The Best Hellraiser Movies, Ranked

Photo: Murray Close/Getty Images

When Clive Barker made his directorial debut by adapting his 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart into 1987’s Hellraiser, there’s no way he could have realized what he was unleashing. Much like the characters in the movie, Barker opened up a world of horrors — mainly of the low-budget, straight-to-video variety.

The original Hellraiser remains the purest onscreen representation of Barker’s twisted imagination. Over the course of more than 30 years, that purity has been gradually diluted and defiled. Barker’s unique creation of the hedonistic hell spawn called Cenobites, summoned by a mysterious puzzle box known as the Lament Configuration, became fodder for an increasingly disreputable horror franchise.

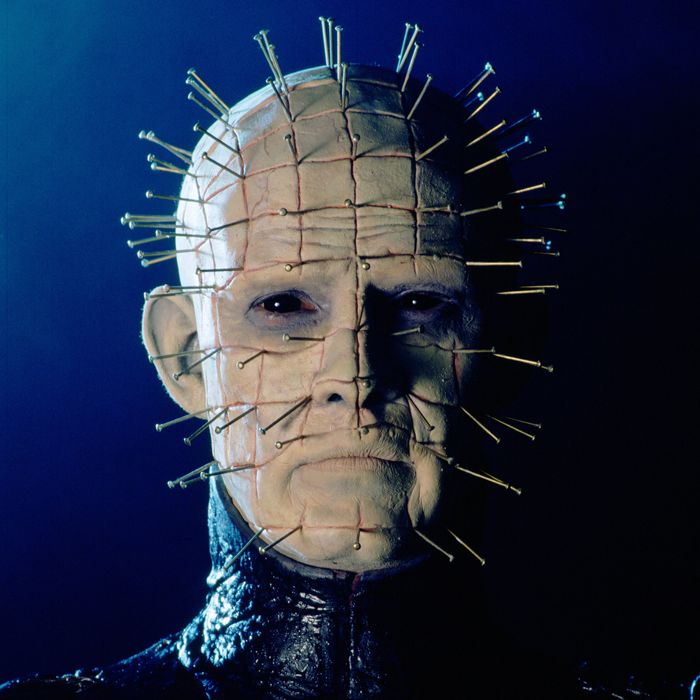

That singular artistic vision, steeped in BDSM and deviant sexuality, found itself pared down to just Doug Bradley’s prickly Cenobite villain, later nicknamed Pinhead, as he terrorizes an assortment of hapless protagonists. In many of the later movies, thrown together from unrelated screenplays and sometimes produced solely for the purpose of retaining licensing rights, Pinhead and the Lament Configuration are reduced to little more than cameos.

The series iconography has remained indelible even as the movies have become increasingly obscure. The original designs for Pinhead and the Lament Configuration retain their striking, otherworldly qualities no matter the context, and their mere appearances in later movies serve as placeholders for scares that aren’t always present. Although the other Cenobites usually change from film to film, they too offer reliably unsettling imagery in movies that often fall short in other ways.

With a high-profile new installment (titled simply Hellraiser), produced by Barker and directed by The Night House’s David Bruckner, now streaming on Hulu, it’s the perfect time to assess the entire sprawling franchise. As Pinhead says, “We have such sights to show you” — even if some aren’t exactly worth seeing.

Nothing screams “horror classic” quite like “contractual obligation.” That’s the sole reason for the existence of the ninth Hellraiser movie, which was produced quickly and cheaply so that Dimension Films’ franchise rights wouldn’t revert back to Barker. Even Bradley couldn’t be bothered to show up, so Pinhead is played by the shambling, surprisingly soft-spoken Stephan Smith Collins. He’s summoned by a pair of douchebros on a bender in Tijuana, one of whom scoffs, “What, like bondage and shit?” when offered the exquisite torture of the Cenobites. Most of the movie takes place in an isolated house where the two friends’ families have gathered to discuss their disappearance, when one of them unexpectedly returns, pursued by Pinhead. The dialogue, acting, and echo-filled sound design are all abysmal, one character looks up “Cenobite” in the dictionary, and there’s a scene of incestuous flirting that involves sexy soup-slurping.

