Did Occupy Wall Street mean anything at all?

Around noon on September 24 2011, a young black man named Robert Stephens fell to his knees in the middle of the road outside Chase Bank headquarters on Liberty Street, New York City. Wearing a white fleece and black-rimmed glasses, Stephens pointed at the Chase building and wailed: “That’s the bank that took my parents’ home.”

Like so many in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, his family had lost their house to the bank. As Stephens continued to scream from the pavement, police officers circled. “I’m not moving. I’m not gonna be quiet!” His voice was growing hoarse. Tears ran down his face.

That morning, Stephens had joined a march from Occupy Wall Street’s week-old encampment at Zuccotti Park towards the New York Stock Exchange, although police and metal barricades had prevented them from entering Wall Street. Demonstrators cavorted down the street chanting, “They got bailed out, we got sold out.” Now a crowd was forming around Stephens, with several people shouting along with him.

Marisa Holmes, an activist and film-maker who was involved with planning Occupy Wall Street, had come over to shoot Stephens’ emotional protest after hearing the commotion. As the police pounced on Stephens, Holmes refused to stop filming. She found herself being jostled by officers. The police decided to arrest her too. Before they could confiscate her video camera, Holmes hurled it into the crowd. A moment later, police had wrestled her to the ground, the camera still rolling.

In the footage, which Holmes later included in her 2016 film All Day All Week: An Occupy Wall Street Story, the camera violently jerks around for a few seconds and looks as if it might crash to the concrete. Then it steadies, turns back to the face of a young woman with pale skin and dark hair. “What’s your name?” someone yells. Trying to stay calm, the woman specifies her date of birth and says, “My name is Marisa Holmes”, before police drag her away.

The arrests of Stephens and Holmes were among the first of more than 80 made that Saturday. Although the media had paid little attention to Occupy — police, likely not wanting to draw attention, had been largely hands-off — it was now impossible to ignore. In one incident, a video of which was uploaded to the internet and soon went viral, two women were pepper-sprayed by a police officer. Footage showed that the women did nothing to provoke the attack, and it depicted them shrieking in agony on the ground afterwards. Jon Stewart rebroadcast it on The Daily Show a few days later.

Someone also uploaded Holmes’s arrest online, where it quickly amassed more than 300,000 views. But Holmes wouldn’t hear about this until later. For the next 24 hours she was kept in a crowded cell with a toilet that didn’t flush. (Her footage later helped her successfully sue the city for wrongful arrest.)

Holmes’s experience was incomparable to the brutal police repression she had witnessed in Cairo earlier that year, where she had spent a month following Egypt’s Arab Spring protests, which had led to the ousting of the country’s dictator Hosni Mubarak after 30 years in power. Holmes remembers thinking about political activists who, unlike her, spent decades in prison. “These are the stakes,” she told herself.

