Landlords face fresh dilemmas amid the economic storm

Sarah Quinlan is calling time on her role as a buy-to-let landlord. After building a portfolio of 16 homes across London and Suffolk from the 1990s, the former City professional has sold half and intends to sell down the rest.

The Covid pandemic threw her property finances into disarray when some of her tenants stopped paying rent, and she fears the coming economic storm will do the same, threatening the viability of the business.

“In the next six to 12 months, it’s only going to get riskier as people are going to be really stretched about what they can afford to pay in terms of energy and food costs. After that, if we’re lucky, they might be able to pay their rent,” says Suffolk-based Quinlan, 57.

She is one of a number of buy-to-let landlords who spoke to FT Money this week about their plans — in the pipeline or already under way — to sell some or all of their properties in the belief that the sombre UK outlook as well as an increased burden of tax and regulation have changed the economics of the private rented sector for individual investors.

Costs of all kinds are rising. As wholesale gas prices have soared, UK inflation has hit 10.1 per cent and was predicted this week to hit 18.6 per cent in January 2023, according to a forecast from Citigroup. Mortgage interest rates are climbing fast and many landlords are looking at big bills to pay for improvements needed for proposed new government energy efficiency standards.

But this is a debate with two sides. As demand for city living has swung back over the pandemic recovery, tenants are competing hard to secure homes in many places and rents are rising rapidly.

Some investors see this as a ripe opportunity to expand their portfolio and profit from long term demand, however unappealing the short-term economic outlook. Half (49 per cent) of professional landlords (those with four or more rental properties) intend to buy more homes over the next 12 months, according to a survey published this week by Handelsbanken.

As the UK heads into turbulence, FT Money explores the changing risks and rewards for buy-to-let landlords. Should they add or hold on to their assets in expectation of persistently high rents, or get out of the sector before the economy — and the circumstances of their tenants — puts their business at risk?

Rents are rising

One of those who sees a secure future for buy-to-let is Christopher Lloyd, 29, a London-based academic. In June he bought a three-bed flat conversion in Richmond as a rental investment, taking out a 5-year fixed-rate mortgage on the home.

He is unfazed by the uncertain prospects for incomes and employment, and the impact of high inflation on interest rates and the cost of living. In his view, what happens over the next two years is much less relevant than what happens over the next 20.

“For me, this is a long-term thing, something I’m going to keep hopefully for maybe a few decades. I don’t really want cash at the moment with inflation being so high. Like most people I like the security of having it in bricks and mortar. Where else are you going to put your money?”

His instincts have so far been borne out by a steep rise in demand for rental homes, after businesses and other organisations got back on their feet following the pandemic closures and lockdowns and workers returned to cities.

This has coincided with a shortage of new stock available to rent: Propertymark, a trade body for letting and estate agents, this week said an average of 127 new tenants had registered with each UK letting agency branch in July, compared with an average 11 new properties appearing on each branch’s books over the same period. Lloyd, who envisaged his flat appealing to young family tenants, rented it out immediately on completion of the purchase.

Rents have bounced back after dropping during the pandemic, growing by 9.5 per cent in the year to July across the UK and by 13.6 per cent in London, according to research group Dataloft and landlord insurance provider HomeLet. Yields — the income a rental home generates as a proportion of its value and an indicator of an investment’s attractiveness — have yet to tick up substantially as house prices have risen almost as fast as rents.

The exception is London, where gross yields have moved from 3.9 per cent to 4.2 per cent over the past year, according to research by property site Zoopla. But though yields elsewhere are static, less expensive housing outside the capital mean they remain much higher, at 6.9 per cent in north-east England or 5.9 per cent in the north-west.

Tenant groups and charities report an increasing incidence of applicants bidding over the rental asking price to win out against rival tenants. One landlord told FT Money he had been offered a year’s rent in advance by a tenant looking to secure the home.

Neal Hudson, director of market research company Residential Analysts, believes the relative shortage of rental homes is driven partly by more tenants remaining in their current properties and accepting rent increases, for fear of higher rents being demanded if they were to move elsewhere.

