How to pay executives in the age of stakeholder capitalism

[ad_1]

On a web page setting out its views on everything from privacy to climate change, Amazon, the ecommerce company, states that diversity, equity and inclusion “are good for business — and more fundamentally, they’re simply right”. Such arguments are commonplace at large companies, yet there is one area where business leaders’ commitment to equity is less clear.

Andy Jassy, Amazon’s chief executive, earned nearly $213mn in 2021, much of it thanks to an award of restricted stock units that he can cash in over the next decade. At the same time, the median Amazon employee earned just under $33,000. A CEO pay ratio of 6,474:1 is unusual but Amazon is not the only company with a yawning gap between pronouncements on equity and the vast sums they pay their most senior managers.

Last year 94 per cent of US employers polled by Just Capital, a non-profit US research organisation, said their organisation had committed to greater workplace diversity, equity and inclusion. While this was happening, the average CEO in the top 350 US public companies by revenue earned 399 times more than a median employee, according to the Economic Policy Institute, whose calculations include estimates of the worth of granted shares when cashed in.

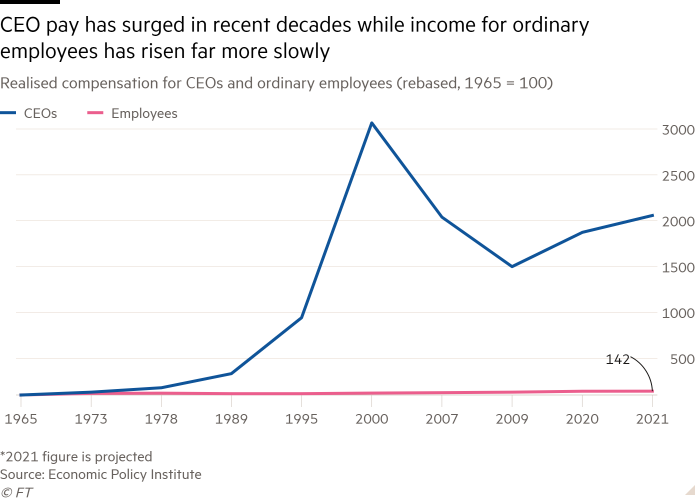

The growth rate in CEO pay in the US since 1978 is equally striking: a real-terms increase of 1,460 per cent compared with just over 18 per cent for average workers, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a non-partisan Washington think-tank.

The divergence between the rewards for senior managers and the pay of average workers troubles the readers of FT Moral Money. When we asked them if this was a concern, the universal response was “yes”. More than 80 per cent saw no advantage to the high level of executive pay.

Moral Money Forum

💾 View and download the entire report

🔎 Visit the Moral Money Forum hub for more from this series

Few markets match the sums that are paid in the US. In Nordic countries, for example, governance structures such as foundation ownership of companies have kept a lid on executive pay packages. The UK has broadly followed the US, albeit with sums that are less eye-popping. In 2022, boosted by record bonus payouts, the average total pay for FTSE 100 chief executives rose by 23 per cent to £3.9mn.

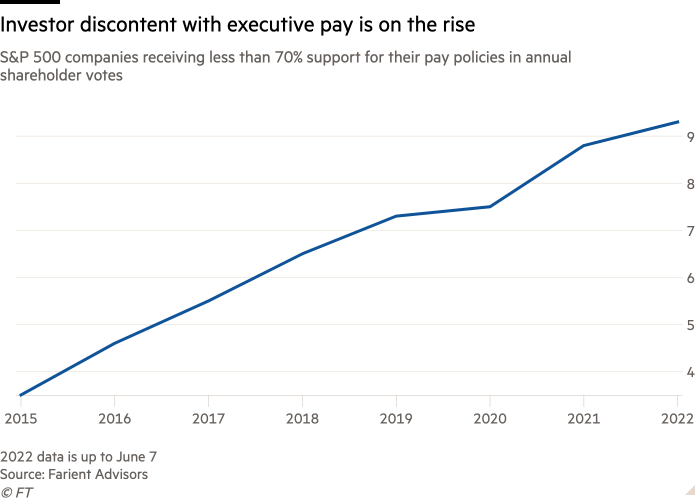

With records being set on a regular basis, investor unease over high salaries and bonuses shows up in say-on-pay votes. In 2011 the SEC forced US companies to put executive pay plans to a shareholder vote. Since then, it has been rare for any company to get less than 90 per cent support in a say-on-pay vote. Midway through the 2022 US proxy season, though, the percentage that failed to get even 70 per cent support had leapt from 3.6 per cent in 2015 to 9.3 per cent, according to Farient Advisors, the Los Angeles consultancy.