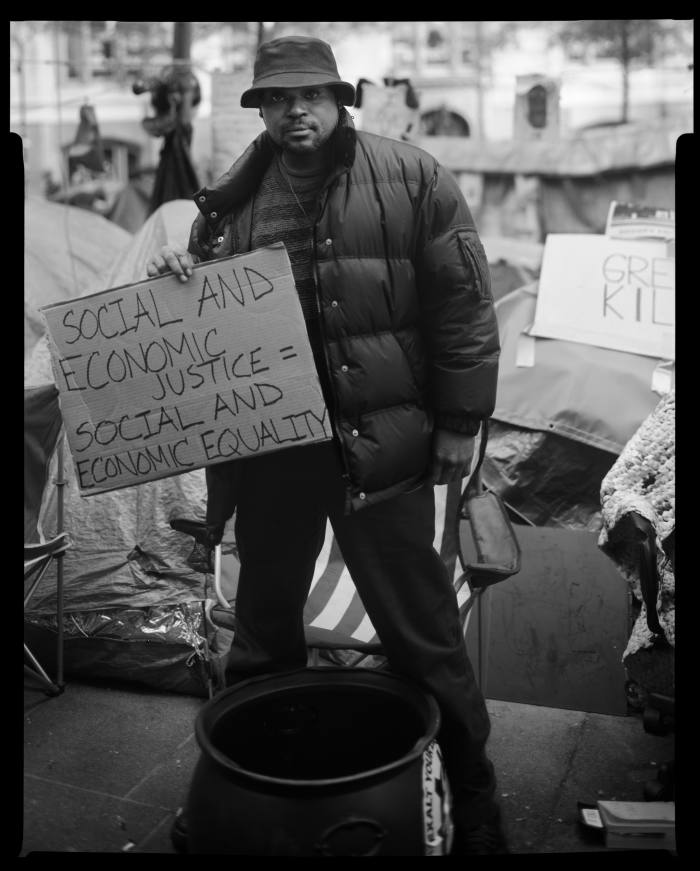

With America watching, Occupy continued to grow in the coming weeks — from the 40 people who turned up beginning on the first day of September 17 to 4,000 regular participants. It’s hard to get across the scale of what the occupiers thought they could achieve as that autumn in 2011 rolled on. Recent history has somewhat dwarfed the 2007-08 financial crisis. But prior to 2020, it had been considered the most severe global financial disaster since the Great Depression.

Triggered by predatory home lending and excessive risk-taking by financial institutions, it led to a wave of debt crises from Greece to Iceland, high-profile bank failures, corporate bankruptcies, mass lay-offs and the foreclosure of millions of homes. In June 2009, the US Federal Reserve reported that household net worth in America had fallen some $14tn over the span of two years. And yet, by the time Holmes and others were being arrested in lower Manhattan, very little had been done to bring the perpetrators to justice.

There was a feeling that Occupy was developing into an actual revolution, comparable to Egypt’s. “We really believed that at the time,” Holmes says, with a little laugh. “That we were engaged in an important historical moment with revolutionary potential. That we were part of this global wave that was already under way.”

It wasn’t just Wall Street. Occupy iterations popped up in cities all over the United States and around the world, from London to Australia, Rome to Nigeria. In the coming weeks, much was made of the fact that Occupy was leaderless and that, in microcosm at least, it seemed to be trialling a new brand of participatory democracy. And it was striking just how much the movement’s vertiginous rise took the establishment by surprise.

Today, though, conventional wisdom seems to be that Occupy Wall Street was a failure, a footnote revealing the origins of the phrase “We are the 99 per cent.” In the US especially, the energy seemed to swing violently to the other end of the spectrum at the end of the Obama years. But looking at the little-known origins of Occupy, you begin to see the great uncorking of a deep-seated anger that still resonates today. And with the hindsight of a decade, you begin to wonder if Occupy permanently changed the paradigm of protest.

I.

The idea for Occupy Wall Street was hatched in Vancouver, Canada, in an office belonging to an anti-consumerist magazine called Adbusters. Founded by Kalle Lasn, an Estonian émigré, in 1989, Adbusters specialises in self-styled “culture-jamming”, or subverting well-known ad campaigns and pushing radical leftwing ideals in the slickest of visual packages. Before Occupy, Lasn and the Adbusters team had long been trying to coin a catchy campaign to inspire a social movement against corporate capitalism.

“There’s a lot of secrecy about Occupy’s origins that was intentional because we wanted to promote this leaderless notion,” says Micah White, who worked at Adbusters at the time, although he lived in Berkeley, California.

Lasn had founded the magazine in the age of print but was keenly aware of the power of social media. “We figured that if the people suddenly learned how to use this most revolutionary tool in the palm of their hands, and were able to depose a guy like Mubarak, then surely we the people — especially the younger people in places like Canada and America — could also come up with huge demands and take the establishment for a big heave,” he tells me.

The Adbusters team came up with the concept for Occupy in the summer of 2011. In addition to the protests in Cairo, Lasn was inspired by the 15-M movement against austerity in Spain, which had led protests and occupations earlier that year. (15-M was named after the date, May 15 2011, that the Spanish anti-austerity protests began.)

