Top players seek a financial game plan for life after sports

In his 11-year career in North America’s National Football League, Adewale Ogunleye, made hundreds of tackles. But the defensive end, who’s almost two metres tall, also learned to block approaches from the wannabes claiming to be the “next Warren Buffett”.

“It felt like everyone’s idea just needed my capital,” Ogunleye tells the Financial Times. “You feel this sense of guilt of having to say ‘no’, and it’s hard because you grew up with a lot of these people, they’re from your neighbourhood or they’re even in your family.”

Athletes such as Ogunleye, who played for the Miami Dolphins, Chicago Bears and Houston Texans in the NFL, can earn tens of millions of dollars in salary and endorsements over their careers. Even back in 2004, Ogunleye’s contract with the Bears was worth $34m over six years.

Rising broadcast revenues and sponsorship deals have powered the world’s elite sports leagues and teams to greater financial heights. That has translated into huge salaries for athletes, who must balance intense training schedules with the need to protect and build on the capital they accumulate. Athletes are also generating more income from social media and other outside interests, increasing the complexity of their finances.

The coronavirus pandemic was a reminder of the finely balanced nature of elite athletes’ incomes, as their employers’ revenues plummeted. Some were caught out of contract or released at an inopportune moment. The high salary system has also drawn attention to the pressure on clubs that sign the biggest contracts: FC Barcelona allowed Lionel Messi, the greatest footballer in its history, to leave because of the burden of his salary.

The problems faced by the top players in football or other well-funded sports might seem negligible, particularly after an Olympic Games in which athletes described training with paltry funding or commercial support. But overcoming the difficulties of managing a short, high-risk earnings window offers lessons to many with volatile income sources, inside and outside sport. How should a pot of earnings be invested: in property, shares or other assets? How should players plan for retirement with little idea of their post-playing earnings?

Star footballers can become millionaires virtually overnight, even as teenagers. With limited experience and understanding of finance, money is easily frittered away; and not all the agents, friends and financial advisers they encounter have their best interests at heart.

Elite sportspeople, current and former, tell the FT that unscrupulous characters present them with all manner of get-rich-quick schemes. But there are also signs of an increasing maturity among players when it comes to managing their financial future.

The value of good advice

In 2018, just over half (52 per cent) of professional athletes surveyed by the Professional Players Federation, a UK group spanning numerous sports, including rugby, cricket and football, encountered financial difficulties within five years of ending their playing careers.

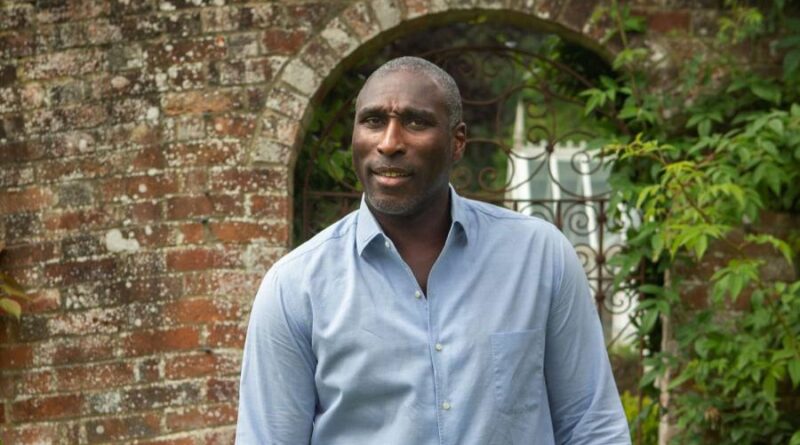

Bad investments, theft or divorce are three common ways in which a player’s finances can go off the rails, says Sol Campbell, a centre-back who twice won the English Premier League with Arsenal. High-stakes gambling is another vice that has cost footballers millions.

“My observation is, no one’s safe,” says Campbell, one of a handful of Englishmen to score in the Uefa Champions League final. “Even if you’ve got £50m in your bank, no one’s safe. That could go, like that.”

Trust is crucial to off-field affairs. Athletes heavily rely on their agents, the intermediaries who handle everything from transfers to contract negotiations with teams and connecting stars to wealth advisers.

The combination of youth and sudden wealth makes athletes a target for fraudsters and scam artists. Athletes alleged more than $600m in fraud-related losses between 2004 and 2018, according to EY. The professional services firm, which analysed data including bankruptcy filings, warned that athletes are “becoming a bigger target of fraud”.

