Life can be different: 10 years ago, Occupy Wall Street changed the world | Occupy movement

I sprinted down 7th Avenue, down 6th Avenue, across Canal Street. Trucks and cars stood still as the bodies flooding the street halted their movement. People walked out of stores to cheer. Children pressed their faces to backseat windows while parents held up peace signs from the front.

Minutes earlier, I’d been standing in a crowd in New York City’s Union Square. Then the running had commenced, outpacing the police as we took the streets on our way to join another march.

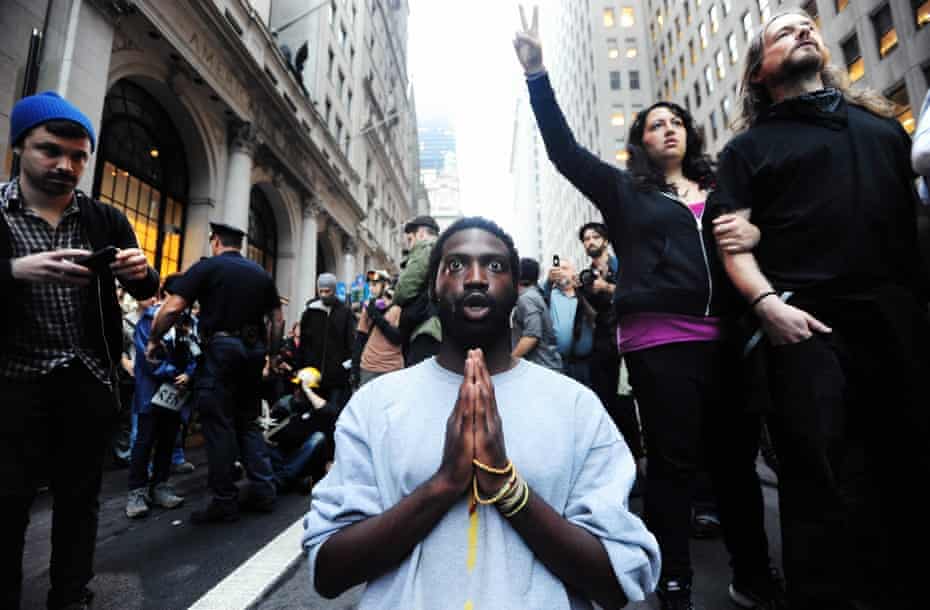

It was 17 November 2011, and Occupy Wall Street was two months old. Three days earlier, the New York police department had raided Zuccotti park, home to the movement’s encampment. They’d used brute force to tear apart a peaceful protest and ruined thousands of books, but their pepper spray and riot gear were not enough to destroy the energy housed inside the park. “You can’t evict an idea whose time has come,” read many protest signs.

That was 10 years ago.

Occupy Wall Street politicized an entire generation – one that grew up under George W Bush in the post-9/11 years, pinning all their hopes on Barack Obama. Let down when his message of “hope and change” failed to manifest after the 2008 global financial crisis, they began to question American political and economic institutions themselves.

I was one of those millennials.

The movement upended my life, introducing me to new politics and people. It also upended the world, part of a string of uprisings that spread from Tunisia and Egypt to Spain and Chile to, finally, the United States.

Occupy’s rise in 2011 marked the re-entry of class consciousness into mainstream American politics. Occupy had two pillars: its critique of inequality, and its vision of an alternative way of organizing society. The former moved from the fringe to the center, bringing inequality into the national discourse; the latter has been largely overlooked. The movement made decisions by consensus, which was messy and slow, but it also challenged the idea that the way we live is a given.

That’s what made Occupy stand out to Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s most prominent public intellectuals, who has spoken extensively about the movement.

“Occupy was different than other movements,” he told me, comparing it to the civil rights and anti-war movements. “By its nature, as a tactic, it brought people together to construct a community … It was an educational experience, which for many people changed the way they think of what life could be.”

Ten years on, the enduring influence of Occupy on its participants and national politics serves as a reminder that movements are not as fleeting as they may appear – and not just a phase young people pass through on the way to their real lives.

I grew up in the affluent, liberal suburbs of New Jersey, about fifteen miles west of Manhattan. My mom is the director of a small museum; my dad, a professor at a public university. As a teenager, my grasp on politics boiled down to Republicans versus Democrats. I couldn’t have told you what “anticapitalist” meant, but I was interested in gender politics and innately skeptical of those in power.