While writing Adbusters’ inaugural call for Occupy, Lasn came across a “profound and beautiful” quote by 15-M activist Raimundo Viejo. Viejo’s quote said that while the anti-globalisation approach had been to “attack the system like a pack of wolves”, with an alpha-male leading the pack, 15-M was different: “Now the model has evolved. Today we are one big swarm of people.” Lasn says that it was Viejo’s quote that made his call for Occupy catch fire with activists.

I met Viejo at a café in Barcelona in early August. He recognised this as the kind of thing he was saying and writing at the time, but couldn’t remember when or where he had given the quote. Yet those words would spark a global wave of activism. And in some ways, 15-M was the true start of the Occupy movement.

In total, around eight million people in Spain joined the protests. It felt to many, not only activists such as Viejo, that Spain was on the brink of a revolution. Later Viejo would become an MP for the Spanish leftwing anti-austerity party called Podemos that emerged out of 15-M. His friend and fellow activist Íñigo Errejón would become one of Podemos’ most influential politicians, while another member of their group, Pablo Iglesias, would become its leader.

A staunch leftwinger who came from a family of political activists, Viejo, aged 42 at the time, had been involved in many protests. He didn’t expect 15-M to be particularly remarkable. As he entered Puerta del Sol, Madrid’s expansive central square, on the second day of the protests, Viejo realised how wrong he had been. “I was just, like, ‘Wow! What is happening?’” The square was packed; thousands had shown up. He remembers saying to Errejón, who entered the square alongside him: “This is going to be something really special.”

The protests kept growing. On May 17, there were some 4,000 people. Influenced by the Arab Spring protesters in Tahrir Square, they decided to occupy Puerta del Sol, establishing encampments and holding general assemblies to make collective decisions. There were no obvious leaders. Social media, particularly Facebook, was essential to organising and keeping momentum, as it had been in Egypt. The demonstrators were also referred to as indignados, meaning “the outraged”. Throughout the summer, opinion polls showed that up to 80 per cent of the Spanish public supported the indignados’ demands.

Across the Atlantic in California, Micah White was watching footage of the protests. Like his Adbusters boss, White wondered if America could be next. He had been reading Adbusters since he was a teenager and working for Lasn since 2005. “It was my dream job,” White recalls, “and I had basically wormed my way up from being an intern to being his closest collaborator.” He describes Lasn as “kind of an eccentric visionary, who is also very reclusive and doesn’t meet with many people”. Neither of the men could stop watching what was happening in Tahrir Square and then in Spain. “All of a sudden,” says White, “it felt like revolution was possible in the world.”

They had been waiting for just such a moment. Lasn and his team in Vancouver would meet for brainstorming sessions every Monday or, more often, “when things got really hot” politically. They sat around a big round table for intense strategy sessions focused on how Adbusters could make the wave of protests crash into North America: “Before Occupy started, we were constantly trying to sort of figure out what is the true geopolitical state that the world is in,” Lasn recalls. “We were constantly looking for opportunities to intervene in revolutionary ways.”

Lasn, then aged 69, was an Estonian whose family had fled their home country after it was invaded by the Soviet Union. After a stint in a refugee camp the family moved to Australia. Lasn worked in marketing and advertising in Japan before moving to Canada in 1970. “I’ve had a revolutionary mindset ever since I was a refugee growing up in the refugee camps after the second world war,” he says, though it was the 1968 Paris protests that really politicised him. He had longed for a similar revolutionary moment ever since and had tried to trigger it himself with various campaigns. One that he was involved with, Buy Nothing Day, was a moderate success, eventually reaching 65 countries. But in 2011, the climate seemed ripe for another tilt.

The concept that Lasn and the Adbusters team came up with fused the Tahrir Square model — congregating in a place of symbolic importance to make a singular demand — with the consensus-based assemblies of Spain’s indignados, where the demands would bubble up from the people. The key was to come up with an incendiary meme — an image, say, or a slogan — that would attract people to the idea.

