt Ltd., which had a plant in Wales that made drugs for diabetes, anticoagulation and pain management. The task force signed an 18-month agreement to reserve one of the plant’s production lines for the exclusive use of British vaccine makers.

To further domestic production, the task force created a Vaccines Manufacturing and Innovation Centre, which will not be fully operational until summer but has already been pumping out millions of doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine since its approval in December.

The task force has also spent £100-million buying a factory that used to make veterinary medicines, converting it into a vaccine facility.

Canada has found it much harder to develop domestic vaccine production. Procurement Minister Anita Anand told a parliamentary committee recently that she tried to entice drug makers to manufacture their vaccines in Canada, but was told Canadian facilities were too limited.

The federal government also committed $126-million for a new biomanufacturing facility in Montreal, but the project has been delayed and won’t start producing vaccines until the end of 2021.

The lack of local manufacturing has left Canada vulnerable to recent production issues at Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, which have reduced supplies.

The American government has also moved to protect the production of vaccines made in the U.S., which has also limited a potential supply line for Canada. Britain has been less affected by the slowdowns at Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna because the country has shifted largely to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, which is made in the U.K.

For drug makers such as U.S.-based Novavax, Britain’s approach proved unbeatable. The company conducted nearly all of its drug trials in the country, using 15,000 volunteers, and received government funding to start making the vaccine in Britain while it waits for regulatory approval.

Last month, Novavax released data showing their vaccine was 89-per-cent effective and provided 85.6-per-cent protection against the British variant of the virus. Novavax is expected to seek authorization in Britain first, putting the country at the head of the line for doses as early as this summer.

France’s Valneva has also begun producing its vaccine in Scotland, thanks to £1.3-billion in British government funding. The vaccine is expected to be ready for regulatory approval in spring and Britain is on the company’s priority list for up to 100 million doses, with some arriving this summer. Countries in the EU, including France, won’t get it until next year.

That hasn’t been lost on some French politicians, who have complained about the country’s slow vaccine rollout. Britain “rolled out the red carpet for this company, helping with financing and the set-up,” Christelle Morancais, the regional council president in Loire, where Valneva is based, told the Associated Press last week. “And we were powerless.”

In another collaboration announced this month, Germany’s CureVac plans to work with Britain’s genome sequencing group, which has been a world leader in tracking genetic changes to the virus, to develop and manufacture mRNA vaccines aimed specifically at new variants.

“The U.K. government and its Vaccines Task Force has been at the forefront of surveillance, vaccine development and delivery of vaccines for deployment during this pandemic,” the company said in a statement.

In total, the task force has signed deals worth close to £3-billion for 367 million doses from Pfizer-BioNTech, Oxford-AstraZeneca, Novavax, Valneva and Johnson & Johnson. A smaller agreement with Moderna was signed last month. Ms. Bingham said Britain paid roughly £10 a dose for the vaccines, which is comparable to what the U.S. spent.

With the supply in place, Britain launched one of the world’s first COVID-19 vaccination programs at 6:30 a.m. on Dec. 8, when 90-year-old Margaret Keenan rolled up her sleeve for a shot of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in a hospital in Coventry.

Since then, the number of vaccinations has grown from around 300,000 a week to nearly 400,000 a day. The government has set up 50 mass vaccination sites at sports stadiums, cathedrals, convention centres and museums.

The rollout picked up after health officials announced that the interval between first and second dose would be extended from two weeks to up to three months. It was a controversial decision that went against the drug makers’ recommendations.

The government said it had no choice because of escalating infection rates and the delay would ensure a greater number of people received an initial shot. Other countries, and some Canadian provinces, have since followed suit.

The most effective part of the British vaccine rollout has come from local doctors, hospital hubs and community clinics. Thousands of doctors have worked furiously to administer doses and contact everyone eligible, sometimes using volunteers to go door-to-door.

Many have banded together in regional vaccination sites that became so efficient at administering vaccines they were told to slow down so that cities such as London could catch up.

“It feels everyone is right into it,” said Simon Opher, a doctor in Dursley, northeast of Bristol. “There’s a sense of celebration about it.”

Plenty of challenges remain. The take-up for vaccines has been far lower in some Black, Asian and other ethnic communities.

Health officials will also soon start administering second doses for people who had their first shot in December. That could slow down the overall program and present logistical headaches as officials try to keep track of who has been immunized.

Concerns have also been raised about the effectiveness of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine in elderly people and against the South African variant.

Ms. Bingham stepped down from the task force in December, and most of the rollout is now managed by the NHS.

“I am very happy with what we have done,” Ms. Bingham told the parliamentary committee. “Even knowing what I know now, I would still do it again.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.