Fox News anchor Chris Wallace: ‘There’s no spin to truth’

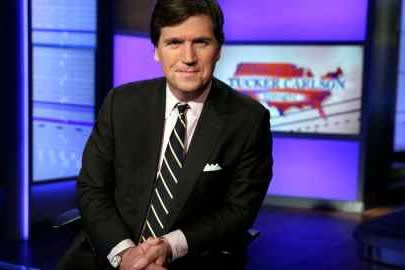

Chris Wallace defies simple characterisation. He works for Fox News, the Rupert Murdoch-controlled channel beloved by the conservative half of America, the one that features some of its loudest and most belligerent voices. Just think of the primetime Fox host Tucker Carlson, who recently railed against mandatory vaccines in the US military as a plot to identify “Christians . . . free thinkers, the men with high testosterone levels and anyone else who doesn’t love Joe Biden”.

Wallace is cut from different cloth. For starters, he’s a journalist and not a ranting commentator, anchoring the weekend show Fox News Sunday for the past 18 years. He is known for putting tough questions to politicians whatever their political stripe. He once asked Vladimir Putin why so many people close to him “end up dead” and, in a memorable pre-election interview with Donald Trump last year, took the then president to task after he boasted about having “aced” a test of his cognitive abilities. Wallace, who had taken the same test, remarked to Trump in the interview that it was not the toughest assessment: “They have a picture and it says ‘what’s that?’ And it’s an elephant.”

Today Wallace is the one taking the questions in Bistro Bis on Capitol Hill, across the street from his Fox News studio. I am keen to hear how the channel is faring with a Democrat in the White House. Drawing on decades in the Washington firmament, Wallace also has written a book: Countdown bin Laden, about the mission to find and kill the al-Qaeda leader. We were supposed to meet for lunch but my arrival in DC was delayed by a train mishap in New York that led to me taking an unexpected detour north-east into deepest Connecticut. Rather than have a truncated bite, Wallace has agreed to meet later for drinks instead.

“I hear you were heading to Boston,” he says wryly, as he takes his seat across from me in the bar. It would normally be bustling with gossiping politicos but Washington is still not quite back to pre-pandemic normality and on this humid late autumn afternoon we are the only ones here.

He puts on a pair of owlish spectacles and studies the menu, signalling for the waiter and choosing a glass of Pinot Gris. With its wood-panelled walls and a long bar that must have been the scene of thousands of whispered conversations between Washington power brokers, Bistro Bis feels like a place that requires a more substantial drink. I go for a vodka martini.

We are meeting in the month before the Biden administration finally got the votes needed for its $1.2tn infrastructure bill, a tortured process that exposed deep divisions between the progressive and moderate wings of the Democratic party. But progress has been glacial on Biden’s other signature piece of legislation, the so-called Build Back Better programme, which will reinforce the social security safety net with free pre-school education and other initiatives.

“I don’t think this administration and this president have their act together,” Wallace says flatly, pointing to the chaos of the summer’s botched US withdrawal from Afghanistan. “They started off strong and they passed the Covid relief bill” but in the summer “it’s like the wind died”.

I wonder if, like other political reporters, he secretly pines for the mania and chaos of the Trump administration. “You’re always rooting for a good story but you want good things to happen as well. The Trump administration, I think, totally mishandled the pandemic and getting people to wear masks and getting people to take it seriously . . . Do I long for that just because it’s exciting? No.”

I want to know more about the pandemic, which remains the dominant faultline in American politics, and Wallace mentions Greg Abbott, the governor of Texas, describing him as a “good, sensible guy”. Abbott recently barred companies receiving public funds from imposing mask or vaccine mandates, threatening to fine them if they did.

“It’s one thing to say, ‘I’m not, as the governor of the state, going to impose a mandate,’” says Wallace. “But to say to American Airlines, which is based in Texas, ‘You are prohibited from imposing a vaccine mandate’ . . . I find that astonishing, particularly for Republicans who tend to say the government should step back and let private individuals or private companies decide.”

Abbott has been mentioned as a possible Republican presidential candidate in 2024. How “good” or “sensible” can he be if he is playing politics with a deadly virus as Wallace describes? “I certainly don’t agree with what he’s doing here. I guess what I’m saying is sometimes I think people know better and sometimes I think they don’t. And I think Greg Abbott knows better.”