Some investors are going further. Shareholders in Tesla have taken the carmaker to court over the pay package awarded to Elon Musk, its chief executive, which is potentially worth $56bn, largely in share options.

The Tesla case reflects broader investor concern. London Business School found that 77 per cent of institutional investors in UK equities believe that chief executives’ pay is too high, and more than 80 per cent blame “ineffective” boards for not lowering it. Complaints vary: Farient found that other grievances included weak links between pay and performance, lack of transparency and the sheer size of compensation packages.

Soaring executive pay has also prompted resistance from another set of stakeholders — those who believe that business should play a role in shaping a fairer, more equitable society.

Abigail Disney, the entertainment heiress, has criticised the gap between the rewards given to Bob Iger, who has returned to Disney as chief executive, and the low pay of many workers at the company’s theme parks. “He deserves to be rewarded,” she told the Financial Times, “but if at the same company people are on food stamps and the company’s never been more profitable . . . how can you let people go home hungry?”.

Martin Whittaker, the founding chief executive of Just Capital, argues that bigger pay gaps risk a backlash from unions, workers and consumers. “If employees are sleeping in their cars and relying on food stamps, and you’re getting paid thousands of times more than median worker pay, that’s a risk,” he says. “At some point the chickens come home to roost.”

Asked what they considered the biggest risks of the widening pay gap, most Moral Money readers (71 per cent) agreed that high pay can leave executives detached from the concerns of employees and consumers. Almost half pointed to difficulties in employee disaffection and recruiting and retaining the best workers.

Unless executive pay packages include a requirement that equity must be held for a set time, loading rewards with stock can lead to the pursuit of short-term goals to boost the share price. That can conflict with the long-term strategies needed to contribute to a low-carbon economy or a more diverse workforce, which usually involve upfront costs.

“It’s not uncommon for a CEO to get paid based on how well their stock does either in absolute terms or relative to their competition,” says Sarah Williamson, chief executive of FCLTGlobal, a Boston think-tank that champions long-term investing. “That’s very short-term oriented, and that does not incorporate any of those sustainability issues.”

It also reinforces the mantra of shareholder primacy, argues Judy Samuelson, who founded the business and society programme at the Aspen Institute, based in Washington. “Paying people principally in stock is antithetical to the whole notion that the shareholder is by far not the most important person at the table, or at least is one of many stakeholders,” she says.

Nor is it necessarily a solution to tie part of the package to performance targets based on environmental, social and governance criteria. “You have to have a CEO who cares about these issues and knows how to deal with them,” says Lynn Paine, a professor at Harvard Business School, who writes on leadership and corporate governance. “The idea that 20 per cent of their bonus is going to change whether they care or not is highly unrealistic. If they don’t care about it, you’re not going to fix it with an incentive.”

As pay incentives continue to encourage short-term thinking and the earnings gap widens, ESG investors and others are asking with new urgency: How much is too much? Can pay packages be aligned more effectively with corporate goals on equality? And how can financial rewards be used to encourage long-term value creation and environmental sustainability?

How did we get here?

As unintended consequences go, it is hard to find any as spectacular as that caused by the US Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1993, which was meant to curb excessive executive pay. Introduced under President Bill Clinton, it limited corporate tax deductions for executive pay to $1mn a year per person.

The legislation exempted performance-based rewards and so had the opposite effect to that intended. One study found that between 1993 and 2003, packages paid by US public companies to their top five executives increased on average by 98 per cent, adjusting for inflation, as companies limited salary increases while stuffing executives’ packages with bonuses and stock options.

“Executive compensation started taking off significantly in 1993,” says Don Lowman, who leads the rewards and benefits business at Korn Ferry, the recruitment firm. “It was the biggest contributor to the increase in executive compensation of any single act.”

It also led to packages being heavily weighted towards equity, doing little to incentivise the long-term thinking needed to address sustainability challenges. “The executives have so much tied up in how the stock price performs, they’re inclined to do everything they can in the near term to make their numbers,” says Lowman.

