Banking on cannabis: the new network of lenders for a semi-legal industry

When Scot Garrambone and his partners in California started selling weed in 2018, they had hoped to make a lot of money. They just didn’t expect to spend so much time counting it.

Their company, Dreamfields, based in the small town of Desert Hot Springs, pulled in more than $2m in revenue that year, all of it in cash, according to Garrambone. The group couldn’t take electronic payments and there was no bank willing to hold their deposits. This left Garrambone and his colleagues, who had self-funded their business in the absence of any bank loans, to deal with the money — and the risk of theft — themselves.

“We would spend the entire day just counting and paying people in cash. We did that for about a year,” says Garrambone, Dreamfields’ chief financial officer.

Cannabis companies such as Dreamfields are caught in a gap between state and federal law. Despite California making weed legal for recreational use in 2016, the federal government still classifies marijuana as an illegal substance. With top US banks such as JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo and payments companies including Visa and Mastercard adhering to federal law, they have opted out of serving cannabis companies.

But now three years later, Garrambone says Dreamfields is doing almost all of its transactions electronically, taking out loans and making deposits.

This is despite the lack of meaningful progress at the federal level to bridge the gap with state law. Instead, relief has largely come thanks to a small group of financial services companies that has sprouted up to cater to the cannabis industry.

“I say now we probably do about 98 per cent of our payments electronically and we bring everything into the bank,” Garrambone says.

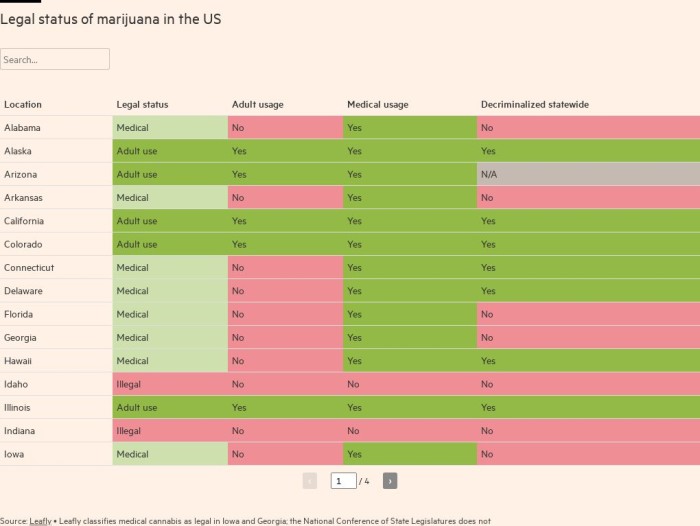

Since 2012, 18 states, and Washington DC, have legalised cannabis for recreational use and 36 permit smoking it for medical reasons, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Industry tracker New Frontier Data estimates the market for legal cannabis was worth about $20bn in sales in 2020 and predicts it will more than double by 2025 to $41.5bn.

With numbers such as that, cannabis can make a credible claim of being the largest underbanked industry in the US.

This is not for lack of trying by some lawmakers. The House of Representatives passed the Secure And Fair Enforcement, or SAFE, Banking Act in 2019 but it floundered in the Senate. The bill would make it explicit that federally regulated banks are allowed to work with cannabis companies in states where marijuana is legal.

The bill passed the House again in April with bipartisan support. It has been sent back to the Senate where its prospects are unclear. Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader, added some momentum to normalise federal treatment of cannabis in August when he published a separate draft bill to legalise marijuana.

Given the size of the cannabis industry, someone was bound to try and fill the vacuum. In the absence of federal action, a new network of companies has sprung up to service the industry, often charging lucrative fees they would be hard-pressed to receive elsewhere.

“The cannabis industry desperately needs access to financial services,” says Karan Wadhera, managing partner at Casa Verde, a fund which invests in companies in the cannabis industry. “We think companies targeting this problem are among the most compelling businesses in the industry from an investment standpoint.”

In the weeds

When the first states voted to legalise recreational marijuana in 2012, the industry was by and large self-funded, or used cash from friends and family or niche groups of private investors. Loans were scarce.

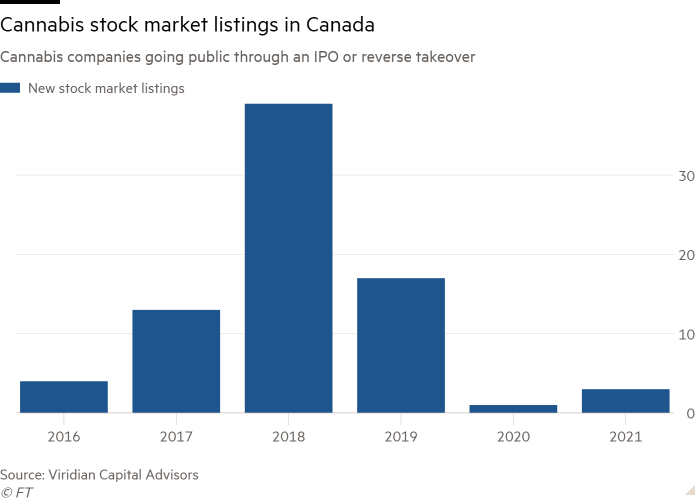

The industry got a fresh injection of equity funding starting in 2016 with a string of public listings on stock exchanges in Canada, where cannabis companies have smoother access to financial services. The early hype around many stocks faded, however, when growth underperformed expectations.