In early 2011, as the Arab spring was blooming, I was in my first year at NYU. I quickly befriended another student already immersed in radical politics and went to my first protest.

That summer, the Canadian magazine Adbusters put out a call to “#OccupyWallStreet,” with a poster depicting a ballerina balanced atop the financial district’s charging bull statue. I was about to start an internship at the Village Voice, where I’d be writing for the alt-weekly’s website. My friend put me in touch with someone organizing the protest and I interviewed him for the paper.

Kalle Lasn, the editor in chief of Adbusters, had been politicized in 1968. “All of a sudden, 50 years later, another opportunity came to pull off some sort of global transformation,” he says now. “That is the legacy of Occupy Wall Street.”

On 17 September, I covered Occupy for the Voice. The protest landed at a one-block-wide by one-block-long plaza called Zuccotti park. The organizers’ first-choice location hadn’t panned out, and Zuccotti had been on a list of backups. It was a privately owned public space, not subject to the closing time enforced at the city’s parks. That night, friends and strangers gathered, passing around someone’s old guitar as police officers looked on in boredom. The mood was playful and buoyant – but when I got up to walk home around 3am, most people stayed.

One week later, protesters were still occupying Zuccotti. Operating without leaders or demands, they quickly created working groups to handle the tasks necessary to organize and feed a large group of people, and began to hold regular general assemblies. But during a march on 25 September, officers kettled and pepper sprayed a group of young women. Video of the incident went viral; the movement grew dramatically. The next week, the NYPD arrested more than 700 people on a march across the Brooklyn Bridge.

By then, I was captivated by the energy I kept encountering in the city’s streets. Occupy’s critique of inequality and capitalism, its chants of “We are the 99%,” its modeling of a leaderless democratic society all resonated deeply with participants.

“We are the 99%,” a slogan often attributed, at least in part, to the lateanthropologist David Graeber, succinctly underscored Occupy’s point about inequality: that a tiny minority of the population – the top 1% – controlled the majority of wealth in the United States. The slogan was building solidarity, suggesting the middle and upper-middle classes had more in common with the working class than with the wealthy elite.

‘This is the world I want to live in’

Nelini Stamp always imagined she’d end up on Broadway. An Afro-Latina raised in New York City, she studied at the city’s famed LaGuardia high school of music & art and performing rts.

Instead, she dropped out of high school when she realized she couldn’t afford college. She worked retail jobs; she tried domestic work. When the minimum wage increased in 2005, she learned that the Working Families party, a progressive grassroots political party, had helped make it happen. Then, the financial crash happened.

“My family went underwater in a lot of different ways. And I saw that hope and change message [from Obama] and I was like, I want some of that! Give me some of that – like many people did with Obama,” she recounted. She remembered the WFP and started canvassing: by summer 2011 Stamp was WFP’s political director in Westchester and Putnam counties, just north of the city.

On 17 September she stopped by Zuccotti. Seeing everybody sharing their stories hooked her.

“This is the world I want to live in, where people are not afraid to say the struggles and the hard times that they had,” Stamp thought. “Because I was afraid. At that point, I hadn’t really told many people that I dropped out of high school. I thought it was going to be looked down upon.”

That conversation space was one of Occupy’s defining traits.

Rebecca Solnit, an author and activist involved with Occupy in California, reminisced on the changes brought by the movement. “Part of what I thought was incredibly exciting was a deep, real conversation among people in an era where part of what capitalism, neoliberalism, financial desperation were doing to people was isolating us,” she told me. “Occupy immediately taught me that, oh yeah, when you lose your job, you stay home. When you lose your home, you disappear from the neighborhood. When you’re overwhelmed by medical debt or unable to have medical care, you may suffer invisibly. And the sheer visibility of all that suffering was being made visible by those conversations. I found it felt like a great awakening.”

Consensus decision-making, twinkling fingers – up for approval, down for disapproval, straight ahead for lukewarm – used to silently express opinions while someone else spoke: it was all new to Stamp, who came from the structured world of electoral politics. But when the assembly split into working groups and someone mentioned outreach, she leapt up. “I was like, That is what I know how to do. I don’t know what any of y’all are talking about. Direct action, I don’t know how to do that.”