Ollie Phillips, the former rugby union player and England Sevens captain, says he discovered he was the victim of mortgage fraud.

“Thirty properties in my name, [they] borrowed £6.5m in my name, forged my signature, whole shebang. It ended up being a 12-year court case,” he says.

Phillips, who now works in the property sector at PwC, the professional services firm, says players deserve more safeguarding.

“You meet lots of successful people who are genuinely successful,” he says. “Then you meet lots of other people . . . they throw lots of cash around and make life seem amazing. Underneath, it’s all built on a pack of cards.”

On the ball with finance

Today’s athletes may be no less vulnerable to poor decisions or skulduggery, but players and advisers say they have become increasingly commercially aware and savvy.

The financial crisis of 2008-09 was a turning point, according to Marlon Fleischman, an agent and co-founder of Unique Sports Management, who has witnessed a “real shift in mentality” among players since then.

Traditional agents are transforming into business managers, who are capable of building specialist teams of accountants, tax advisers and wealth managers for players, according to Fleischman, whose clients at USM include Premier League footballers such as Everton’s Andros Townsend and Manchester United’s Aaron Wan-Bissaka.

“We’re entrusted with a player’s career,” he says. “And that means by the time they finish their playing career they should not be at a point where they’re having to . . . sell off all their houses or assets . . . They should have real long-term wealth.”

Jason Katz, managing director and private wealth adviser at UBS, says: “What I’ve witnessed more in the last year than I ever have in my whole career is that athletes are building these teams of financial professionals around them,” he says. “They’re looking for ways to manage their finances to create generational wealth.”

In some cases, athletes are learning the language of law and finance to set themselves up for careers after sport.

“I didn’t know anything about money,” says Ogunleye, who addressed that by completing an MBA at the George Washington University School of Business after leaving the NFL. In 2019, he joined Katz at UBS, where he is head of the bank’s athletes and entertainers strategic client segment.

Gareth Farrelly, a former Premier League footballer who played for Aston Villa, Bolton Wanderers and Everton, was hospitalised in 2008 after almost dying from a splenic aneurysm. With hopes of returning to the Premier League fast fading, his recovery was interrupted by a call from tax authorities about an unexpected bill from a film investment scheme made on his behalf.

“These people operated with absolute trust,” he says. “They were part of our social circles, they were in players’ lounges, they knew all of our families, but fundamentally they were selling us products that for me were not in the best interests of professional athletes.”

Farrelly decided to go to university to study law after a “negative” meeting with a lawyer who used jargon and spoke in a language he didn’t understand. “It was like the Enigma code,” he says. Now a sports and litigation lawyer, he works with the English Football Association, the governing body, and is an arbitrator at the Court of Arbitration for Sport, the Switzerland-based arbiter of global sports disputes.

But most athletes will not end up practising law or becoming a finance professional. Uefa, European football’s governing body, has turned to former pros to equip the next generation with the knowledge they need to manage their finances, whichever post-playing career they choose.

Gaizka Mendieta, who played for Spain at the 2002 Fifa World Cup and was twice a runner-up in the Champions League with Valencia, backed the launch of a financial management course set up by Uefa and Spanish bank Santander in 2019.

He counts himself lucky because his father, a former goalkeeper, guided him on the pitch and his mother advised him to buy a diverse pool of assets. His investments range from property to stocks and shares and even a restaurant business in London.

“I, we, made mistakes in terms of investing,” says Mendieta. “Still . . . when I finished my career I had something to rely on, I didn’t have to be concerned about my finances.”

Wealth that lasts

Ben Smith, a financial planner at FLM, which advises roughly 50 athletes and is an affiliate of FTSE 100 wealth manager St James’s Place, said it is important to get athletes into the habit of saving from an early age.

“Too many people don’t have that advice and then they get into bad habits and then it’s very, very difficult to ‘downscale’ your lifestyle, as it were,” he said. “With every decision you make with your money, you should make sure you can sleep at night.”

Katz says advising athletes typically starts with education and making finance relatable. There is no “one size fits all” approach for athletes, as their income can be inconsistent and derives from multiple sources, ranging from playing contracts to endorsements and appearance fees.