Bradley makes his final onscreen appearance as Pinhead in director Rick Bota’s third Hellraiser movie. It’s a stretch to even call this a Hellraiser movie, since it takes place in the “real” world, where Pinhead, the Lament Configuration, and the Cenobites are pop-culture figures appearing in the popular video game Hellworld. There’s some potential for a clever meta take on the franchise, similar to Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, but the movie is more concerned with cheesy kill scenes than saying anything interesting. Here a shady benefactor (Lance Henriksen) throws a Hellworld party to lure in a group of unsuspecting friends. At this video-game party where no one plays any video games, Pinhead plays the role of a generic slasher, offing the attractive, horny young people one by one. He’s just a tool being used by the actual villain in a dull, unconvincing revenge scheme. At least a pre-fame Henry Cavill gets to hit on a fellow party guest by saying, “I’d love to see your puzzle box.”

It’s sort of endearing that longtime special-effects designer Gary J. Tunnicliffe, who’d been with the franchise since the third movie, finally got his chance to write and direct, even if this tenth Hellraiser installment was yet another desperate gambit for Dimension to hold on to the film rights. Tunnicliffe finds a better replacement Pinhead in Paul T. Taylor, who captures more of Bradley’s menacing grandeur. The main story is a slog, a warmed-over Seven-style mystery about a serial killer who models his murders after the Ten Commandments, but Tunnicliffe has bigger ambitions as well, expanding on the Cenobites’ theological implications and bringing in other celestial beings. Those ambitions are mostly thwarted by the budget and the uninspired central story line. Still, befitting a movie directed by a special-effects artist, the creature design is impressive, whether or not those creatures are doing anything interesting.

Bota’s second Hellraiser movie was shot back-to-back with Hellworld in Romania, and the two were released three months apart in 2005. Despite their simultaneous production, they have almost nothing in common; Deader is a more serious examination of guilt and mortality, with some semi-intriguing ideas about Pinhead and the Cenobites, when they finally show up. B-movie veteran and former MTV VJ Kari Wuhrer is the movie’s biggest liability, grossly miscast as hard-boiled, chain-smoking reporter Amy Klein, who writes edgy articles with headlines like “How to Be a Crack Whore.” Wuhrer can’t convey Amy’s emotional anguish as she immerses herself in the cult of the “Deaders,” who seem to be able to kill people and then bring them back to life. Amy’s life unravels in the thrall of cult leader Winter (Paul Rhys), but neither Wuhrer nor Bota can make her descent into madness a coherent or satisfying journey. It has its creepy moments along the way, though.

Beginning the trend of Hellraiser sequels repurposed from existing screenplays, the fifth movie in the franchise is adapted from a spec script by Paul Harris Boardman and future Doctor Strange and The Black Phone filmmaker Scott Derrickson, who also directs. There are flashes of Derrickson’s forthcoming command of genre and style, but Inferno, the first Hellraiser movie to be released direct to video, doesn’t allow him much room for experimentation. It establishes the policy of reducing Pinhead to a handful of brief appearances, instead focusing on a corrupt police detective (Craig Sheffer) who’s tracking a serial killer. Or is he? As the detective’s reality falls apart, Sheffer delivers an overwrought performance that makes the supposedly serious revelations laughable. Pinhead eventually arrives to impart a life lesson in the vein of A Christmas Carol or It’s a Wonderful Life, only with eternal torment in place of a second chance to get things right.

The plot of the sixth Hellraiser movie (Bota’s first as director) is remarkably similar to the plot of Inferno, with another morally compromised man (Dean Winters’s Trevor Gooden) losing his grip on reality as he attempts to solve a murder mystery connected to the puzzle box. Hellseeker gets extra points for being the only later sequel to bring back an original character aside from Pinhead with Ashley Laurence reprising her role as Kirsty Cotton from the first two movies. Now married to Trevor, Kirsty seems to die in a car accident at the beginning of the movie, but Trevor is haunted by her presence. Most of Hellseeker has little to do with the prior series’ mythology, but Bota got an uncredited assist from Barker to create a finale that offers a somewhat satisfying resolution to the conflict between Kirsty and Pinhead. It’s a meager payoff, but that may be the best these sequels have to offer.

