Jack Grealish: England’s Golden Boy

The Wembley Stadium crowd was calling for him, yearning for him, long before it had seen him. The second half of England’s game with Germany had reached a deadlock. The English had not troubled Manuel Neuer’s goal for some time; the Germans had mustered a single shot, and then retreated into their shell. Stalemate had set in.

England had a wealth of talent on its bench to break it: Phil Foden, with his Gascoigne-blond hair, Manchester City’s great rising star. Jadon Sancho, coming off a devastating season in the Bundesliga. Manchester United’s spiritual leader, Marcus Rashford. The dynamic and industrious Mason Mount, a Champions League winner only a month ago.

England’s fans, though, wanted someone else. They wanted a player who would not even have been in contention for a place on the roster, let alone the team, had this tournament taken place, as scheduled, last summer. They wanted a player who had, at that point, only nine caps and precisely zero goals for his country.

They wanted a player who had never set foot in the Champions League, or even the Europa League, a player who had never won a cup or a league or a first-rate honor of any sort. They wanted a player whose greatest contribution to his national team to that point was a flick — admittedly, a brilliantly inventive one — in a defeat to Belgium late last year.

But despite all of that, the fans knew exactly whom they wanted. They started to sing his name, to demand that Gareth Southgate, the manager, summon him from the bench and send him into the thick of England’s biggest game since 2018 and its biggest game on home soil in 25 years.

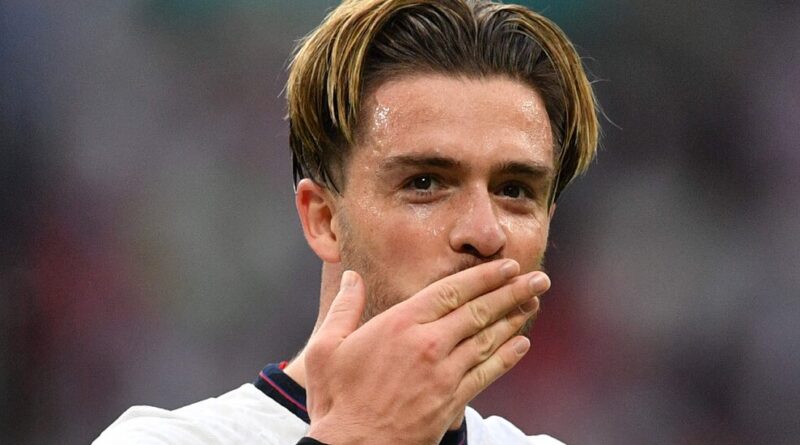

They wanted Jack Grealish, and nobody else.

England has spent a lot of time, over the last year or so, thinking about Grealish. At first, it was in the context of one of those classic English either/or debates, the sort of complex issue boiled down to a simple binary that fills all those quiet hours of radio and litters message boards and allows columnists to fulminate and encourages readers to click, click, click.

Should Southgate call up Grealish — the 25-year-old captain of Aston Villa, his boyhood team — or James Maddison, 24, the Leicester City playmaker with the slicked-back hair?

The answer, obviously, could have been both, or neither, or “well, they’re very different players and so this is a bit like asking whether England should play Harry Kane or a goalkeeper.” But that did not matter. What mattered was the question: Grealish, Maddison, either, or?

Southgate, not especially conveniently, settled that one a few weeks ago, when Grealish made his squad for Euro 2020 and Maddison did not. Smoothly, the debate shifted to acknowledge the updated circumstances. Grealish did not appear at all in England’s opening game against Croatia. Should Southgate be picking him? He was only a substitute against Scotland. Should he be starting? He was on the team against the Czech Republic. Should he not be the centerpiece of the side?

And then, 20 minutes or so into the second half of England’s round of 16 game with Germany on Tuesday, as Wembley was starting to fret about extra time and penalties and we all know how that ends against the Germans, the crowd made its verdict known. Pointedly, it started to chant Grealish’s name. It was not meant only as a paean for the player. It was an urgent, unanimous instruction for Southgate.

The England manager had all of that talent — Premier League winners and Champions League winners and stars from Manchester United and Chelsea and Manchester City — sitting on the bench. And yet it was Grealish, with his nine caps and no goals and no real experience in these situations, who the public had decided was the man for the job.

There is, as they say, a lot to unpack here. On one level, there is a very good reason that England — in the sense of its fans, its prominent cheerleaders and the public as a whole — has fallen so hard for Grealish: He is a very fine footballer, indeed.

In many ways, he is not a particularly English one. Or, rather, he is not the sort of player England has produced for a long time, since the heyday of all of those mercurial schemers in the 1970s. With his long hair and his rolled-down socks, Grealish evokes a player who is the antithesis of an English footballer: the Portuguese playmaker Rui Costa. Regular readers of this newsletter will know that, in these parts, there is no higher praise.