“A lot of landlords are taking the opportunity to ask for a bit of a rent increase from existing tenants. They don’t have to worry about voids or who the new tenant is — they’re just sticking with who they’ve got. So there’s a lot less property hitting the market,” Hudson says. Nearly three-quarters of letting agents said they had seen a rising number of tenants choosing to renew their tenancies over the past 12 months, Propertymark found.

Hitting the affordability buffers

The “million-dollar question” for landlords asking for rent rises, says Lucian Cook, residential research director at estate agent Savills, is at what point they will hit the limits of their tenants’ affordability — particularly as inflation bites.

“You have some very strong competing forces in the market at the moment. People have returned to cities, which fuelled this very strong level of rental growth. We have a situation where people have this ongoing need to rent, but how much more of their income will they spend to meet that? At some point the affordability constraints will start to weigh on rental growth.”

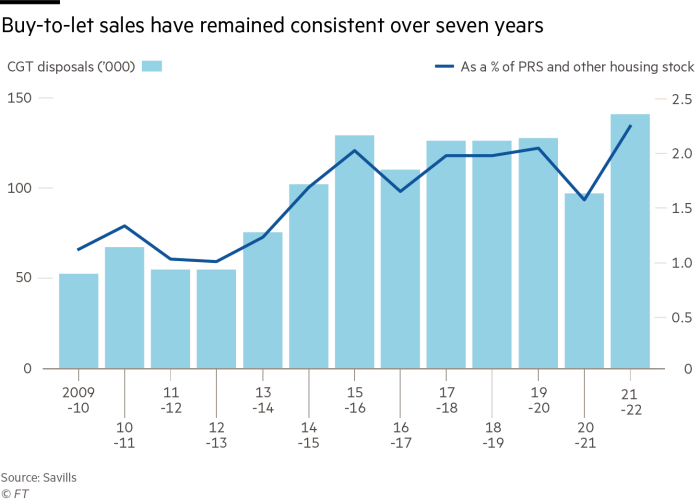

A major sell-off of buy-to-let homes has yet to emerge in the data. Capital gains tax on buy-to-let and second homes, which must now be declared and paid within 60 days of completion, provides an indication of shifts in the market. After rising in 2013-14, CGT on homes suggests sales of investment properties have remained at a consistent level on average over the past seven years, taking into account a pandemic dip.

“We haven’t seen an identifiable pick-up from those landlords who have said — ‘You know what? It’s going to become more difficult’,” says Cook.

Many landlords, particularly those who have held properties during the past decade or two of house price rises, have a considerable buffer of equity which helps them either postpone an immediate decision or choose to weather the storm, he adds. Selling up may also incur a large capital gains bill, at 28 per cent for higher rate taxpayers.

According to Savills analysis, older landlords dominate in the sector, with 69 per cent of private rented property owned by over-55s. And of the £450bn in housing value held by those aged 55-64, only about £100bn is mortgaged.

“There are a lot of landlords with accumulated housing wealth who have got relatively low levels of debt, which means they are somewhat insulated against interest rate rises. For these people, there just isn’t the same urgency,” Cook says.

Pressure points

Even among those with a large cushion of equity in their housing portfolio, however, many are disconcerted at the effects of a series of tax and regulatory changes on their finances and their ability to carry on a viable rental business. This — as well as the economic outlook — is causing a reassessment of their commitment to the sector.

Anoop Rattan, 55, a financial services professional based in west London, says he has been lucky over the years to have been able to take enough equity out of his rental property, a two-bed home in Bethnal Green he bought in 1993 — to put down a deposit on his primary residence and pay for other family costs.

But when he was recently forecasting his net income he found his costs had risen sharply, including his mortgage payments and charges such as ground rent payable to the management company, buildings insurance and maintenance. “I’m worried that even though I get a good rental income, I won’t make any profit at all.”

For buy-to-let properties owned by individual landlords — not held in a limited company — owners are no longer able to offset their mortgage interest payments against rental income to determine their taxable profit. From 2017, this major shift in policy has been blamed by mortgaged landlords for a big reduction in profits. It followed on the heels of a stamp duty surcharge of 3 per cent on buy-to-let and second homes introduced in 2016, which also chipped away at yields.

The drive for energy efficiency

While these policies left untouched those landlords without mortgages or ambitions to buy, a new rule change is set to land rental investors of many different kinds with hefty bills. Under government proposals on energy efficiency, planned for new or renewed tenancies by 2025, it will no longer be legal to let homes ranked below the most efficient A, B or C energy performance classes.