Of course, a 30-year-old law cannot fully explain the soaring increases in executive pay in recent years. That is due to a mix of factors, from market failures to human psychology.

The spirit of competition is not to be underestimated. “Our brains get activated when we learn that we are better than others. It’s the way we’re wired,” says Camelia Kuhnen, professor of finance at Kenan-Flagler Business School, North Carolina. Kuhnen is an expert in neuroeconomics, behavioural finance and corporate finance. “People tend to fixate on this one dimension of success, which is: ‘I must make more than others’.”

One-upmanship is not limited to individuals. “No compensation committee wants to believe they only have an average player, so there is a tendency to chase this ever-increasing average and make sure they pay above the average,” says Lowman.

Alexander Pepper, a professor of management at the London School of Economics, sees this as a market failure that has done much to ratchet up pay for managers. “There isn’t a labour market to determine the price when it comes to very senior executives,” says Pepper. “Instead people just copy everyone else — the types of pay practices, the types of instruments used to pay people and the amounts that people pay.”

Bad for business

Even though commentators and activists like to rail at high salaries, reforming executive pay is a tough proposition. Compensation committees will grapple with making the right selection from the smorgasbord of cash, stocks and options, and worry over whether they have picked the right amount. Senior pay, though, is still only a fraction of operational costs — companies may feel they need not worry.

For similar reasons, most investors have traditionally given little thought to executive pay. As Pepper points out, for an investment manager whose 3 per cent stake in a company means managing billions in funds, it hardly matters whether the CEO is paid an extra $1mn. “Historically, institutional investors haven’t been interested in executive pay,” he says. “Investors say, ‘It’s small beer for us, so we’re not bothered.’”

This is starting to change. There is evidence that even before considering their effect on a company’s strategy, giant rewards are not necessarily good for the business itself.

This was the conclusion reached by As You Sow. Since 2015, the shareholder advocacy group has produced an annual list of “The 100 Most Overpaid CEOs” by correlating data on CEO pay with figures on total shareholder returns. According to this correlation, companies with the most overpaid CEOs have consistently fared worse financially than the average S&P 500 company. The cumulative underperformance was 20 percentage points.

Performance-related packages can even have negative consequences. “Some people are intrinsically motivated to, let’s say, put in more effort,” says Kuhnen. “And research shows that if you give such people high-powered incentives, where pay depends significantly on what is achieved, it works against intrinsic motivation — they lose their natural desire to do the right thing.”

Worse, substantial rewards can affect people’s judgment, argues Paine. “What’s not paid attention to is the effect an incredibly high payout has in nurturing the hubris that leads to reckless risk-taking,” she says. “It goes back to Icarus — when people have too much power, they lose touch with reality.”

When it comes to one significant operational expense — staff salaries — wage negotiations can be tough if union leaders baulk at increases that are tiny in comparison with those of bosses. This could be part of what has driven US sentiment in favour of trade unions to its highest point since 1965.

“There are many factors behind this,” says Aron Cramer, chief executive of BSR, a Washington consultancy that specialises in corporate social responsibility. “One of them has to be the sense that hourly workers and others can’t be secure about their futures, while the C-suite is doing extremely well.”

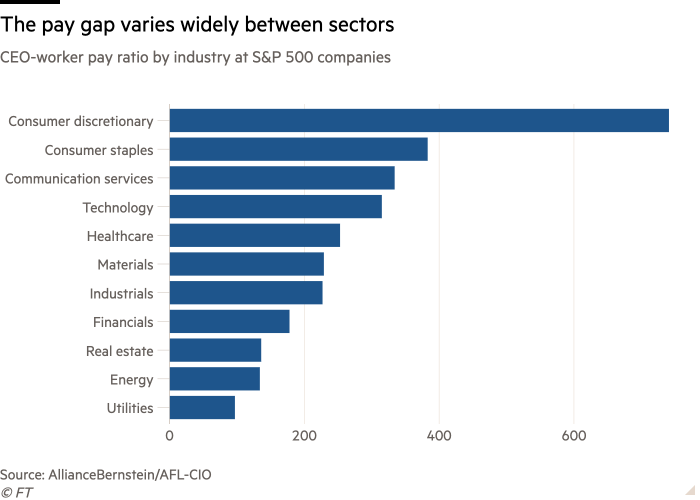

Unions are paying close attention to the discrepancy between CEO pay gains and worker wage increases. The AFL-CIO, a US federation of unions, traces these in Executive Paywatch, its annual report. With evidence that companies with strong unions tend to be more restrained on executive pay, especially before contract negotiations, it is possible that union pressure could restrain or even help reverse the trend towards high CEO remuneration.

