Paying for the pandemic: US politicians gamble on sports betting

Legislators in New York state barely slept before Easter. In the nights running up to the weekend holiday, the lights were still on in the state government’s Albany offices at 3am, as politicians battled over whether to open the door to online sports betting — a proposition unthinkable last year, but now an essential part of the state’s $212bn annual budget.

Spurred by pandemic-linked revenue shortfalls, lawmakers were pushed to legalise the pastime — which some estimates suggest could raise $300m annually in state taxes — and decide how tightly to regulate the budding industry. New York’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, had repeatedly opposed the move stating that it would require a change to the state’s constitution. “This is not the time to come up with creative, although irresponsible, revenue sources,” he said in January 2020.

But facing a $15bn budget black hole and several personal scandals, Cuomo is now backing online sports betting. On Wednesday, New York became the 16th US state in three years — and the largest to date — to allow online gambling after the legislature voted to approve a budget pushed through so quickly that nearly a week later, “the industry is still trying to make sense of it”, a lobbyist close to the process says.

Only a handful of operators will be allowed to offer online bets and the tax rate on each wager could be as high as 50 per cent, yet the competition for licences in potentially the most lucrative state for online betting in the US is likely to be fierce, say operators, bankers and sports executives.

The drama in Albany illustrates just how swiftly conventional American attitudes on sports betting have changed. The rush follows a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that struck down a federal ban on sports betting and online gaming outside of Nevada that had stood for 26 years. The first state to legalise the activity was New Jersey but since the pandemic, there has been a domino effect as state tax departments scramble to replenish much-depleted coffers.

“The revenues are the most important thing right now that governors are seeing . . . There is really nothing else you can legalise where you can get $300m per year [in tax revenue],” says Chad Beynon, a gaming industry analyst at Macquarie Group, estimating the New York take.

Operators who were enthusiastic about the US market before are now ecstatic. Estimates in 2018 of a total market size of around $8bn in sports betting turnover by 2024 look wildly conservative. In March, Flutter, owner of the online gambling companies FanDuel and FOX Bet, said it expected the market for its brands to exceed $20bn in revenues by 2025 — double the forecast it made this time last year.

The law change has also kickstarted a wave of takeovers as companies from outside the US seek a foothold and those inside the country seek technological help.

“The market is going bananas both in terms of revenue and market expansion,” says James Kilsby, US vice-president at Vixio Gambling Compliance. “There is a decent chance we could see New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Michigan become the third, fourth and fifth largest regulated online gambling markets in the world by the end of this year, only behind the UK and Italy.”

In the first two months of 2021, revenues from sports betting in the US were $576m on total bets of $7.8bn, according to the American Gaming Association, up from $262m and $4.1bn, respectively, in the entire first quarter of 2020.

Those figures don’t include the biggest individual betting event in the US sports calendar: the annual men’s college basketball championship known as March Madness, a two-week tournament which concluded with Baylor University’s upset win over Gonzaga on Monday last week. In 2019 the AGA estimated that $8.5bn would be gambled on March Madness, more than half in informal pools between family and friends.

The speed and gusto with which operators have plunged into the US has invited comparison with Facebook’s early “move fast and break things” mantra, as betting companies pour thousands of dollars into their fight for market share.

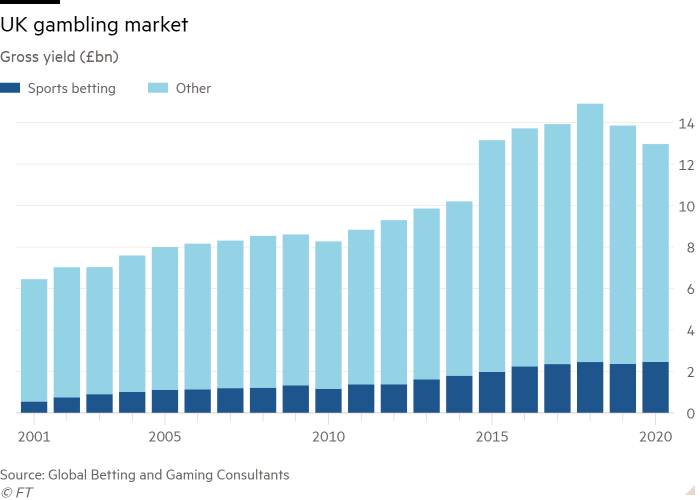

Keith Whyte, executive director of the National Council for Problem Gambling, warns that operators could find themselves facing stricter regulation as in the UK, where rapid growth following a loosening of betting legislation in 2005 resulted in fears of a spike in gambling addiction and a clampdown on the industry.