She started keeping a sleeping bag under her desk at work; she used the office printers to make Occupy flyers. Some mornings, she’d run into a nearby Sephora to freshen up. Others, she’d head to her apartment to shower, just to return to sleep outside again that night.

She considered quitting her job, but WFP backed her movement-building work. “They were like, This is an important movement for class politics in our country and we’re going to support our staff who are out there by still paying them … And that was a level of trust.”

There were also, of course, some negatives. Occupy prioritized economic justice and overlooked nuances in an effort to build solidarity among “the 99%”.

“Everybody in the world is talking about how white Occupy was, and so when I was asked to be a facilitator almost every other night, to the point where my voice was being lost and people would bring me tea, I was like, why is this happening? And it clicked in my head: Oh, Black woman,” she said. “There were a few of us Black folks who were just consistently put up there to facilitate. And yes, I didn’t want Black and brown people erased in the movement, and also I didn’t want to be used.”

“Honestly,” she continued, “you recreate a world, you’re going to get the best parts of it and the worst parts of it.”

In February 2012, a NYPD officer killed Ramarley Graham, an unarmed Black 18-year-old man; weeks later, George Zimmerman killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida. Stamp began organizing around racial justice. She co-founded Dream Defenders, a group that organizes youth in Florida. She also co-founded Occupy Our Homes, which occupied homes to prevent foreclosures. She is now WFP’s director of strategy and partnerships.

As Black Lives Matter protests filled the streets in summer 2020, amid a pandemic that has disproportionately affected communities of color, Stamp used the skills she acquired in Zuccotti for a movement that centered the issues Occupy had skirted around. There was a campaign to cut $1bn from the NYPD budget, and she helped organize an occupation in front of City Hall with people she’d met in 2011.

From skepticism to a career in organizing

For Stamp, it has been a decade of nonstop momentum since Occupy, but she is far from alone in experiencing the movement’s lingering legacy. “[Occupy] was an almost immeasurably impactful phenomenon,” Solnit told me. “Like a stone thrown into a pond, the ripples keep spreading outwards.”

Tamara Shapiro had just returned to New York in September 2011. She grew up near Washington DC, where she participated in a program that brings together Black and Jewish high school students to confront racism and antisemitism.

She organized around Israel/Palestine, first in college in Wisconsin and then in Brooklyn. But in 2010, at age 28, she quit, burnt out from the loneliness of that work. She nannied and traveled abroad. Once back in New York, she took an internship with two film-makers.

During the occupation’s first week, she went to scope out Zuccotti. She had trouble taking it seriously. “I had a lot of skepticism because I had come from more traditional organizing. So I was like, What’s the goal? Who’s behind this?” she remembered. “I can’t really join something if I don’t understand who’s putting it forward.”

But she knew someone from Occupy who was workingto connect the many Occupy encampments quickly spreading around the country. Within a month, more than 600 communities in the US, as well as many cities abroad, had organized protests.

The working group, which became known as InterOccupy, rapidly engulfed Shapiro, and she became busy facilitating calls between occupations in various cities.

In October 2012, she went on a retreat where occupiers debriefed on the past year. They rushed home because they heard a storm was coming. When Hurricane Sandy hit New York, organizers quickly formed Occupy Sandy, a disaster relief mutual aid group. The experience deepened the friendships Shapiro had made through Occupy.

Soon after, Shapiro started a part-time job at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies, and co-founded Movement Netlab, which investigates how decentralized networks like Occupy best function. She helped start IfNotNow, a movement aiming to end the American Jewish community’s support for Israel’s occupation of Palestine. She had moved further to the left since quitting her work on Palestine in 2010, and she felt the left had become more accepting. She sensed more energy for direct action among young Jews. She was also heavily involved with organizing projects that came out of Occupy Sandy in the Rockaways, one of the hardest-hit neighborhoods.

She now works full-time at the New York City Network of Worker Cooperatives. I ask when she realized organizing had become her career. “Yesterday?” she replied, half-jokingly.

“Can it be a career? Absolutely. Do I think it is the right career for me?” she asked. “As a white person, I don’t know if I should be paid to do the kind of organizing work I have been doing. I really think it should be people of color leading,” she says. Now she is left asking herself how to be most useful. “I don’t know the answer to those questions. It’s what I’m grappling with today.”