One game changer could be an initiative at the world’s biggest asset manager. In November, BlackRock announced plans to open its Voting Choice programme to retail investors, which could give smaller investors more clout in proxy battles on corporate governance issues. “Voting Choice has the power to transform the relationship between asset owners and companies,” wrote Larry Fink, the chief executive of BlackRock, in a letter to clients and company CEOs.

If asset managers adopt this approach more broadly and everyone from pension holders to individual investors has a say on pay, companies may have to give more attention to how executives’ rewards are seen in the wider world.

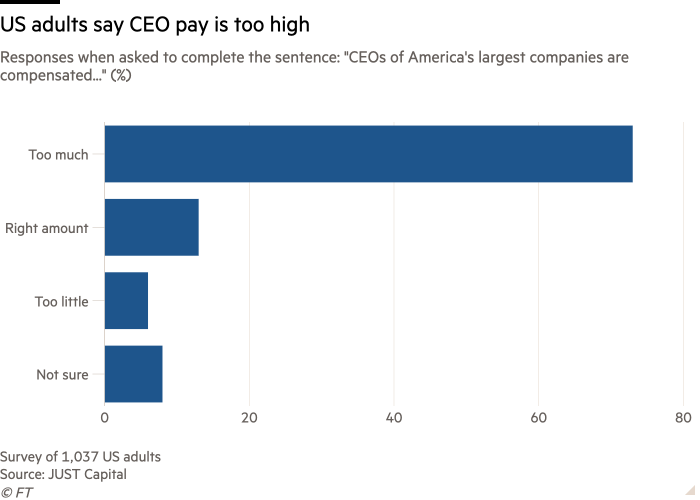

“Our polling shows that the vast majority of Americans, 87 per cent, think the growing worker-CEO pay gap is a problem, and that’s across the board,” says Whittaker of Just Capital. “You can ignore public opinion if you want, but public opinion says this is a problem.”

Are ESG-linked rewards the answer?

In addition to the sense that extremely high pay packages do not sit well with corporate proclamations on shared purpose, there is also the question of how they influence business progress (or lack of it) on ESG issues, such as climate change, resource efficiency, diversity and equality.

“The ability to make life-changing sums of money in a short period of time might create incentives to defer things that don’t directly lead to enhancing the stock price, and sadly [acting on] climate change is one of those,” says Tom Gosling, executive fellow at both the London Business School and the European Corporate Governance Institute.

“The behavioural science is pretty clear,” says Samuelson. “The brain doesn’t internalise long-term. Even if it says you’re not going to collect on the stock for six to 10 years out, or until you retire, it doesn’t translate that easily, so everybody is looking at the stock price.”

Given the difficulties of pinning back executive pay, a new approach is gaining momentum: connecting pay to performance on social and environmental goals. In fact, companies seem to be rushing to announce this strategy. The proportion of S&P 500 companies that link executive pay to ESG performance rose from 66 per cent in 2020 to 73 per cent last year, according to the Conference Board think-tank.

Some activists see this as an important change that could accelerate companies’ progress towards goals such as net zero emissions, and 71 per cent of FT Moral Money readers agree that executive pay should be linked to performance.

Some observers, however, (including many FT Moral Money readers) worry that the rapid take-up of ESG performance-linked pay will lead companies to set targets that are too vague, too easy to hit, not relevant to their business or that simply pay lip service to sustainability.

In its conversations with companies, the Conference Board found that many businesses thought tying incentives to ESG targets was only of medium importance in achieving their ESG objectives, says Paul Washington, executive director of the Conference Board’s ESG centre. “Often why they’re doing it is more of a signalling initiative to tell investors that they care about ESG.”

For their part, investors want to be sure that companies reward the right things over an appropriate time. As with their sustainability strategies, until companies figure out which social and environmental risks and opportunities really matter to their business, they cannot design appropriate incentives.