“[It’s] the million dollar question in our market,” he says. “Will there be a UK style backlash and if so, when?”

Winner takes it all

Almost half the US population — 154m people — watch sport on TV at least once a month, according to the research firm Statista. So the odds were always stacked in favour of the industry when the market for online sports betting was opened up.

But the proliferation of new wagering legislation also presents a potential boom to broadcast media seeking better ratings. Viewers of this year’s Super Bowl, traditionally the most-watched live broadcast in the US, fell to their lowest level in more than half a century, with 92m people tuning in, according to SportsMediaWatch. Yet the $500m in total wagered on the game that saw the Tampa Bay Buccaneers defeat the Kansas City Chiefs was up 70 per cent from 2020, according to the AGA.

Of particular interest to US media companies and sports leagues looking to drive engagement are in-game wagers — bets placed on events within a match, rather than its outcome. In-game betting comprised just 10 per cent of the US market as of January, compared with 75 per cent in the UK, according to Macquarie, but it is growing fast as broadcasters in some data-rich sports, such as golf and basketball, begin to tailor their programming.

The appetite to capitalise on the rise of in-game betting means that few weeks have passed this year without a partnership or sponsorship deal being announced between a gambling company and a sports team, league or media business.

Prior to the Supreme Court ruling, the major professional leagues, as well as the national collegiate sports governing body, were vociferous opponents of gambling, even taking the state of New Jersey to court over it in 2012.

Yet the leagues are now scrambling to get a share of the business: the National Basketball Association has begun producing alternative streams of some games to cater specifically for betting audiences and has also signed contracts with 30 sports betting companies to license its data and offer gambling platforms. Among clubs in the National Football League — the most-watched sport in the US — 11 have signed similar deals.

Among the most active dealmakers have been legacy casino companies wanting to buy sports betting technology and European operators desperate for access to the US.

Ramy Ibrahim, managing director at investment bank Moelis & Company, says he has completed more than a dozen mergers and media partnerships within sports gambling since the Supreme Court ruling, and says he has “a robust pipeline” of further deals.

This flurry of activity, Ibrahim says, is a direct result of the opening of the US sports betting market providing a boon to virtually every company involved from the media groups who now have “people tuning into a crappy game on a Thursday”, and the sports leagues reliant on broadcast revenues, to the growth-seeking gaming operators and impecunious state governments.

“If you allow people to bet on a game on this thing”, he says, pointing to his mobile phone, “you can generate revenue and everybody wins.”

$7.8bn

In online US sports bets wagered in the first two months of 2021 providing revenues of $576m to operators

$150bn

Was bet annually in the black market and offshore sites before 2018 says the American Gaming Association

1.4m

Gambling addicts identified in the UK although experts caution that the numbers are difficult to calculate

Dealmaking bonanza

Among the most notable deals have been the Las Vegas casino giant Caesars’ £2.9bn takeover of the UK bookmaker William Hill, which is due to complete this month. While in March, Bally’s, a Rhode Island-based casino company, said it had agreed “key terms” of a £2bn deal to buy the British online gambling company Gamesys.

Entain, owner of Ladbrokes and Bwin.party, fought off a takeover offer from the casino group MGM — its US joint venture partner — in January claiming that the £8bn offer “significantly undervalued” the business — largely due to the sky-high valuations of any operator with US exposure.

Penn National, the casino company that bought the sports and pop culture website Barstool, has seen its share price rise around 240 per cent since the acquisition, while Flutter — having seen rival online betting and fantasy sports company DraftKings almost quadruple its market value to around $23bn since it listed in April 2020 — is considering spinning off and listing a part of FanDuel.