White says that he and Lasn decided that “Occupy Wall Street” should be that meme. Using the Adbusters Twitter account, White coined the hashtag #OCCUPYWALLSTREET on July 4 2011. He posted the meme on Reddit, political forums and activist websites associated with the movement called Anonymous. He also registered @OccupyWallStNYC, the first Occupy handle on Twitter.

A centre spread in that month’s issue of Adbusters featured a poster of Wall Street’s Charging Bull sculpture with a ballerina balanced atop it and protesters emerging from a fog of tear gas below. A red-coloured headline read: “What is our one demand?” At the bottom were the Occupy Wall Street hashtag and the imperative “BRING TENT”. The date given, September 17, was chosen at the behest of Lasn; it happened to be his mother’s birthday.

The poster was followed by the first of many “tactical briefings” for interested activists, announcing a “new form of protest” and stressing the need for a crowdsourced single demand; it was fronted by Viejo’s 15-M quote. (The briefing suggested the demand could be to rid politics of corporate donations.) Apart from being printed in about 40,000 copies of Adbusters, the call for Occupy was sent out to some 90,000 email subscribers.

A 26-year-old anarchist and computer programmer called Justine Tunney read about Occupy on her RSS feed and the next day registered the domain OccupyWallSt.org. It would become the movement’s de facto website. In the following weeks, Adbusters started receiving 10 times as many emails as usual. Lasn was bowled over: “All of a sudden it felt like we had touched some kind of a nerve.” White agrees: “The stars were so aligned. It was unbelievable.”

II.

In New York, the Adbusters meme quickly circulated among activists, many asking what Occupy Wall Street was. “Initially, the reaction was very dismissive,” Holmes, the activist and film-maker, recalls. Who were these guys in Vancouver trying to get people thousands of miles away in New York to fight their campaign for them? But some were receptive. On August 2, Holmes, David Graeber — an influential anarchist anthropologist and activist from New York, then on sabbatical from Goldsmiths, University of London — and others convened at the Bowling Green park, home of the famous Charging Bull statue, where they discussed Occupy.

That night, Graeber sent an email to White asking how the Occupy Wall Street campaign had started. White explained as best he could, and emphasised that Adbusters would not try to exert any control. “We made a special effort to reach out to anybody there in New York,” Lasn says. “We were the spark who sort of set up the concept, the idea, the strategy. But [Graeber] was the guy who actually made it happen.” Lasn wanted to avoid “playing that top-down game”, echoing the 1968 Paris protests. “If you want to launch a world revolution, then don’t try to control the damn thing.”

Involved with activism since graduating in 2008 amid the financial crisis, Holmes had just come back from filming protests in Cairo. But in Egypt she had increasingly felt she should be trying to make a difference at home, and her friends there agreed. “You need to go back and organise in your own context and make the revolution there,” they kept telling her. Soon after her return, Holmes came across the Adbusters call for a Cairo-style occupation and says she thought, “Oh yeah, I’m ready for a Tahrir moment.”

New York was ready too. Bloombergville, a demonstration against the then-mayor’s public sector budget cuts, had already led to dozens of people camping outside City Hall, a few blocks north of Wall Street. Student occupations in the UK against the government raising the cap on tuition fees and cutting higher education spending were also inspiring similar actions in the US. There had been simmering anger and frustration in the wake of the economic crisis. President Obama had been elected on a popular platform but had done little to take on the banks, while the Federal Reserve kept printing money. Meanwhile, millions were still losing their homes, and there was record unemployment.

Over the following six weeks, the New York City General Assembly (NYCGA) formed by Graeber, Holmes and others met with several different groups to plan Occupy. They invited activists from previous social protest movements — anti-nuclear, antiwar — that had experimented with participatory democracy and direct action. Anonymous, the online activist group, also joined planning sessions as it sought a move offline. In one outreach meeting before Occupy, Graeber and others crafted the slogan: “We are the 99%”. (Although Graeber is often credited with coming up with it, he maintained that the slogan was created collectively to the day he died in 2020.)