The complexities, particularly for athletes who move across the US or Europe to play for different teams over the course of their careers, are abundant. For younger, less-established athletes looking to purchase a home, Katz often advises them against buying their main residence right away. “They may get traded or sign with a different team,” he warns.

Given the low interest rate environment, advisers say it can make sense for up-and-coming athletes to take out a mortgage on up to 70-80 per cent of the value of their home, while wealthier athletes have an opportunity to consider borrowing the entire amount with a pledge.

With the risk of injury, less job security and the brevity of an athlete’s career, Katz warns that they should hold a higher proportion of cash, or another form of liquidity, as part of a portfolio of assets.

Sometimes the problem is much simpler. Katz describes meeting an athlete with “millions upon millions of dollars” sitting in a bank account that yielded no interest.

“I said to him, ‘If . . . I told you at the adjacent table there was $150,000-200,000 in cash, I know where you came from and how you had to fight tooth and nail, you and I would dive on that money . . . You’re effectively leaving that much money on the table.’”

Pensions are now common in elite sport. Campbell, the youngest of 12 siblings, says starting his pension at 17 or 18 years old was one of his “best decisions”. It’s a sentiment shared by Phillips, who took out a self-invested personal pension at 19 on the advice of private wealth friends at UBS. His timing meant he was eligible to take benefits from the age of just 35, although changes to UK pension rules mean that is no longer an option for today’s athletes.

Though players still turn to friends and family to act as their agents, particularly at the early stages of their careers, Campbell says professional advisers and expert guidance become essential as top athletes progress.

Like many of his generation, the ex-footballer typically prefers to invest in property instead of shares. “Most footballers want . . . their main capital safe,” Campbell says. Those who bought homes 10-15 years ago can refinance to invest in other assets, from property to higher-risk cryptocurrencies, he adds.

However, he believes the stakes are often higher for players of colour, who are rarely selected to manage football teams in England or the rest of Europe once they finish their playing careers — a common post-playing route for athletes.

“You’ve got to be spot on [with investment decisions],” says Campbell. “A lot of players of colour had to refinance their houses or sell their houses . . . to pay debt and move on again.” Many will start their own businesses to gain some control over the future, he adds.

Thirst for knowledge

Players are increasingly hungry for information about crypto assets, start-ups, stocks, shares and foreign-exchange trading, advisers say. “They ask all these questions because they don’t want to look silly in front of their peers in the changing room,” says Fleischman.

Professional athletes are less willing simply to show up for a promotional video shoot and take a pay cheque for a traditional product endorsement, he adds, with increasing numbers considering work with start-ups in exchange for equity instead of cash.

Thomas Hal Robson-Kanu, the Wales international footballer, has balanced his own Premier League career with starting his own business, the Turmeric Co, which uses the root of the bright orange plant as an ingredient in health drinks.

The business, which was founded in 2018, has about 35 employees and is moving to a 15,000 sq ft manufacturing facility north of London to meet demand. It declined to give details of revenues, but consumer demand for turmeric soared last year amid a rush for so-called “health halo” ingredients with immunity benefits.

At 32, Robson-Kanu — who just parted ways with West Bromwich Albion, a club relegated from the Premier League last season — is in the latter stages of his playing career but planning for his future.

The part-Nigerian player says he has been fortunate to build up an array of trusted advisers over the years. Babatunde Soyoye, the Nigerian national who co-founded Helios Investment Partners, the private equity firm backing the National Basketball Association as the North American league expands into Africa, is a “great sounding board”, says Robson-Kanu.

Property was one of the footballer’s early investments, though he later turned his attention to technology stocks and cryptocurrencies. He bought his first bitcoins around 2015 when the price traded mostly in the $200-$300 range, but he is keen to warn that crypto assets are speculative and prone to crashes. Amid pressure on club revenues, crypto sponsorship is on the rise in sport.

“You’ll have football players who look after their own financials and make their own decisions, and then you have football players who will literally have an allowance given to them by their advisers,” says Robson-Kanu. “Neither is right or wrong.”

For the most garlanded footballers, their staggering levels of earnings may insulate them from the worst effects of poor decision-making. But for mid-level players and those in other, lower-income sports, managing their money over a lifetime is a tougher business. Just like on the pitch, mistakes are punished in ruthless fashion.

“We need to try to make football safe for players,” says Mendieta. “If you think that money will last for ever, believe me . . . it does not last for ever.”