Itai Pazner, chief executive of online gambling company 888, which is sitting on a £190m cash pile, says that he would like to secure a US deal but “you can’t buy anything because everything is [too] expensive. I would love to buy something there but everything is full, full price.”

The rush to be first into states as they regulate sports and online betting has also pushed up operating costs and resulted in a land grab for market share. Free bets and bonus offers abound as do swaths of adverts across traditional broadcast media, radio and billboards. DraftKings said in an investor presentation that in the first half of 2019 its cost of acquiring new customers was $471 per gambler, although chief executive Jason Robins says that it has since come down.

Summing up the frenzy, a second industry banker says that “everyone is scrambling around trying to devise a US strategy”, adding, “only three or four players are going to make money because it’s such an aggressive environment.”

Lessons from the UK

Many of the operators are UK-based businesses. And the US is a stark contrast to their home market where profits are being squeezed by tighter restrictions on the industry.

The sector’s rapid growth after UK betting laws were eased in 2005 resulted in a vehement reaction against gambling amid concerns about increased addiction and reports of betting companies exploiting vulnerable individuals. Some surveys show an increase in problem gambling — one last year suggested that there could be as many as 1.4m addicted gamblers in the UK — but experts have urged caution because the numbers are notoriously difficult to calculate.

Betting adverts are now emblazoned with prominent warnings about gambling addiction — urging people to “gamble responsibly”. Betting with credit cards is banned and operators have agreed a moratorium on TV advertising during live sports broadcasts before 9pm. A fresh review of the country’s gambling laws is under way with campaigners calling for a cut in the stake permitted to play online slot games as well as bans on football shirt sponsorship, rules on how games can be designed and checks on what customers can afford to lose.

“It’s a strange world where you have the UK moving to a more regulated model and the US throwing open the doors,” says Darren Bailey, a sports lawyer at London-based Charles Russell Speechlys. “You think, what is going on?”

Robins says he looked to the more mature UK market when deciding how and when to confront problem gambling at DraftKings because “there’s a lot of great lessons to be learnt ».

DraftKings is working with states to develop procedures that prevent problem gamblers from jumping from one gaming platform to another if they are flagged by operators. “People who are problem gamers are not good long-term customers . . . It can create a stain on the whole industry, and it’s not in our business interest,” he says.

Flutter’s chief executive, Peter Jackson, exercises the long held industry argument that if you regulate gambling companies too strictly, operators will not offer competitive odds pushing consumers to gamble on unregulated black market offshore websites. The American Gaming Association estimates that before 2018, gamblers annually bet $150bn on the black market.

But Whyte says that in their rush to attract betting companies to their states, some US legislators have been willing to ignore the lessons of the UK and other increasingly strict European markets. “State governments don’t want to know. They were desperate for money even before the pandemic and they see problem gambling as an inconvenient truth in their quest for taxes.”

He adds that since New Jersey permitted sports betting in 2018, the state — one of the few to monitor such things — has reported an increase in problem gambling to three times the national average.

Pazner of UK-listed 888 says a crackdown in the US is inevitable: “The regulatory backlash happens in every [market].” But Bill Hornbuckle, chief executive of MGM, says that operators have too much at stake to make a mistake. The key will be limiting the number of licences issued, he adds.

Other hurdles remain to the rapid growth of the sector. One is the speed with which state lawmakers push through gambling legislation. GamblingCompliance, the industry research firm, estimates that up to 11 additional states could pass sports betting legislation by the end of this year. The eyes of the operators are focused on states with large populations such as California and Florida yet both have strong Native American lobbies, many of whom own bricks and mortar casinos that they fear would have their trade cannibalised should online betting be allowed. A 1961 law known as the Wire Act currently prevents remote gambling across state lines.

The other factor is the ability of companies to plough money into the high stakes market. Flutter spent £350m on sales and marketing in the US alone last year, says Jackson. Hornbuckle similarly says that he expects to sink between $400m and $500m into BetMGM “before we turn an investment that is profitable”. He is also on the lookout for a media company that will buy into the business and, analysts suggest, a second bid is likely for MGM’s joint venture partner Entain.

But none of those aspirations will come cheap, he concludes: “It is becoming clear to me that [in the end] there will be four or five players in this space because the costs are not for the faint hearted.”