Bistro Bis

15 E St NW, Washington, DC, 20001

Glass of Pinot Gris

Vodka martini

Total (including tip) $37.35

Our drinks have arrived. There is an olive bobbing pleasingly in the martini and a thin layer of condensation around the chilled glass. The first sip does wonders for my jet lag.

Wallace has been a journalist for 52 years. He started at The Boston Globe fresh out of Harvard and then moved into television with long stints at NBC News and ABC News before joining Fox in 2003. His industry has changed in that time: these days, he says, people approach him in public and thank him for being fair. “While I like being praised as much as the next person, I actually find it very sad. When I started at The Globe in 1969, being fair wasn’t something you got praised for, it was what kept you from being fired. I think it’s an accurate but sad commentary on the news business.”

He is referring, of course, to America’s polarised media and political landscape. Critics of Fox News — and there are plenty — blame the network for widening the divide in US politics. The channel was also a favourite of Trump’s when the then president wasn’t having a tantrum about an “unfair” poll or lashing out at Wallace. Trump would regularly call in to particular Fox programmes; Sean Hannity, who, like Tucker Carlson, hosts an evening opinion show on the network, even appeared on stage at a Trump rally before the 2018 midterms.

Much of what Fox opinion hosts said in that period was repeated back by Trump, I say. “An echo chamber,” says Wallace. But do hosts such as Carlson and Hannity make the political weather in America or do they reflect it?

He deflects, pointing to MSNBC and CNN, which he says also have evening opinion programming — albeit from a different political perspective — with “that same kind of feedback loop”. None of the channels would be “expressing these opinions if there weren’t a market for it”, he says. He is right but I find it puzzling that he does not seem to link Fox’s role in driving this trend with the dearth of fairness in journalism that he laments.

He has, in the past, defended Fox’s mix of news and conservative opinion programming, comparing the network to a typical US newspaper, where news and opinion sections are clearly delineated. But opinion has become quite a loose term at Fox these days. Carlson’s new documentary series Patriot Purge makes the absurd suggestion that the January 6 attack on the US Capitol building by raging Trump supporters might have been a “false flag” attack — secretly carried out by US authorities intent on discrediting a band of true American patriots.

Certain Fox hosts are prone to send liberal America into apoplexy but the network’s mix of news and incendiary commentary has propelled its ratings and profits. Its financial success is one of the reasons why Murdoch kept the network in 2017 after selling his entertainment businesses to Disney.

Murdoch’s love of news was another reason to keep the channel, which last month had its 25th anniversary. “The thing that’s most interesting when I’ve sat down with Rupert is he’s a newsman,” Wallace says. “He doesn’t want to talk about how we are going to build an audience. He wants to know what’s happening, what’s going on at the White House.”

He pays credit to Murdoch and his son Lachlan, now chief executive of the company that owns Fox News, for investing in the channel. “The fact is that the Murdochs spent millions of dollars completely redoing the newsroom in New York and Washington. If all you wanted was opinion you don’t need all those reporters and producers and associate producers and desk assistants.” The Murdochs, he says, put “their money where their mouth is when it comes to journalism”.

I ask Wallace about the book. It is an old fashioned “tick-tock” narrative, detailing the events leading up to the bin Laden mission. Wallace interviewed many of the players involved, including former CIA chief Leon Panetta, William McRaven, the former head of the US Special Operations Command, who planned the raid, and Hillary Clinton, then the US secretary of state.

It’s the second book in his Countdown series — his first, on Harry Truman and the production of the atomic bomb, was a research and writing experience that he says made him frustrated “that I was working off ploughed ground”, given the lack of contemporary sources. With the bin Laden operation, he recalls the famous picture of an anxious Barack Obama, Biden and Clinton with their security advisers watching the mission unfold from the White House Situation Room. The American protagonists in the story are all still around. “I thought: I know most of these people. I’m going to be able to talk to most of them,” he says.

He knows them because he has been a Washington fixture for so long, a journalist who, as a child, always seemed destined for a career in news. His father, the late Mike Wallace, was a huge figure in American journalism, a CBS correspondent and one of the first hosts of the venerated news programme 60 Minutes. His parents divorced when Wallace was a year old and, although his father would play a larger role in his life later, as a child “we didn’t have much of a relationship”.