By the third movie, Hellraiser had become a victim of its own success, no longer able to contain itself to Barker’s sick little niche. Pinhead, who had more of a supporting role in the first two movies, is now front and center, eager to escape from hell and wreak havoc on the outside world. Like previous horror bit players, including Jason Voorhees and Leatherface, he’s a breakout star about to be overexposed. Pinhead becomes an over-the-top villain who spouts one-liners and turns his victims into ridiculous new Cenobites, including a DJ Cenobite who fires razor-sharp CDs and a cameraman Cenobite with a telephoto lens for an eye. TV reporter Joey Summerskill (Terry Farrell) is the only one who can stop him by forcing him to face his former human existence. The expansion of the backstory is awkward, and Pinhead is a poor fit for a larger production with lots of explosions. It’s silly but mostly harmless and sometimes fun, and it features the first onscreen instance of someone using the word “Pinhead” (which Barker hated).

Although there are unofficial fan reconstructions floating around online, it’s impossible to say what director Kevin Yagher’s true vision for the fourth Hellraiser movie would have looked like. If Hell on Earth was the series’ effort to go mainstream, then Bloodline is its effort to become a full-on epic, taking place in three different time periods spanning centuries. On a space station in 2127, a descendant of the puzzle box’s original creator tells the story of his family legacy as he prepares a trap to finally destroy Pinhead. Bruce Ramsay plays three members of the LeMarchand family in 18th-century France, in 1996 New York, and in 2127. Studio executives rejected Yagher’s more expansive take on the material, bringing in another director for reshoots so extensive that he removed his name from the project and is credited by the infamous pseudonym Alan Smithee. Even in its compromised form, though, Bloodline is gloriously absurd, a bombastic, grandiose saga that makes Pinhead almost believable as a galaxy-level threat.

Bruckner brings a level of professionalism and thoughtfulness to this reboot that had been missing from the franchise for at least two decades, along with higher production levels to match. Sense8’s Jamie Clayton proves herself a worthy successor to Bradley as the new Pinhead, making the role her own rather than struggling in Bradley’s shadow like Collins and Taylor. Yet the plot is only a slight improvement over many of the earlier, cheaper entries, once again telling a largely unrelated story with some Cenobite involvement. Odessa A’zion plays a recovering drug addict who happens upon the puzzle box, here given a slight makeover with multiple new configurations. The acting is impressive, and the new Cenobite designs are appealingly grotesque, but the somber, downbeat tone of contemporary horror doesn’t quite fit with Barker’s salacious fantasies. It’s the best Hellraiser movie since the first two, but it isn’t as much of a reinvigoration as it could have been.

Without the later burdens of franchise expectations, in his original adaptation Barker is free to tell his particular story of sexual obsession that transcends death, with the Cenobites mostly as background players in the drama among the depraved Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman), his brother, Larry (Andrew Robinson), and Larry’s wife, Julia (Clare Higgins). Frank opens the puzzle box and summons the Cenobites, rendering himself a skinless corpse who needs blood to become whole again. He manipulates Julia into procuring him victims and is only stopped when Larry’s daughter Kirsty (Ashley Laurence) discovers the truth. As a first-time director, Barker doesn’t always have a full handle on the material, and the acting is often stiff. Barker compensates with delightfully goopy practical effects, freely mixing gore and sexuality. It’s messy in every sense, but it’s a fascinating glimpse into Barker’s own depraved mind.

What’s so great about the second Hellraiser movie is that it retains most of Barker’s sexual deviance while expanding the scope and engaging in some effective world-building. The Cenobites come into their own, and Bradley gives Pinhead the bearing of a nascent horror icon. Laurence and Higgins give much stronger performances than they did in the first movie, as both of their characters return with more forceful screen presences. No longer subservient to Frank, Julia is now a fully realized and wonderfully nasty villain herself. Kirsty is more assertive, as she recovers from Post-Final-Girl Stress Disorder in a mental institution and then follows Julia and the sadistic psychiatrist Dr. Channard (Kenneth Cranham) into literal hell. Nearly the entire second half takes place in hell itself, which director Tony Randel (an editor on the first movie) depicts as an M.C. Escher–style labyrinth. The plot doesn’t always make sense, but Hellbound is a mesmerizing, hallucinatory nightmare with ornate production design and beautifully disgusting gore. It’s everything that Barker envisioned in the first movie but bigger and more intense.