Between 2016 and 2019, 73 cannabis companies went public in Canada through initial public offerings and reverse takeovers, but there have only been four new listings since 2020, according to Viridian Capital Advisors, a cannabis-focused financial and strategic advisory firm.

“The vast majority were not performing and that sucked a lot of enthusiasm from the industry,” says Ariella Morrow Tolkin, managing director at Jefferies and head of the bank’s cannabis practice.

Around the same time as the market for Canadian listings waned, direct lenders, which raise money from investors with the aim of making loans, began to emerge to provide debt financing to cannabis companies.

They have been tapping into a seller’s market. “For the most part, US cannabis companies have been starved of capital. There are financing sources that have popped up over the last 12-18 months,” Tolkin says. “They have higher headline lending rates compared with financing rates of companies with similar profiles operating in other sectors but they are the way for this industry to get capital right now.”

AFC Gamma, a commercial real estate finance company or Reit, this year raised $119m through an IPO to lend to cannabis companies in the first deal of its kind on the Nasdaq stock exchange.

Another is Bespoke Financial, which since 2019 has originated more than $140m in loans across seven states, including to Dreamfields. “It’s really been drinking from a fire hose for the last two years,” says George Mancheril, Bespoke Financial’s co-founder and chief executive.

Cannabis in the US is still a highly fragmented industry with an estimated 27,000 companies which handle marijuana, according to Jefferies. Borrowing costs vary widely, with industry participants and lenders saying rates can be as low as 8 per cent per year, but more typically range between 12 per cent and 20 per cent, depending on the borrower’s size and what they’re able to offer as collateral.

This is well in excess of what comparable non-cannabis companies would expect to pay. However, greater competition among lenders has reduced rates from the high levels seen just a few years ago.

“Rates have come down significantly. When I first started talking to lenders I knew in this space, they were quoting between 18 and 26 per cent,” says Michael Schwamm, a partner at law firm Duane Morris who advises companies and investors in the cannabis industry.

With interest rates at record low levels, the rates lenders can charge cannabis companies is proving compelling to investors. “Considering the prevailing rates of the market, if you can get 10 per cent, 13 per cent yields you look like a hero,” says Scott Geiper, president and founder of Viridian Capital Advisors.

Companies that went public in Canada and have access to the country’s public debt markets have also seen borrowing costs come down. They have been boosted by the sector’s improving creditworthiness as it matures, as well as investors’ search for yield, according to Steve Winokur, global head of cannabis investment banking at Canaccord Genuity.

Ayr Wellness, a US multi-state cannabis operator which went public on Canada’s NEO exchange in 2019, borrowed $110m in bonds last year, paying interest above 13 per cent. The bonds have rallied to trade at a yield of 8.8 per cent, a sign of increased investor demand. It’s a long way off the roughly 4 per cent yield on a widely watched high-yield bond index, or even the 7.2 per cent yield on an index of lowly-rated, triple-C bonds.

“When yields are this low, people reach for riskier assets to find yield,” says Jonathan Sandelman, Ayr’s chair and chief executive. “We as an industry, at least the best players, have become very attractive to invest in.”

The inability to make deposits made cannabis businesses a target for burglaries. But now more local banks and credit unions are stepping in to take deposits and give cash management services.

Dime Community Bank takes deposits and offers cash management services to cannabis companies, primarily in the New York metropolitan trade area including New Jersey, Connecticut and Pennsylvania, but does not yet lend money to the industry. Sarah Limones, a compliance officer at Dime, says the business requires more frequent compliance checks, with regular reviews as often as once a month compared with annually for businesses operating in industries with more clear-cut regulations.

San Francisco-based Dama Financial does compliance work for smaller banks, which want to serve cannabis companies but have limited capacity to carry out due diligence. This allows cannabis businesses to take out loans as well as make deposits, process electronic payments and arrange for armoured car cash pick-ups.

“It’s not safe to have seven figures sitting in your back office,” says Eric Kaufman, Dama’s chief revenue officer.

Some state governments have also introduced programmes to ensure the gains from the cannabis industry are spread more proportionally throughout different societal groups, including African Americans. Illinois, for instance, has expunged thousands of prior cannabis-related arrests which can make an applicant ineligible for a dispensary licence, and raised a “social equity” loan fund worth up to $34m.

