Militias, corruption and Covid: Rio de Janeiro’s deepening crisis

Alice Pamplona da Silva celebrated her fifth birthday last year the way a child should. Her parents presented her with cake and muffins, each bedecked in luminous icing and cut-out images of the Little Mermaid. Her hair tied in long braids, Alice beams at the family photographer.

By the first minutes of the new year, Alice would be dead, hit in the neck by a stray bullet as she watched the fireworks over Rio de Janeiro from her home in a poor hillside community close to the city centre. Locals say Alice was in her mother’s lap when the bullet pierced her body.

Last year one child was killed in Rio on average every month by stray bullets. Even since the death of Alice, another five-year-old — Ana Clara Machado — has been killed by a bala perdida — or lost bullet. The vast majority of the thousands of murders in Rio every year go unsolved and unpunished.

Brazil is reeling from overlapping crises. The economy has barely grown for almost a decade, held back by the collapse of the commodities boom and persistent mismanagement. And that was before the coronavirus pandemic created both the health emergency and a deep recession, to which President Jair Bolsonaro’s government is struggling to find a coherent response. Rio was among a number of Brazil’s big cities to announce last week various degrees of lockdowns as hospitals reach near full capacity.

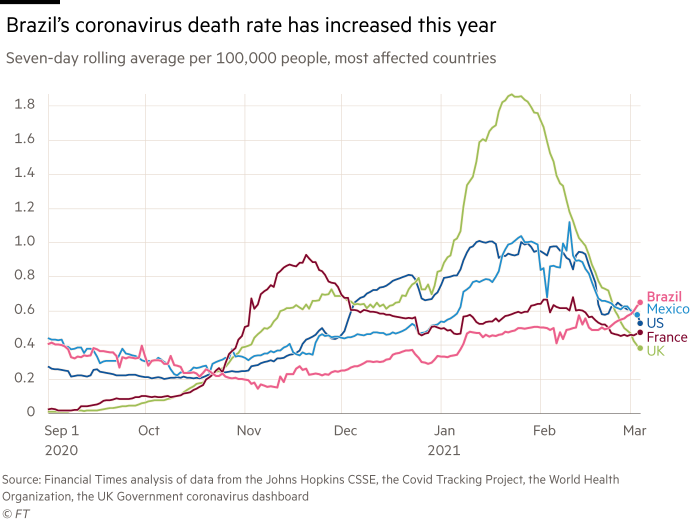

With one of the more virulent variants of the virus spreading rapidly in Brazil, many countries have in effect closed off travel to the Latin American nation.

The sense of malaise in Brazil is nowhere more keenly felt than in Rio, where both the city of 6.7m and the state that shares the same name are facing a profound crisis.

Known affectionately by residents as Cidade Maravilhosa (the Wonderful City), Rio, with its sandy beaches and lush peaks, has long been the iconic image of Brazil — the host of the 2014 World Cup final and the 2016 Olympics.

But for large chunks of the population — especially those who live in poorer communities — Rio is failing.

This is exemplified by the state’s epidemic of violence and, more specifically, by its inability to prevent children like Alice being caught in the crossfire. But the rot goes deeper. According to a new study, almost 60 per cent of the city is now controlled by so-called militias — mafia-style organised crime outfits that control entry into neighbourhoods, run extortion and drugs rackets and are increasingly moving into construction and other mainstream business lines.

Their influence over an estimated 2m residents has become so pronounced that even the authorities have begun to acknowledge that swaths of the state are no longer in their control. Fewer officials, however, are willing to acknowledge the militia’s ties with city and state politicians — an alliance that has allowed the rot to fester and spread.

“The state has failed. It has been failing bitterly. This postcard city of Brazil is built on a foundation of inequality,” says Lucas Loubeck of Rio de Paz, a group working to reduce violence in the favelas.

Economically, too, Rio is suffering. The heady days of Brazil’s commodities boom in the first decade of the millennium ended with a thud. A bruising recession five years ago has left the state’s coffers empty. Long an economic motor, tourism, too, has collapsed, buffeted on each side by Covid-19 and the city’s reputation for crime. More than 32 per cent of the city’s youth aged between 18 and 24 are unemployed, according to city officials.

“Preventing crime requires education, housing, employment. If you have that, you reduce the chance that a boy will migrate to crime. But there has not been that kind of thinking in public policy in decades,” says Loubeck.

Rio’s ability to respond to these problems has not been helped by a long history of corruption. Wilson Witzel, the current state governor, has been suspended over allegations of embezzlement of Covid relief funds. Three of Rio’s four previous governors are in jail or have served time.