In the week before Occupy Wall Street began, White handed control of the @OccupyWallStNYC Twitter account to Holmes, who became a crucial member of the so-called facilitation team. From having 6,000 followers, the account would grow to tens of thousands in just a few weeks.

III.

On September 17, a few dozen protesters met at New York City’s Bowling Green park and circled the Charging Bull depicted in the Adbusters poster. The bull sculpture had been barricaded, and lines of police were blocking access to Wall Street. Following maps that were handed out, the demonstrators then marched to Zuccotti Park.

Once there, a myriad of meetings started: “People were talking about, you know, the economic crisis and how they were affected and what a transition away from capitalism might look like,” Holmes says. In one address to the crowd, a young woman from Madrid urged demonstrators to persevere, assuring them that the longer they stayed in the square, the more people would come.

By the evening, more than a thousand people had shown up, stunning Holmes and others on the facilitation team. They decided to hold a general assembly, which Holmes facilitated alongside Lisa Fithian and Graeber. Using a megaphone that kept squeaking and feeding back, Holmes told the crowd that they needed to decide together what to do next. They had gathered everyone into an enormous circle around the central speaker, but Graeber and others noted that this meant the speaker with the megaphone always had their back to one part of the crowd. And that’s how they came up with one of Occupy’s innovations: the “people’s microphone”.

Instead of using a megaphone, the speaker and people at the centre of the crowd called “Mic check!” to get people’s attention, and then got the crowd to repeat each line, so that everyone could hear. Holmes and the others believed that the participatory nature of this helped engender the community feeling that made people want to stay in the square. After three or four hours of debating, the crowd made a democratic decision to stay overnight. A few hundred slept in Zuccotti Park that first night.

The next morning, the occupiers marched on Wall Street for the ringing of the opening bell to the stock exchange. At first, the bankers didn’t take them seriously. But they kept coming every day. In Zuccotti Park, the occupiers organised free food, which morphed into the “people’s kitchen”. Only a few dozen people camped out each night to hold the space, with larger crowds returning each morning.

They didn’t think the occupation would last long. “We thought maybe a couple of days max, and then the police will come in and clear us out, because that’s what had happened in the financial district in previous mobilisations,” Holmes recalls. The police made sporadic arrests, ordering the odd tent and structure to be taken down, but mostly they and the owners of the square, Brookfield Office Properties, seemed to have banked on it fizzling out without anyone noticing. “But then, of course, everyone did,” Holmes says.

The internet helped. While the media largely turned a blind eye for the first week, the occupiers were live-streaming everything, spreading the word on social media and getting plenty of views. A week after the arrests on September 24, the occupiers captured the news cycle again with a march over the Brooklyn Bridge. As police surrounded the protesters in the middle of the bridge, the occupiers chanted: “The whole world is watching!” Mass arrests followed. Holmes points to social media’s power to bypass the traditional gatekeepers of information at big media organisations as one of the factors allowing news of the protests to spread.

Occupy was growing far beyond the nucleus of its more anarchist-minded organisers. Unions and traditional leftwing activists were joining, and the “We are the 99%” slogan was catching on. Some Democrats even began to swoop in, wanting to usher the occupiers into the progressive wing of the party. The then New York public advocate Bill de Blasio showed up at Zuccotti Park and conducted an interview praising Occupy.

But most of the core occupiers did not believe in traditional electoral politics. The whole point of Occupy Wall Street was to build something different. And after achieving the feat of holding the square for a month, they needed to figure out what to do next. While Lasn and White at Adbusters had suggested from a distance some ideas for key demands that people could focus on, their efforts were politely rebuffed.