Seke Ballard, chief executive of Good Tree Capital which is one of the administrators for the Illinois loan programme, estimates that the average loan made through the fund will be above $150,000 and that interest rates will not exceed 8 per cent, giving it one of the industry’s lowest borrowing costs.

Pot of gold

Despite the progress, there’s still “a lot of ground to cover for these companies to bank in a regular way” and “in a way that’s not overly burdensome to them in terms of fee structure”, says Matthew Kittay, a partner at law firm Fox Rothschild who works with and advises cannabis companies.

The limited pool of lenders means borrowing costs remain considerably higher than other industries. The “tax on cannabis” companies for borrowing is still up to 600 basis points higher than for a comparable non-marijuana business, says AFC Gamma chief executive Leonard Tannenbaum.

Tannenbaum believes the companies his firm lends to would get a lift of at least 10 per cent in revenue if Visa or Mastercard would process their payments.

A burdensome tax rate is another hurdle. Given that cannabis is still illegal at the federal level, the Internal Revenue Service forbids businesses trafficking in controlled substances from writing off routine business expenses such as salaries and rent, driving tax bills higher.

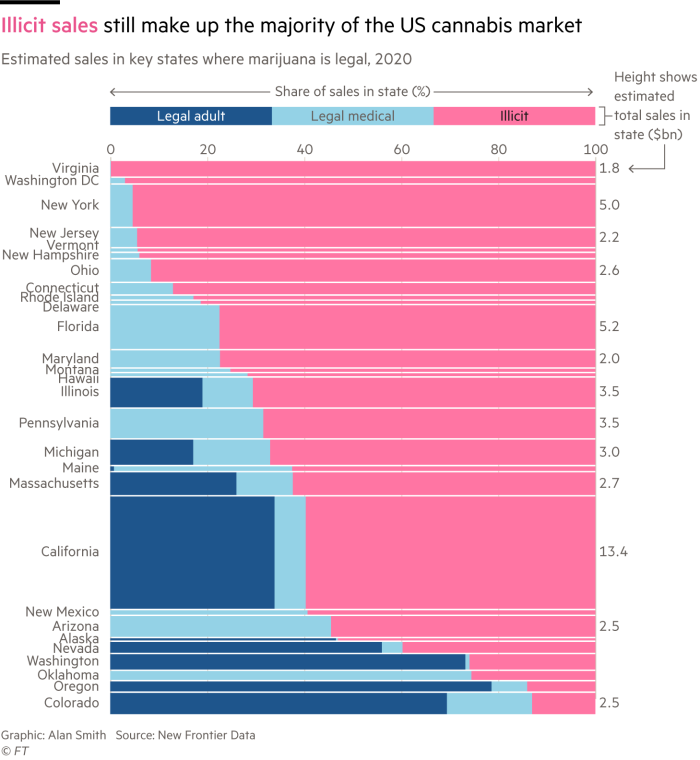

The higher costs can stunt growth for new entrants, while for existing businesses they can elevate prices in a market where the chief competition is from illicit sellers, which do not need to budget for compliance costs, banking fees and tax bills.

The illicit cannabis market was worth $66bn in 2020, more than three times the size of the legal market, New Frontier Data estimates. This was chiefly from states which have not yet fully decriminalised cannabis but illicit sellers are also competitive in states where consumers can make legal purchases. In California, legal cannabis sales for recreational use totalled $4.5bn, dwarfed by the estimated $8bn in illicit sales.

For the companies themselves legalisation would be a boon. But for these financial service providers, there are questions about what will happen to their models once mainstream banks get the green light to enter the industry, and whether this period of higher lending rates will eventually vanish.

One hope for these performers is that banks will be reluctant to dive into cannabis banking even if it becomes federally legal.

“For maybe some of the largest players who’ve gone public on Canadian exchanges with public financials, those are the ones that are low-hanging fruit for banks,” says Wadhera from Casa Verde, whose investments include Bespoke. “But for the most part it will not be overnight. That’s normal for any industry that’s been under the sort of scrutiny that cannabis has been under.”

A rough proxy could be the industry for hemp, a strain of the cannabis plant which was decriminalised at the end of 2018. Since then, the industry’s access to banking services has improved — for example, hemp health supplement maker Charlotte’s Web has been granted a $20m credit line by JPMorgan.

However, some big firms are still selective about what they will do in the area. Wells Fargo says the legality of cannabidiol (CBD) production and distribution “is extremely complex” and so the bank considers banking relationships “on a case-by-case basis” and conducts “comprehensive due diligence” before entering into them.

American Express says the payments company does allow for the sale of hemp or CBD products but only if they are sold at stores that carry other products and is not a CBD-based store.

For Garrambone, though, the direction of travel is clear and the cannabis industry’s growth will continue to force progress. “Everyone is going to wake up,” he says. “They are going to realise all the money that’s in it. Cannabis is a gold mine.”

Additional reporting by Joe Rennison in New York