Grealish is graceful and strong and relentlessly inventive, among the most creative players in Europe, in fact. He shows for the ball, and he carries the ball, and he makes things happen. But the fact that the acclaim is not misplaced does not mean its pitch is not slightly unusual.

Grealish is good, but so are Rashford and Foden and Sancho. That, in the eyes of the public, they all now exist in Grealish’s shadow is a strange phenomenon, not one adequately explained by his abilities on the field.

Instead, it is hard to avoid the suspicion that part of the affection for Grealish comes not from what he does, but who he is, or what he seems to stand for. First and foremost, he passes the eye test: He looks like a good player. The fact that he is now wearing England’s No. 7 jersey is not the only echo of Beckham — there is the Alice band holding back his hair, too; his rolled-down socks suggest a consciousness of his own style.

More important, there is the fact that he looks like a player in a way that is recognizable to the fans. A few months ago, a video of four men in their 20s — all from Birmingham, Grealish’s hometown, as it happens — that had been manipulated to make the men look like they were singing a sea shanty (lockdown has been long and weird, hasn’t it?) went viral.

It is not an attempt to pass judgment on their look — musclebound, tattooed, some clothes too baggy, some clothes too tight, unnecessary glasses — to suggest that they were decked out in what is an instantly familiar uniform to anyone who has been out beyond 9 p.m. in a provincial British city in the last five years. It is not an attempt to pass judgment on Grealish to say that he looks like he might be friends with them. He has, in a very 21st century way, an Everyman quality.

That extends below the surface. Grealish plays for Aston Villa, his hometown club. He has had chances to leave but has stayed loyal (so far, at least). He has had missteps and invoked the ire of the tabloids more than once. He has attracted and warranted criticism, but his flaws make him a little more rounded than the image of the devoted, dedicated and ultimately quite boring superathlete that most of his peers cultivate. Fans can see themselves in Grealish. He is not perfect, but he is relatable.

More important than all of that is the simple fact that Grealish, compared with much of the England squad, is fresh. He is, to some extent, a blank slate.

Fans have watched Harry Kane and Rashford and Raheem Sterling for years. What they offer, the things that they can do, the things that make them special, are all well known. But so, too, are the things they cannot do, the flaws in their game. They have all been scrutinized to their very souls. The country knows, or at least thinks it knows, every single one of their shortcomings.

That does not apply to Grealish. Until relatively recently, most fans would only ever have seen him in highlights. Even over the last year, when every game has been televised, the vast majority will not have tuned in religiously to see Aston Villa play. To most, then, Grealish still has a box-fresh air.

That he has not played in the Champions League is, in that sense, an advantage, too. Not only does it mean he is immune to the tribalism that envelops England’s superpowers — fans of Manchester United and Manchester City alike will not feel dirty for wishing an Aston Villa player well — he has not had to cope with the exposure that comes with playing at the very highest level, for the biggest clubs and in the biggest games.

He has not been subjected to microscopic analysis after a disappointing performance against Bayern Munich. He has not endured a rough evening at the hands of Paris St.-Germain. He has not suffered in comparison to Lionel Messi. His limitations have not yet seeped into the national consciousness. England is not yet at the stage where it focuses more on what he can’t do than what he can.

And so, in the middle of England’s biggest game in years, as a country’s whole summer hung on a knife-edge, the Wembley crowd chanted his name, demanded the introduction of its new, unsullied favorite, the player still imbued with that magic of the new.

As he stood up on the substitutes’ bench to put his jersey on, the stadium roared. Here was the golden boy, to save the day. A few minutes later, Grealish slipped the ball into the path of Luke Shaw. He crossed, and Sterling tapped in. Not long after that, Grealish swung a cross onto Kane’s head, no more than 5 yards from goal. When he, too, turned it into the goal, Wembley exulted again.

Neither moment was a spectacular intervention, in truth — a simple pass, an easy cross — but both were taken as proof of the wisdom of the crowd. Grealish makes things happen. Grealish can do anything. Grealish, England’s great summer love affair, is fresh and new and perfect. For now, at least. But for now may be all that matters.

The Copa Curse May Yet Lift

After 1,800 minutes, plus injury time, spread across 20 games and four cities, the Copa América has succeeded in eliminating only Bolivia and Venezuela. Two weeks in, it is possible to feel that a competition that seemed destined not to happen — it was moved from Colombia and then Argentina to Brazil, ravaged by the pandemic — has still not actually started.

Things should, in theory, start to improve from here. The story of the group phase (as is the case every year, and we mean every year, so often do they insist on playing it) has been trying to work out which of Brazil and Argentina is best placed to win it, and which team represents the most likely challenge to that duopoly.

The answers, so far, are a little indistinct. Argentina and Brazil sailed through their groups, dropping points only at the start (Argentina) or at the end (Brazil). The former has Lionel Messi in a determined mood; the latter has the more balanced side, and home-field advantage.