“Workforce health and safety in a bank is not as important as it is for an oil company, so first and foremost, there needs to be a linkage to what is material from an ESG perspective,” says Paula Luff, director of ESG research and engagement at DSC Meridian Capital, the credit investment firm. “The long-term commitments some companies are making really need to be in the long term incentive plan so there’s accountability over time.”

Another concern arises when, as in many companies, a portion of the bonus is based on ESG goals that are merely directional or not sufficiently challenging, says Washington. “What’s happened is you’ve taken a portion of the compensation that was truly performance based and made it easy to achieve,” he says. “That’s a real concern for investors.”

Gosling believes investors are right to worry about this. Research he is conducting with PwC, where he established and led the executive pay practice, shows that ESG targets are paying out to executives at higher rates than other targets. “This doesn’t seem to accord with where we are on climate change,” he says. “So there’s a real risk of low-quality implementation of ESG targets leading to more pay and not more ESG.”

With questions over how ESG is being integrated into senior pay schemes, investors are working harder to find exactly how companies factor sustainability into reward packages and whether they set sufficiently ambitious goals.

In a 2020 ESG engagement campaign, for example, AllianceBernstein, the asset manager, asked companies not only whether they included ESG metrics in their executive pay packages but also how they chose those metrics and whether at least one of them was material and measurable.

Amundi sees say-on-pay votes as one way to hold companies to account, says Caroline Le Meaux, head of ESG research, engagement and voting policy at the European asset manager. But conversations with managers are equally important.

“When we speak with companies, we want to know that ESG KPIs [key performance indicators] are in line with the strategies that the company has announced publicly,” she explains. “And year-on-year, we try to learn from experience and use engagement to make sure we are pushing companies to be more stringent.”

A more purposeful pay package

In 2020, the Aspen Institute and Korn Ferry published Modern Principles for Sensible and Effective Executive Pay. The five principles offer companies practical guidance, from reducing the focus on total shareholder return to ensuring packages are clearly written and free of jargon.

One of the principles is about increasing board accountability for rewards. Suggestions include having pay levels determined by an independent board committee, with outside advisers informing but not dictating decisions. All directors should understand the executive pay plan before approving it and the board should ensure that metrics and performance standards reflect business priorities.

Investors, meanwhile, have come up with pay principles of their own. Through its engagement campaign, AllianceBernstein identified best practices for incorporating ESG metrics into executive pay. For example, rather than creating a list of ESG metrics with each weighted at 1 per cent or less in determining performance-related pay, it recommends that companies select fewer metrics and give each a meaningful weight.

AllianceBernstein also suggests selecting the ESG issues that matter most to the business, developing ways to measure progress and using standalone ESG metrics (rather than including them in individual or strategic objectives). This makes it possible to see how each metric affects the final payout.

Gosling stresses the importance of focusing on material issues, being transparent and creating packages that are not complicated. He says: “Be bold enough to set a bit of ambition around the target. Don’t limit it to what you were planning to do anyway.”

In October, Legal and General Investment Management published its UK Principles on Executive Pay. The emphasis is also on simplicity, transparency and fairness. It stresses the need to use awards to promote long-term decision-making and to give boards the ability to use discretion and to ensure that final payments match the business’s long-term performance.

Some argue that companies can encourage long-term thinking by forcing executives to hold on to shares for years before cashing them in. Alex Edmans, a professor at London Business School, has argued that more investors favour CEO packages that take the form of a simple grant of equity, held for at least five years.

To make sure that the right ESG goals are put into the rewards system, the Conference Board recommends that companies adopt a wait-and-see approach. It suggests using ESG operating goals for a year or two, assessing how relevant they are for the business, and then developing management and employee buy-in, along with robust measurement and reporting tools. Only then, it says, should they become part of pay packages.

Given the time and effort this will require, the Conference Board has also suggested the creation of a steering committee made up of representatives from those parts of a business that shape financial and sustainability strategies. The committee should have full access to the data needed to measure and report on ESG performance.

When we asked FT Moral Money readers what changes to senior pay packages they thought would do most to advance corporate sustainability strategies, their suggestions ranged from limiting executive pay to a multiple of the lowest-paid employee, or increasing the length of vesting schedules, to ending stock-based pay altogether.