Occupy was ‘an accelerator’

The lives of many people who frequented Zuccotti Park continue to intersect, a growing web of organizers who call on one another when moments for action arise or run into each other at protests and parties. Bonds forged in those heady months of fall 2011 still endure.

Born in Panama and raised on military bases around the globe, Sandy Nurse never felt as if she had a home town. But in 2009, at age 25, she arrived in New York City, the closest thing to a home town she could find. Decades earlier, her dad had come to the US via Mexico, 17 years old and undocumented, before making his way to New York and joining the military to become a citizen.

Nurse enrolled in a master’s program in international affairs at the New School in New York, but she took a hiatus in early 2011 to work with the United Nations World Food Programme in Haiti for three months. “A handful of things I experienced really exposed the flaws in these larger top-down global institutions, and how they’re delivering aid and perpetuating chronic issues,” she said.

She went to Occupy’s general assembly on 17 September. She’d never organized a direct action, but it sounded fun. She was a natural, quickly becoming engrossed in the logistics of organizing actions.

Nurse wanted to do something other than observe and write about conflict. “I wanted to be a part of physically dissenting in some way,” she told me. “I just needed to put my body into a motion that was not from an objective point of view, but very much the personal. I just needed to get some rage out in some way. I was outraged.”

She realized early on that she would not be returning to the New School. Whatever she did now, she wouldn’t need a piece of paper to prove her qualifications, she figured. Plus, she had a lot of student debt. Occupy’s legacy includes mainstreaming the ideas of free public higher education and forgiving student debt – policies championed by Bernie Sanders in his presidential campaigns, which themselves relied on the class consciousness that Occupy helped build.

Zuccotti felt essential to Nurse. “The relationships I developed in that space, in a short period of time, have completely transformed my life, my perception of what deep friendship can be, and what a loving chosen family can be,” she said. She went on to co-found Mayday Space, an organizing hub for movements; started a compost pickup service called BK ROT; and trained as a carpenter. In 2020, she helped organize the City Hall occupation with Stamp.

This summer, Nurse won the Democratic primary for city council in her Brooklyn district. Local government has access to resources, she realized: there are only so many times you can take out the bolt cutters to access a space and then get booted out before you wonder what needs to happen to keep it open. When she put out a call on Facebook for a masseuse to aid her campaign staff, their bodies wrecked from long hours knocking on doors, it was Shapiro who answered, saying that her partner was a masseuse. Nurse hired him.

“For some people, Occupy was everything – and it was really momentous – but to me, I don’t feel like Occupy has totally defined me,” Nurse told me. “But it was an accelerator. It was a concentrated amount of people in a space that allowed for ideas and co-creation … [it gave me confidence] that where I was going, there were many, many, many people pulling in that direction.”

One morning this past summer, I rode my bike to Zuccotti park. NYPD barricades were grouped together on the east side. On the south side, street vendors sold falafel and smoothies. Construction workers gathered on the west side. About two dozen people sat scattered on the park’s benches. I searched for a trace of Occupy, but found only well-maintained stone slabs and floor lights, perfectly spaced trees and flower beds.

Today, OWS is the networks and campaigns and political shifts it generated. It is the people and work and experiences to which it led thousands, catching so many of us in the right time and place to have our lives upended, altering trajectories or cementing those already in progress.

“It did put inequality on the national agenda, and it stayed there,” Chomsky said, citing Sanders’s presidential runs, the success of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the strength of the climate justice movement as part of that legacy. “But it was much more than that. You probably felt it in your own life, but for the actual participants, it was participation in a community for the first time in their lives. We’re a very atomized society. People are separated from one another.”

But with Occupy, he continued, “You had people getting together, learning that they can work together. They can work in a participatory community. They can set up their own food supplies. They can have meetings where things can be discussed. Life can be different. There are different forms of existence than just individual subordination to a master in a gig economy. That’s important, and it’s turned lots of people into activists and given them a vision of a future that’s on a human scale.”

Occupy wasn’t even supposed to be here, I thought, as I looked around Zuccotti. But for two months in 2011, this tiny park modeled the beauty and the mess of trying to reorganize society on different terms, and that, in turn, pushed many to continue searching for new possibilities in the ways we live, work, eat and engage in the world.

The space was secondary, and then essential, and then gone.