“Rio is a ticking time-bomb,” says Michel Silva, a community leader in Rocinha, Rio’s biggest favela — the name used for poor neighbourhoods that have low-quality housing and weak property rights — which is home to more than 100,000.

From the raging urban war between drug gangs, militias and the heavily militarised local police to crises with the water supply, coronavirus and corruption at the highest levels of governance, Silva says life in Rio has become an increasingly precarious affair.

“Although the favelas have state law, the law is not applied in them. The state abandoned the favelas from the moment they emerged.”

‘Countless violations’

Many Rio favelas cling precariously to the hills and peaks that puncture the city’s skyline. Their construction began soon after the end of slavery in the late 19th century, when former slaves with little money needed somewhere to live. The unregulated, haphazardly-planned townships then swelled in the following decades as poor Brazilians from the country’s north-east moved to Rio in search of work.

When the federal capital moved to Brasília in 1960, taking with it tens of thousands of public sector jobs, Rio slipped into a long decline — a trajectory that has been broken only intermittently by cyclical spurts of growth in the oil, gas and iron ore industries. A large part of the country’s oil deposits lies off the Rio coast.

By the 1990s, the favelas were awash with crime as heavily armed drug gangs, such as the Red Command and the Third Pure Command, feuded violently for control over the city’s hillsides and mountain tops. The bloodletting triggered an aggressive police response, which continues today. It is referred to, almost blithely, as Rio’s “urban war”.

On one side, the police storm the favelas with helicopters and armoured vehicles; on the other, the gangs wield machine guns, grenades and sometimes — according to residents’ reports — human shields. Occasionally the traffickers succeed in shooting down the choppers.

“We have militarised police and armed drug traffickers and a scenario of urban war. And in the middle of all this, there are millions of residents,” says Loubeck.

Edmund Ruge, a volunteer in communities in the north of the city, says: “Most people know it is not an effective way to fight the drug trade. Yet it continues. It is the status quo. And there are long-running personal vendettas, so there is this back and forth in terms of revenge killings.”

Almost 94,000 citizens have been murdered in the state of Rio since 2003 when a new system for recording crimes began, according to official state data. The vast majority happened in poor communities. A study of the city of Rio de Janeiro, published late last year in the Police Journal, found that more than 50 per cent of homicides occurred in just 1.1 per cent of the urban space.

Justice is rarely served. A study by state prosecutors of 3,900 homicides committed in 2015 found that five years later, there had been no punishments issued for more than 3,500 of the cases. Killings by police, which reached a high of 1,800 — or five a day — in 2019, are also rarely investigated and are not included in official homicide figures.

“The police operations violate our rights to life, to housing, to be in the favela and to be in this city. There are countless violations that we suffer,” says Gizele Martins, a resident of the Maré neighbourhood.

The situation, however, is not without some hope. Last year, the number of homicides in the state dropped to 3,500 — from more than 5,300 in 2017 — an improvement that Rogério Figueredo de Lacerda, Rio’s police chief, attributes to better management of resources and a gradually improving economy from the sharp recession mid-decade. He also hails a decrease in vehicle and cargo theft.

“We are working with daily goals. And the numbers are favourable. They are still high, but the work is showing results,” he says. “Scholars like to say ‘the police go into the favelas only to foment war’. But we don’t want war. We want a peaceful community.”

Independent crime analysts and residents of the communities warn, however, that it is much too soon to draw conclusions about the recent decrease in crime. They say that a Supreme Court ruling banning police operations in the favelas during the pandemic — as well as the impact of the pandemic itself — were the driving factors rather than a profound change in Rio’s security landscape.

Ilona Szabó de Carvalho, executive director of the Igarapé Institute, a crime-focused think-tank, points out that while violent crime declined in the city, it increased in the rest of the state — a phenomenon reflecting the judicial decision to ban police operations in the city.

“To sustain the decrease, Rio needs to undergo structural changes” such as the professionalisation of the police force and the allocation of social support to needy communities, says Szabó, who left Rio last year amid fears for her personal safety. “It is very early to cry victory.”

The ‘Cidade Maravilhosa’ in numbers

60%

Proportion of the city now controlled by so-called militias. 550 militia members have been arrested since October, the acting governor says.

4.4%

Contraction in the state’s GDP last year, compared with 0.4% growth in São Paulo. The unemployment rate for 18-24 year olds in Rio de Janeiro is 32%

3,500

Murders in Rio state in 2020, a reduction from more than 5,300 in 2017. Over 50% of homicides occur in just 1.1 per cent of the urban space, one study found

‘The militia is the state’

If observers are split over the trajectory of violent crime, they are unanimous on the threat posed by the spread of the militias.