Retrofitting Britain’s ageing housing stock is a huge challenge and a common source of frustration for those who responded to a call by FT Money for landlords’ views on the outlook. The improvement work is one cost; research by mortgage broker Habito found raising a UK home from a D to a C rating will cost an average of £6,155. Another is having no rent-paying tenants while major work is done.

Rattan has paid for an assessment of steps he could take to improve the rating on his Bethnal Green flat. This produced two recommendations — but they only get him to a D rating.

“The government is saying that I can’t let this flat out if it’s not at C. What if I can’t reach that and I’m forced to sell? Then I would have to sell it, someone else would buy it — but the energy efficiency of the flat will not have changed.”

Whatever the outcome of the government proposals, landlords with inefficient buildings may face greater pressure to act as tenants see their energy bills soar.

“One thing is for sure,” says Cook. “When tenants are renting property, they are going to become much more acutely aware of the energy efficiency of the home and what their prospective energy costs will be.”

Richard Davies, managing director of estate agent Chestertons, warns that many landlord-investors appear unaware of forthcoming changes. “It’s not really on their radar,” he says.

New markets

Some investors are approaching the “buy or sell” question in a different way. Landlords have traditionally sought to buy second hand to avoid the premium associated with newly built homes. But James Ginley, technical director at property surveyor e.surv, points to growing demand among landlords for new-build properties, which are much more likely to pass the proposed energy efficiency rules. Yields are likely to be higher on these properties, he says.

“Is the rental market for new homes going to be stronger because of the energy story? Yes, quite probably. The rental population will be keener to pay a premium to offset their energy bills. So there’s a greater differential opening up in the rental market between new and old homes.”

Landlords are increasingly exploring other types of property investment. Chris Sykes, technical director at mortgage broker Private Finance, says more are turning away from the “broken” market for traditional single-let properties in favour of semi-commercial properties, developments, houses of multiple occupancy, such as student homes, or holiday lets. “More landlords are seeking out potential pockets of the market with higher yields,” he says.

The development market includes “build to rent”, in which a developer converts a property or builds one to include multiple units, which they let out rather than sell. Ben Sheriff, partner and head of London at mortgage broker Knight Frank Finance, says such activity has been on the rise, and he expects further growth given the opportunity for landlords to get better value by developing themselves.

“All of a sudden you’re seeing people that may have anywhere between five and 50 units starting to hold on to them,” he says.

Risks ahead

At present, market experts broadly agree that house prices will soften and probably fall next year, but are less likely to go into freefall given a shortage of stock and a base level of demand. Those factors may change. But landlords must also consider other risks related to the private rented sector.

Tenants receiving housing benefit or universal credit play a big role. According to the official English Housing Survey, more than a quarter (26 per cent) of private sector renters received housing benefit to help pay their rent in 2020-21 — 1.1mn households.

A deep recession would hit this part of the market hard, says Hudson. “I’m particularly nervous about the private rented sector where it is quite reliant on lower-income households — markets where they have lots of housing benefit tenants.”

As people are hit by inflation, they may look towards more affordable homes, leading to a “cascade” of moves across the country. But the most vulnerable, low-income households risk being squeezed out of all of their local rental markets with nowhere else to go. “Suddenly there’s a threat of rising homelessness and all the serious ramifications of a recession and an energy shock,” he says.

Landlords themselves are alive to the risks that come with recession and unemployment, as well as a market in which more prospective buyers find themselves priced out. For Quinlan, the Suffolk-based landlord, the costs of housing are now “mad” — and causing serious social problems — even as she acknowledges the benefit she has reaped from house price growth over 30 years.

“I know it’s easy to say this when you’re sitting on huge capital appreciation, but . . . if we don’t have workers who can afford to buy in London, we won’t have teachers and we won’t have nurses. We’re shooting ourselves in the foot.”

Are you facing difficulties managing your finances as the cost of living rises? Our consumer editor Claer Barrett and finance educator Tiffany ‘The Budgetnista’ Aliche discussed tips on the best ways to save and budget as prices across the globe increase in our latest IG Live. Watch it here.