A bigger influence in his early years was his stepfather, Bill Leonard, who would become head of the CBS election unit: he got the younger Wallace a job in the anchor’s booth as Walter Cronkite’s “gofer” (“I’d go for coffee, go for pencils”) at the 1964 Republican convention in San Francisco.

His early proximity to figures at the top of broadcast journalism led to other significant moments in his life. Nancy Cronkite, the anchor’s eldest daughter, was Wallace’s first girlfriend. While in high school he met Malcolm X thanks to an introduction from his own father. The elder Wallace had formed a friendship with the civil rights leader and after the broadcaster died in 2012 there was a memorial service for him in New York where Wallace met Attallah Shabazz, Malcolm’s daughter.

“Shortly before Malcolm was assassinated [in 1965], he and my father had had a conversation. Malcolm had said, ‘Look, if anything happens to me I’d like you to look out for my family.’” Wallace says he was “absolutely unaware” of this arrangement until his father’s death; he and Attallah then became friends. “She sends me notes as ‘Your Sister’, and I send her notes as ‘Your Brother’,” he reveals. “And when she comes to Washington, I take her out.”

Wallace’s even-handed approach to his interviews earned him two gigs moderating US presidential debates. The first, in 2016, between Clinton and Trump (who has accused Wallace of being “controlled by the radical left”), was relatively civil; the second, last year, between Biden and Trump, was a relentless shouting match that came close to a punch-up.

We have almost finished our drinks. I have one more question for Wallace and it relates to last year’s debate. The White House revealed shortly afterwards that Trump and his wife had tested positive for coronavirus. Wallace reported that the president and members of his family had taken off masks once inside the auditorium in Cleveland, breaching the rules of the debate. An angry Wallace took to the Fox airwaves. “Wear the damn mask,” he told viewers. “Follow the science. If I could say one thing to all of the people out there watching: forget the politics. This is a public safety health issue.”

Fast forward to April this year and Carlson addressed his audience on Fox with a different message, telling viewers to confront anyone they spotted wearing a mask outdoors and to “call the police immediately” if they saw a mask-wearing child, which, he said, was “child abuse”.

Carlson, who has also cast doubt over the efficacy of vaccines, is watched by millions of people. Given Wallace’s own stated views about the importance of mask-wearing and following the science, what does he think of his colleague’s comments?

He smiles for a second. “Well, I’d say a couple of things. This is a public health crisis and it needs to be taken very seriously.” He then tells me about an encounter he had covering Ronald Reagan’s first presidential campaign in 1980. He was chasing a story about a controversy at the time — he can’t remember what, only that “something ticklish was going on”. William Casey, who would go on to become director of the CIA, chaired the Reagan campaign; notepad in hand, Wallace approached Casey to ask him the question about the controversy. Casey, he says, “looked at me and he said, ‘Why on earth would I answer that question?’

“Fox News has employed me for 18 years,” he continues. “They’ve never interfered with a question, with a guest I’ve brought on or a question I’ve asked. They have changed my life. They’ve changed my career. So to paraphrase William Casey, why on earth would I share any concerns I have about Fox News with the readers of the Financial Times?”

At that moment his phone rings; it is his son, daughter-in-law and grandson on a video call. He says hello and introduces me. When he has ended the call I tell him I’m going to have another crack.

“You won’t annoy me,” he says. “But you won’t get anywhere.” I try anyway: Carlson is incredibly popular. What about the people who might follow his advice?

He won’t refer to Carlson. “I am only responsible for and only have control over my piece of real estate,” he says. “I’m proud of what we do . . . I feel a tremendous sense of responsibility to my audience and to the truth.” Truth, he says, “is non-negotiable. There’s no spin to truth. Truth is truth.”

We get up to leave and he tells me he will soon be heading to the UK: this Tuesday he will take questions at the Oxford Union. There, the students will encounter an expert in the art of interviewing and a broadcaster who will remain stoutly loyal in public to his colleagues — however objectionable their views may be.

Matthew Garrahan is the FT’s news editor

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

More on the US media . . .

US TV network ratings dive after prime years of Trump and trauma

Audiences have deserted media groups in droves as the news cycle has eased

Opinion: The rise and rise of Tucker Carlson conservatism

Fox News’s most popular anchor may be aiming for the Republican presidential nomination, says Edward Luce