Instead of making appeals to the government, the occupiers wanted direct action. “We didn’t have demands, but we had a vision,” Holmes explains. It was a vision of direct democracy, mass participation and horizontal decision-making — undeniably anarchistic, but capable of attracting ordinary people. It wasn’t perfect. Even White claims that the facilitation committee had “overwhelming power” over the assemblies, and Graeber has sometimes been depicted as Occupy Wall Street’s de facto leader. But Holmes disagrees with this characterisation. “I think the most important thing that David did was bridge previous movements,” she argues. “He was really most effective at operating kind of in the background, making these connections and doing education.” Graeber was, after all, a professor.

Echoing the protesters in Tahrir Square, the occupiers renamed Zuccotti Park as Liberty Plaza. Just as with Tahrir Square, this had actually been its original name. (John Zuccotti was Brookfield’s chair and the square had only taken on his name in 2006.) And to the occupiers, it was starting to feel as if something as big as the Arab Spring might be possible. “We saw ourselves as part of a global revolution that was already under way. And our goal was to practise the new society that we wanted in the present,” Holmes says. The fact was that Occupy groups were appearing in cities all over the world.

IV.

In Spain, the indignados had not given up after their summer of mass demonstrations. They called a global day of action for October 15, and thousands of activists in multiple countries took up the call. Occupy Wall Street marched en masse to Times Square. In Rome, a huge demonstration turned into violent clashes with police. Protesters in Hong Kong camped out beneath the HSBC headquarters. The date was also chosen for one of the biggest and most enduring iterations of the movement: Occupy London.

As with Occupy Wall Street, there was something in the air in the months preceding the London occupation. Apart from actions by the protest group UK Uncut and the wider anti-austerity movement, online activists involved with WikiLeaks and Anonymous were increasingly moving offline. “Those three groups had totally separate plans going into October, but all settled on that sort of 15th October date as the date something would happen,” recalls Naomi Colvin, who became one of Occupy London’s unofficial spokespeople and was involved in planning meetings beforehand.

Colvin says that very early on in the planning for Occupy London, people from Spain’s 15-M movement came to offer advice and provided a training session on the eve of launching. “We were given the proper handover of knowledge about what you do when your occupation comes under attack, and how you organise it, and having people off site and on site and how to make sure that your comms channels don’t go down,” she says. “Which was very cool.”

The target of the demonstrators on October 15 was the London Stock Exchange. But the would-be occupiers were diverted by police and found themselves next door, in the open space outside St Paul’s Cathedral. They decided to stay there — more than a thousand of them. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange gave an impromptu speech on the steps of St Paul’s in support of the occupation. He revealed that WikiLeaks was planning to target financial institutions along with corporate tax evasion, a key target of UK Uncut.

Colvin says that it was obvious very quickly that Occupy London was going to be big. “I’ve never really known a sense of momentum like it,” she says. This was partly because Occupy Wall Street had already become a huge story, so there was an expectation something would happen in London. From day two, Colvin’s phone was ringing from early in the morning until late at night, as the media frantically covered the story.

What impressed one of Occupy London’s key figures, Jamie Kelsey-Fry, was the way it attracted ordinary people. “This was not the usual suspects,” he tells me. “People from all kinds of backgrounds were being drawn to the camps.” During the assemblies, which were soon attracting more than 2,000 people to the steps of St Paul’s, people who had never taken part in politics and were often terrified to speak found their voice. “It was people that were speaking a very visceral politics,” Kelsey-Fry says. “It came from the gut.” There were street cleaners, young single mums, struggling grandmothers and also some students and professionals. “But this was different, yeah?” Kelsey-Fry says — the latter were the exception rather than the rule. “This was not intellectual. This was not: You have to have a bloody degree in politics.”

Kelsey-Fry also claims that bankers would turn up at the camp late at night, fresh from champagne bars. “You have to win,” he claims they told him. They apparently felt trapped in a cycle where they were “duty bound to completely fuck the world”, and felt awful, because their lives were meaningless in spite of their wealth, Kesley-Fry says. “You end up sitting there, with some middle-aged guy that’s crying his eyes out on your lap.”

