How SoftBank’s dalliance with Greensill ended in disaster

In October 2019, the head of SoftBank’s $100bn Vision Fund phoned Lex Greensill, wanting to dispel a troubling rumour.

Rajeev Misra, who runs the largest private investment fund in the world, had backed Greensill’s finance company heavily, pouring in $1.5bn over a few short months.

Greensill had also won the personal admiration of SoftBank’s founder Masayoshi Son, Japan’s richest man, who started introducing the Australian financier to world leaders and major investors. Son told them his new apprentice had a miraculous gift for financial engineering, which could bring to life even the most extravagant projects.

But now Misra was hearing that Greensill was lending more and more money to controversial metals magnate Sanjeev Gupta.

Misra thought the company had cut ties with Gupta after an earlier scandal involving the tycoon and a Swiss asset manager. He was now being told the opposite. He had a simple question for Greensill: how exposed was his company to Gupta’s opaque web of ageing industrial assets?

The smooth-talking Australian was initially reassuring, explaining that Greensill Capital itself had zero exposure to Gupta’s companies. Yet when Misra followed up with a question about Greensill’s banking subsidiary in Germany, he learned a startling fact.

Lex Greensill conceded that there was a “reasonable wedge” of exposure related to Gupta in Greensill Bank. He then provided a more precise figure: about €1.5bn.

Misra was stunned. Weeks earlier SoftBank had been humiliated by the failure of WeWork’s initial public offering. Now he was discovering that a second portfolio company that SoftBank had lauded as revolutionary and disruptive was also built on shaky foundations.

This might have proved a turning point in the relationship. But rather than distancing itself from Greensill, SoftBank got even closer. Greensill began to prop up some of the Vision Fund’s weakest investments. At the same time, Misra worked behind the scenes to shore up the finances of both Greensill and Gupta.

The strategy ultimately failed. Greensill Capital filed for bankruptcy in March this year, sparking a corporate and political scandal, while wiping out the Vision Fund’s investment. Greensill’s lending to Gupta’s GFG Alliance is now the subject of a criminal investigation in both Germany and the UK.

Colin Fan, the senior SoftBank executive who spearheaded the investment, left the Vision Fund earlier this year. Son, meanwhile, cut an uncharacteristically humble figure at SoftBank’s annual results presentation in May, referencing Greensill while presenting a slide titled “Many Regrets”.

Greensill’s collapse has harmed other companies in the Vision Fund, most dramatically construction start-up Katerra, which borrowed heavily from its sister company and filed for bankruptcy last month.

Credit Suisse, which invested client money in Katerra debt via Greensill, is gearing up to sue SoftBank. Relations are now so frosty the Swiss bank has even recalled personal loans it previously extended to Son.

While SoftBank took steps to protect itself from the fiasco — shrewdly never appointing formal directors to Greensill’s board — its investment enabled a buccaneering approach to risk, while allowing the company’s founders to cash out hundreds of millions of dollars.

Crisis averted

Winning SoftBank’s patronage was a moment of triumph for Lex Greensill. He had spent weeks wooing executives at the Japanese technology conglomerate, even bringing former British prime minister David Cameron — who was now his boardroom adviser — on a trip to Tokyo to meet Masayoshi Son, according to people familiar with the meeting.

Interviewed on the day the Vision Fund’s $800m investment became public in May 2019, Greensill presented an image of a cutting edge financial technology firm with “over 8 million customers”.

However, a due diligence report SoftBank produced ahead of investing flagged that nearly three-quarters of Greensill’s 2018 revenues had come from just five clients. Even more concerning, in 2017 one client alone had accounted for $70m of its $102m net revenue: Sanjeev Gupta.

The Indian-born industrialist was a key player in an unresolved investment scandal that was public knowledge when SoftBank first invested in Greensill. Swiss asset manager GAM was in the process of liquidating a $7bn fund range, which had run aground after investing heavily in hard-to-sell bonds Greensill had brokered for Gupta.

SoftBank’s due diligence report concluded that Greensill faced “minimal legal or regulatory risk”. This optimism was partly based on the “expectation that GAM clients ultimately will profit” when the Greensill investments were repaid.

It is not clear, however, whether SoftBank was aware that it would facilitate that repayment.