It is, certainly, hard to see Brazil not making the final. Chile, its opponent in a quarterfinal on Friday, started and sputtered in the group phase. The semifinals will bring an encounter with Peru or Paraguay. Argentina’s path is more challenging. A young Ecuador team held Brazil to a draw in its last group game and has a handful of highly promising players scattered throughout its ranks. Uruguay, likely to await in the semifinals, is all gnarled experience.

Messi has suggested he is in the sort of mood that might single-handedly propel his team to the final in Rio de Janeiro on July 10. That should, in theory, bring Brazil into his path, as he tries to end his long wait for an international honor before his time runs out. It has been a long road here. That denouement may just about be worth it.

The Greatest Day of Them All. Maybe.

Unai Simón’s week might have been very different. He might have spent the last five days under the baleful glare of the world’s news media, a target for fury and pity in equal measure, absorbing the blame for Spain’s elimination from Euro 2020. Instead, his quite astonishing error — and the own goal it yielded minutes into his team’s round of 16 meeting with Croatia — had all but been forgotten within a few hours. How fortunate for Simón, really, that he happened to make his mistake right at the start of the most remarkable day of tournament soccer, well, ever.

That was certainly how it felt in the immediate aftermath of France’s defeat to Switzerland on penalties. All tournaments have days when they suddenly catch light, days that sweep you along with them, but as Kylian Mbappé trudged from the field, away from the scene of the greatest disappointment in his young career, it was hard to think of one that had packed in quite so much as this.

Or was that just the shock and emotion and recency bias talking? It is at times like these that Twitter’s hive-mind structure and its willfully contrarian nature come into their own. It is, in effect, a large group of people, all of whom are conditioned to tell you why you are wrong at any given moment.

The alternative suggestions duly flooded in. Most convincingly, Andrew Downie selected two dates from the 1970 World Cup: June 14, the day of all four quarterfinals, including West Germany’s win against England, and June 17, when Brazil beat Uruguay and Italy overcame West Germany in what became known as the Game of the Century.

Mike Martin nominated June 30, 1954 — the semifinals, West Germany beating Austria and Hungary dethroning the reigning champion, Uruguay, with 13 goals spread across two games. Davet Hyland went more modern, pointing to both quarterfinal days in 1994: the one with Brazil beating the Netherlands, 3-2, followed 24 hours later by the one with Bulgaria’s win against Germany.

All valid cases, and all worthy of consideration. I would, though, suggest that the suggestions from 1954 and 1970 fall short for one reason alone: All of those games were played simultaneously. It would not have been possible to watch, and to savor, them both (even, in the case of 1954, on the radio). They may well have been the greatest afternoons in tournament history, but they did not stretch out to occupy most of the day.

Which leaves 1994, and those sweltering, exciting days in Dallas and Foxborough, Mass., and East Rutherford, N.J., and Stanford, Calif. Whether one of those edges it for you over what happened on Monday may well be less to do with the quality of the drama on offer and more to do with how your mind works, whether the freshness of the recent outweighs the power of nostalgia. And that is entirely your call.

Correspondence

Plenty of thoughts on last week’s idea that it may be time for the European Championship to expand. It is fair to say, I think, that it split opinion (both in my inbox and on Twitter), with the balance edging toward a polite but firm no.

Dunstan Kesseler finds it hard to “get behind a tournament in which half of the teams in UEFA would qualify.” Mark Brophy pointed out, quite rightly, that awarding slots to Russia and the Czech Republic based on victories for the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia is problematic. Fayzan Bakhtiar believes that expanding the tournament would only “compound” the issue of players’ daunting workload.

There were plenty, too, who offered alternative ideas. Harry Richards wants to see the abolition of the round-robin format in the groups, instituting instead a hybrid group/knockout system. Stephen Gessner would cut the number of teams that progress from the groups, but then make them play a two-of-three series for qualification. Most convincingly, Tony Culotta thinks things might be improved by a 28-team tournament in which only two of the teams finishing third in their group reach the knockouts.

This is the glory of workshopping, of course. The format, as it exists in my head, has now been refined. There would be no places for historical merit, now; instead, the 16 teams we have seen competing in the first knockout round of this summer’s edition would be given a pass to the finals in 2024. That neatly circumvents the (incorrect) allegation that some countries would “not have to qualify.” They would, it’s just that it would already have happened.

The most convincing element of it, though, is the part that Charles Sutcliffe believes is flawed. The FIFA rankings — the metrics that define who goes into which qualifying group — proved unerringly accurate in predicting which teams would progress to the last 16, he wrote, rather neatly challenging the idea that they don’t work.

My response would be that this is precisely the problem: The countries with higher rankings, according to FIFA, get better qualifying draws, and so they are likely to proceed more comfortably, and therefore they are likely to get better seedings when the groups are drawn, allowing them to get to the round of 16 more easily. Even ignoring how easily the rankings can be gamed, and how they anchor teams to historical performance, it is this that is their greatest problem: They are essentially self-fulfilling. Breaking the spell they cast over international soccer would be the most significant consequence of changing the way the Euros work.