“Death by consensus” was a real problem for Occupy London, Kelsey-Fry admits, as it was for other iterations. “You’ve got no idea how horrible some of those assemblies were, where we decided something like ‘We have to make sure that there’s no alcohol in the tea tent’, and it went on for about three hours, sitting on freezing flagstones, hearing everyone out,” he says, laughing.

Colvin recalls something similar after the City of London Corporation sent notices to the occupiers as a prelude to taking them to court, and it was decided to put the legal decision-making to the general assembly. What followed were three painful evenings of hashing out the decision and then the wording of the legal response collectively. But the resulting document was much stronger than if lawyers or any of the occupiers had written it individually, Colvin says.

Occupy London was not a conventional project of the UK left, but much broader. A couple of months into the occupation, the office of the then Labour leader Ed Miliband made what Colvin calls a “half-hearted” overture. When organisers brought this to the general assembly, the crowd was not “fussed”, Colvin recalls with a chuckle. “Nobody cared. They just weren’t interested in engaging with it at all.”

V.

A month in, the occupation in Zuccotti Park — or Liberty Plaza — was becoming more permanent. Problems were emerging too. Homeless people were arriving in the camp, and some activists later admitted they were not equipped for that. Deliberate disruptors were a perennial issue. How do you exclude a troublemaker from a consensus-based assembly? There were thousands of regular participants and more than 100 working groups, so it was also getting harder to keep track of the decisions being made. The New York City General Assembly had received $1m in donations, while other groups had received very little, leading to tensions. At a meeting captured in Holmes’s filming, one activist laments that “money is tearing the movement apart”.

By early November 2011, Occupy Wall Street’s activities were slowing down. Most of the occupiers who had been there from the start were exhausted. General assemblies were now so large that the vaunted people’s microphone had grown unwieldy, with each line of a speaker’s address taking several seconds to ripple out to the edges of the crowd. There were attempts to create a more functional decision-making process called the Spokes Council, but it faltered.

And then, after two months of holding squares across the United States, Occupy was hit by the authorities. In a co-ordinated action between Wall Street, Homeland Security, the FBI and local police, hundreds of occupations were cleared around the country. On November 15, police began clearing Zuccotti Park. Anyone who refused to leave was arrested. Mayor Bloomberg said he had grown “increasingly concerned” that the “occupation was coming to pose a health and safety hazard to protesters and the surrounding community”.

Earlier that day, Adbusters had emailed out its latest tactical briefing, which called for Occupy to hold a party in mid-December, declare victory for having spread globally and then leave the encampments. Emailing Lasn, White wrote that the timing of the briefing so close to the eviction was “eerie”. But when White called Lasn the following morning to report what he’d heard of the “military-style operation” by police the night before, Lasn, who was in the bath, got worked up. “Oh my God, Bloomberg — he’s made a fucking mistake here!” he remembers thinking. The clampdown, he believed, would set the scene for a possible new phase of action, instead of Occupy fading out as New York’s freezing winter set in.

This time Lasn’s instincts were off. Occupiers returned to Zuccotti Park the day after the eviction, but tents were no longer permitted. A couple of days later they tried to shut down the New York Stock Exchange, but were thwarted. There was a sit-in protest at the Brooklyn Bridge and repeated scuffles with police at Zuccotti Park as occupiers attempted to retake the square. All failed. The movement never really recovered.

“It was obvious we had lost,” Micah White later recounted in his 2016 book The End of Protest. “The bankers weren’t going to be arrested and the influence of money on democracy wasn’t going to be halted. The decisive moment had passed.”

A week after Zuccotti Park was cleared, President Obama was giving a speech at a school in New Hampshire when yells of “Mic check!” in the audience interrupted him. Occupiers had infiltrated the event and used the people’s microphone technique to plead with the president to end the repression of Occupy. After the protesters were removed from the crowd, Obama acknowledged the “profound sense of frustration” among struggling Americans. Then he returned to reading from the autocue.