While Lex Greensill emphasised his company’s tech prowess, over half of SoftBank’s investment was ploughed into a distinctly old-world institution: a near century-old bank in Bremen, which the company had acquired and rebranded five years earlier.

By recapitalising its German banking subsidiary, Greensill now had the capacity to provide Gupta with a €2.2bn loan, giving him enough funds to buy back the remainder of his bonds from GAM.

It was the second time in less than a month that SoftBank had propped up a scandal-plagued European financial services firm, having agreed to pump $1bn into Germany’s Wirecard weeks earlier. Within two years, both would collapse, sparking two of the continent’s biggest recent corporate scandals.

The money guy

In August 2019, SoftBank was enduring a very public humiliation.

The Japanese conglomerate and its Vision Fund had poured $10bn into WeWork, the shared office business whose stated mission was “elevating the world’s consciousness”. But the company was now finding it much harder to raise money at an IPO: public equity investors were unmoved by WeWork’s grandiose claims, refusing to look past its record of heavy losses.

With the debacle increasingly tarnishing SoftBank’s reputation, Masayoshi Son presented an alternative funding proposal to WeWork’s founder Adam Neumann: borrow billions of dollars from Greensill Capital instead.

Lex Greensill was on holiday with his family in France when Son summoned the financier to Tokyo. In Japan, they devised a plan to lend $3bn or more to WeWork, secured against rent payments from the company’s tenants. One person involved in the negotiations said that while this could have worked on a small scale, he did not believe that Greensill had the distribution capacity to lend the company billions of dollars.

“You put Masa and Lex in a room together and you get some seriously crazy shit,” he said. “This was a great example of that.”

In the end, Neumann torpedoed the idea before Greensill’s capacity was tested. After a tense meeting with Son and Greensill in Tokyo, the WeWork founder started referring to the financier as “Lex Luthor” — Superman’s arch-nemesis — according to the new book The Cult of We.

While Greensill did not ultimately lend to WeWork, documents seen by the FT show that it did get to the stage of naming its proposed lending programme. The finance firm frequently named its debt facilities after landmarks in Lex Greensill’s hometown of Bundaberg. WeWork’s would have been “Hummock”, an extinct volcano where the financier’s grandparents had established his family’s farm in the 1940s.

The rescue loan was just one of a string of fanciful financing schemes Greensill said he could deliver to Son.

The SoftBank founder believed that the financier could fund a series of futuristic “smart” cities around the world. One plan involved modernising Mecca for visiting pilgrims. Another, building a new Indonesian capital city.

In February 2020, Greensill travelled to Indonesia with Son, who introduced him to the country’s president Joko Widodo and former British prime minister Tony Blair, who was also involved in the scheme.

As Greensill shook hands with the Indonesian president, Son introduced him using an affectionate nickname he had recently coined: “the Money Guy”.

Circular financing

One month later, money was in short supply at Greensill.

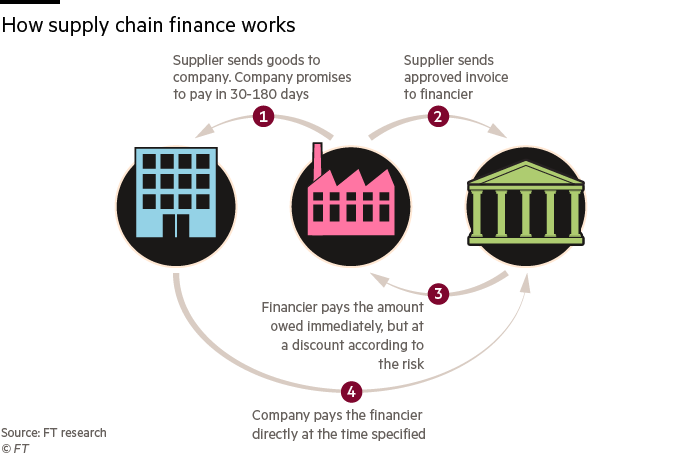

After the GAM fiasco, Credit Suisse had stepped into the breach and become the company’s main funding source via a $10bn range of supply-chain finance funds that bought Greensill’s invoice-backed debt products. But as the coronavirus pandemic upended markets in March 2020, the Swiss bank’s rattled clients started withdrawing billions of dollars from the funds.

As the exodus accelerated, Lex Greensill began lobbying to gain access to an emergency Bank of England lending scheme, telling officials in March that for the whole supply chain finance industry, “liquidity could well become a major issue in the coming days”.