“We cannot deny the expansion of militias. It is a scenario in which we have had few great victories,” says Col Figueredo, who says these groups are often harder to tackle because they typically rely on the implicit threat of force.

According to the study last year by two universities, almost 60 per cent of the city of Rio and more than 20 per cent of the greater metropolitan area is now controlled by these mafia syndicates, which are sometimes composed of former police officers who maintain close links with law enforcement and have awareness of police intelligence.

They initially began as extortion rackets, but have since moved into drugs and arms-trafficking and ostensibly legal avenues such as construction and transportation, which can be used to launder criminal proceeds. Crucially, the groups — commonly associated with Rio’s west zone — also control entry and exit to the areas they control.

“The militias are not a parallel power; they are not groups that operate in the absence of the state. The militia is the state,” says José Cláudio Souza of the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, who has studied the militias over two decades.

In the favelas, some locals quietly suggest a preference for the drug gangs over militias because at least the traffickers are not engaged in systematic extortion.

“We used to receive reports mostly on drug crime but now the clamour is all about the militias. The reports are now always like this: ‘For the love of god, we no longer know who to count on,’” says Zeca Borges, founder of Disque Denúncia, a hotline to report crimes.

“It is not even a question of violence. People pay militiamen and the traffickers because there is no other way. The city is just beaten, it is broken.”

The militias have infiltrated local power structures, including city councils and the state legislature, say researchers. “It is all interlinked: militias, police and political power,” says Szabó. “It starts on the campaign trail: to do a campaign in a militia area, you need to be authorised. You need to negotiate whether a candidate can actively enter an area.”

“Once you do this, you are then linked to them and you have to take care of their interests while in power, which means less oversight and less messing around in their businesses, which are vast today.”

Reviving Rio

From his office in Rio’s neoclassical Guanabara Palace, acting governor Cláudio Castro, who assumed duties in August when Witzel was removed from office pending investigation, can afford to acknowledge the extent of his state’s problems.

“We are focused on cleaning house,” he says, outlining a new “intelligence-led” approach to tackle the militias by choking them financially. He says 550 militia members have been arrested since October.

But the governor must also focus on Rio’s crippling economic situation, which few doubt has spurred the city’s crime epidemic.

The state has been practically bankrupt since the commodities crash in 2015 — an event that itself was exacerbated by the years-long theft of public assets by politicians and businesspeople, a scheme revealed in the massive Lava Jato (Car Wash) graft probe.

The state’s gross domestic product is forecast to have shrunk 4.4 per cent last year, slightly above the 4.1 per cent national rate and considerably worse than neighbouring São Paulo — an industrial hub — that grew 0.4 per cent. In the third quarter of last year, the unemployment level in Rio was almost 5 percentage points higher than the national average.

The state must also contend with a painful legacy of debt, which diverts much needed funds away from public services, most notably hospitals and Covid relief. The state reported debt of R$165bn ($29bn) in 2019, up from R$153bn the previous year and amounting to more than 280 per cent of revenue.

“In Rio, inequality kills. This number of people aren’t dying because of coronavirus variants or the severity of Covid-19 — they are dying because they do not have access to healthcare, even though the city has one of the larger public networks in Brazil,” Lígia Bahia, a public health expert, told local media last month.

With the hospital occupancy rate approaching almost 80 per cent in the city, Rio on Saturday implemented fresh restrictions on the opening hours of bars and restaurants.

Castro believes that a revival of Rio’s fortunes can be driven by fossil fuels — oil and gas are the state’s “main vocation”, he says.

However, the long-term prospects for the oil sector have not been helped by Bolsonaro’s decision last month to fire the head of state oil company Petrobras when he refused to reduce oil prices paid by consumers.

Marco Cavalcanti, an economist at the Institute of Applied Economic Research in Rio, says that in the short term “the fiscal crisis requires the adoption of harsh adjustment measures”. But he adds: “Over the next decade we expect oil and gas production to increase significantly, which will provide significant revenue to the state through royalties.”

If those changes can occur alongside improvements in the level of corruption and crime, Cavalcanti — a former official at Brazil’s finance ministry — believes Rio’s economic prospects in the medium to long term are “relatively good”.

“It is a big if, of course,” he adds.

Loubeck, the social worker in Rio’s North Zone, has a more blunt assessment, highlighting the “ocean” of unemployed people in the city’s favelas. “The state is negligent in this scenario and is therefore responsible. The state has completely failed.”

Additional reporting by Leonardo Coelho and Carolina Pulice