The tactics — portraying occupations as a health and safety issue and clearing peaceful demonstrators by force — would be deployed in countless other cities and replicated worldwide. In the US, a total of more than 7,000 occupiers were arrested, with many subject to police violence. “Occupy either had to leave and come back, or it would just be destroyed. And so it chose to be just destroyed,” White reflects.

Within a week, many of the occupations around the world were gone. Notably, Occupy London persevered through the winter. As in Zuccotti Park, the authorities claimed the space outside St Paul’s Cathedral needed to be cleared for hygiene reasons, but several clerics and the cathedral’s chancellor resigned after it was revealed that the authorities had been plotting to force the occupiers out.

In February 2012, the City of London Corporation finally won a court ruling against Occupy London. And so it was that the world’s last major occupation was eradicated. Some occupiers retreated to a second location at Finsbury Square and promised this was “just the beginning”. But as with Occupy Wall Street, the moment had passed.

VI.

Micah White left Adbusters in 2013 and declared Occupy a “constructive failure”. In his book, he argues that mass protests are no longer an effective tool for bringing about change. Speaking to me via video call, White now believes that Occupy should have made a plan to leave and come back, rather than trying to endure both New York’s winter and its police. “The occupiers were delusional,” he says. “They were just like living in a fantasy land. The encampment model doesn’t actually manifest sovereignty over the government, even if it does manifest a better form of democracy temporarily. It was a good experiment, but it was a dead end.”

Yet Occupy left behind a powerful if not always visible legacy. Many occupiers splintered off into myriad campaign groups, particularly around climate activism, and many believe their movement pushed the socialist independent senator Bernie Sanders to announce his run for president in 2015. By the time of the primary campaigns for the 2016 presidential elections, inequality was one of the major talking points across the spectrum. Even conservative GOP candidate Ted Cruz said that “the top 1 per cent earn a higher share of our income nationally than any year since 1928”, while Marco Rubio, another Republican, proposed subsidies for low earners. Biden’s Democrats are now trying to pass a bill reforming campaign financing — the “one demand” Adbusters wanted Occupy to adopt.

One key occupier from London, Tina Rothery, is standing to be leader of the Green party. Other occupiers from London went on to fight deportation flights as part of the activist group Stansted 15. Even the UK’s then prime minister David Cameron started talking about “crony capitalism”. The “We are the 99%” slogan was embraced by the Bernie Sanders movement, as well as quite a few Trump-adoring QAnoners.

Occupy failed because it did not have a clear demand or structure, or so goes the most common argument. But perhaps this is judging by another era’s standards, one in which, say, striking workers demanded — and sometimes won — better conditions. Activists such as Graeber and Holmes say they wanted to demonstrate that, even if it wasn’t perfect or fully formed or, indeed, capable of enduring, Occupy’s leaderless organising could in itself embody the change they believe the world needs. As Holmes’s voiceover says early on in her documentary: “Together we wanted to build a new world. And for a moment we did.”

The decade of fury that followed has been marked by mass demonstrations of every conceivable kind. There have been global climate strikes, Black Lives Matter protests and marches in defence of women’s rights. Pro-democracy protests in countries around the world repeatedly caught ruling elites off-guard. There have also been far-right rallies, fuelled by resentment and paranoia. There were stunning protests in Hong Kong defying the world’s most powerful repressive state. And, in January, there was the deadly storming of the seat of the world’s most powerful democracy. As with Occupy, all of these have been reactions to massive challenges requiring co-ordinated action to allay — problems that can leave people feeling powerless and angry or as if justice is forever being delayed.

With the world now starting to emerge from lockdowns and Covid-related restrictions, the pause in the repeated mass actions of the past decade is coming to an end. Lasn, a person with direct responsibility for launching Occupy, is keenly aware of the moment. “I don’t at all agree with this idea that somehow Occupy Wall Street failed. It didn’t,” says the 79-year-old who still helms Adbusters. “I sort of vacillate between feeling like humanity’s fucked for ever and, at the same time, that ‘My god, there’s never been an opportunity like this.’”

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first