As companies, investors, compensation committees, governance experts and others grapple with how to redesign senior executive pay for an era of sustainable business and stakeholder capitalism, plenty of thought is being put into new structures, targets and timelines.

However, given the scale of some sustainability challenges, some question how much ESG-focused rewards systems can achieve. “Where we have an issue like climate, where there is a massive externality, you’re never going to do enough on pay to really address that,” says Gosling. “It’s like bringing a peashooter to a gunfight.”

Samuelson questions whether senior management should be given financial incentives for ESG challenges that they should already be paying attention to. “Do we really have to incentivise a CEO to be concerned about diversity and equity? Is that the appropriate way to get results?” she asks.

Washington agrees. “If you’re serious about achieving environmental and social impact, it matters more how you’re incorporating that into your products, services, procurement and operations,” he says. “This all goes much deeper than slapping a couple of ESG metrics into your annual incentive plan.”

Eyes on the prize

Even where linking ESG performance to pay is viewed as a sideshow, there is nevertheless a recognition that senior pay more broadly needs to reflect changing public attitudes towards fairness, equity and the role in society of companies — and by extension their senior managers.

Luff believes that if companies are to move away from short-term thinking and the mantra of shareholder primacy, they need to rethink executive pay. “The world has changed,” she says. “Shareholders are important stakeholders but companies are expected to have a purpose beyond that. Compensation packages need to reflect this expanded view.”

Samuelson is among those to call for a new approach. “We need to find executives who want to run their companies differently and who are thinking differently,” she says. “They can be well compensated but we need a real reset.”

Some argue that this reset needs to happen at every level of an organisation. “What people see as unfair is when some people benefit from the stock going way up and others get no benefit,” says Williamson. “People are increasingly thinking about how frontline workers could benefit from the growth of equity markets or from the success of the company in some way or other.”

Williamson’s observation could point to an opportunity. At a time when many corporations face the heat over the packages given to top executives, turning more of their employees into shareholders and letting workers at the low end of the pay scale share in their company’s success could offer a path to redemption. Extending their largesse to other employees through stock awards as well as cash packages could even deliver a double win for companies, boosting their image and perhaps their performance too.

Case study: Weir Group

In 2018, with public outrage growing at the pay packages and bonuses given to senior UK executives, Weir Group, a Scottish engineering company, made an unusual decision: it halved the top rate of equity awards for senior executives. Shareholders voted overwhelmingly in favour at the annual meeting.

The company’s long-term incentive plan (LTIP) was dropped in favour of a “restricted shares” scheme, by which executives relinquished the potential for large payouts in return for smaller, guaranteed sums that vested over a much longer period than is usual for LTIPs. The Weir plan delayed payouts for up to seven years.

One reason for the change was that setting targets for long-term bonuses is tough because much of the company’s performance relies on oil prices, which are volatile. The result, though, is a remuneration scheme that has shifted the time horizons of executive rewards. “They wanted something more predictable for employees but also with a long-term focus,” says Professor Lynn Paine of Harvard Business School, who wrote a case study on Weir’s pay reform.

“My experience on boards is that the types of structural change you get with significant sustainability goals won’t neatly fit into a three-year LTIP,” says Clare Chapman, chair of Weir’s remuneration committee. “If you have management chasing short-term vesting horizons, it undermines making those really long-term choices needed to meet sustainability goals.”

As well as making changes to the senior executive pay scheme, Weir made all employees shareholders through what it calls its Sharebuilder programme.

“This is as much about a mindset and how you grow a business that’s delivering to all its material stakeholders,” says Chapman, “who also co-chairs the steering group of the Purposeful Company, a management think-tank. “With every employee as a shareholder, it’s another way of reinforcing that we want everybody in the Weir Group to act like owners.”

She says senior managers support the programme, with low turnover among them since its introduction. Also, 90 per cent of shareholders have backed say-on-pay votes in the past two years. “Before, it was more external oil price driving it, as opposed to internal performance,” she says. “This is a scheme [executives] feel they can impact.”

An annual internal survey shows that Weir’s wider workforce is now more engaged, and this puts it into the top decile for its sector.

Chapman warns that Weir’s strategy might not be right for every company. “But there should be a lot more companies in the FTSE considering this,” she says. “If long-term sustainable performance really matters, then restricted stock is well worth a look.”

[ad_2]