After encountering resistance from the government, Greensill’s adviser David Cameron barraged ministers and civil servants with phone calls and text messages imploring them to reconsider. But in the end, Lex Greensill made the call that halted the stampede.

After ringing Son and asking for assistance, SoftBank quietly injected more than $1bn of its own cash into the Credit Suisse funds. To the outside world, it appeared that the rout had ended.

“If SoftBank didn’t put the money in, and the funds continued to have a run on them, it could have become self-fulfilling,” said one person close to the situation, describing the investor withdrawals as “quasi-existential”.

SoftBank’s support came at a price, however. In exchange for propping up the Credit Suisse funds, the Vision Fund received more equity in Greensill Capital, according to two people familiar with the deal, leaving it with a 40 per cent stake.

The arrangement was fraught with potential conflicts of interest. Greensill had begun using the Credit Suisse funds to finance some of the weakest companies in the Vision Fund, such as struggling car subscription start-up Fair. Unbeknown to other investors, Greensill and SoftBank were now effectively channelling a circular flow of financing through the funds.

Greensill was able to justify lending to start-ups often with little in the way of physical assets because it claimed the loans benefited from a SoftBank guarantee, according to people involved in structuring them and documents seen by the FT. A person close to SoftBank denied there was a guarantee.

One document detailing the structure shows that Greensill itself would eat the first slice of any losses, minimising the impact to SoftBank’s balance sheet “due to the extreme remoteness” of their guarantee “ever being called”. The disputed backstop was vital for insurers, who would only underwrite the risk on that basis.

Months later, the intricate financial tapestry began to unravel. In June 2020, the FT revealed that SoftBank had quietly invested in the Credit Suisse funds, prompting an internal review at the Swiss bank. Ultimately, the Japanese conglomerate withdrew its cash

By September, the insurers pulled out. Greensill’s problems began to compound.

The last gamble fails

One year after Misra first learned of Greensill Bank’s exposure to Gupta’s industrial empire, German regulator BaFin was increasingly alarmed at the level of risk tied to a single client. A special auditor began probing its books in September 2020.

Then in October, Gupta revealed an audacious bid for Thyssenkrupp’s steelmaking unit. By raising financing against a new asset, Gupta could recycle some of his companies’ existing Greensill debt and alleviate pressure on his main lender, according to people familiar with the plan.

“Lex believed that Gupta would buy Thyssenkrupp and that would bail him out,” said one person close to the deal.

Misra, who had previously been one of Deutsche Bank’s most senior traders, rang up his former colleagues and asked whether Germany’s largest bank could back Gupta’s bid for the steelmaker, according to four people familiar with the calls.

Deutsche Bank did not extend any financing, however, with one banker describing the proposal as “laughable”.

Around the same time, Greensill’s mounting problems were getting closer to home for SoftBank. Its portfolio company Katerra needed to restructure its debt, including loans Greensill had extended through the Credit Suisse funds.

In November, SoftBank wired Greensill $440m to cover losses the restructuring would inflict on the Swiss bank’s funds. The Japanese group again extracted more equity, its stake creeping up to 49 per cent.

Then in December, BaFin started imposing limits on Greensill Bank while pressing it to reduce its Gupta-linked exposure — which by that point had swelled close to €3bn.

“Everyone was in crisis meetings,” said one person close to SoftBank. “They realised it wasn’t just a Katerra problem, it was a Greensill problem.”

The fiasco was the primary reason Fan left the Vision Fund in January, according to people close to the decision. SoftBank said: “Fan’s departure was unrelated to Greensill.”

Around this time, SoftBank wrote down the value of its Greensill stake down to zero. But executives also realised that their recent $440m cash infusion had never actually made it to the Credit Suisse funds.

On February 1, Rajeev Misra joined a conference call with Lex Greensill, Sanjeev Gupta and officials from BaFin to discuss a plan for winding down the bank’s troublesome exposure.

Greensill had earlier hoped that SoftBank might take on some of the loans, according to two people close to the talks. But Misra was in no mood to offer any more assistance to its wayward portfolio company.

“After the call, it was very clear SoftBank was not able to do this,” one of the people said.

One month later, Greensill Capital — and the billions of dollars SoftBank had invested — were gone.