As Gucci turns 100, creative director Alessandro Michele is leading the fashion industry toward a different future

It is a blue sky July afternoon in Florence — a day that exudes optimism, possibility and … relief. Italy was the first Western country to feel the brunt of the coronavirus pandemic. Businesses shuttered here. Manufacturing ceased. The population was locked down and allowed outside only for essential errands. That list thankfully included dog walking, and, as one newspaper noted, Italy’s hounds have been thoroughly exhausted.

In a country of 60 million people, more than 125,000 have succumbed to covid-19 by the time I arrive. But the worst appears to be over. The caseloads have declined; the vaccine is getting into arms. The city is open. Italians are once again tourists in their own land. You can also hear snippets of British and French accents in the piazzas, as well as bits of Dutch and, occasionally, the flat-footed vowels of Americans.

The city’s narrow streets sparkle in the summer sunshine, and a discreet black minivan — dispatched by Gucci to deliver me from the train station to a meeting at the company’s archives with creative director Alessandro Michele — zips over a bridge and across the Arno river. It weaves through a city that has the uncrowded postcard gloss of an earlier, less frenetic era.

Florence is where it all began for Gucci, where it was founded in 1921. And even though the company has blossomed into an exemplar of global greatness, Gucci’s roots are, quite literally, still here. The archives are newly organized in a refurbished 15th-century palazzo, which once served as the company’s factory. Before I speak to Michele, I want to take a tour — a way of reminding myself of Gucci’s past so that I can better understand why it seems so perfectly situated in the present.

Since Michele became creative director almost seven years ago, his collections have expressed the full breadth of who we are: she/her, he/him, they/them. Gucci is Harlem and Haiti, the Hamptons and Hollywood, Republicans and Democrats. The clothes challenge gender norms with menswear that’s effusively pretty. They upend the definition of female beauty as something dependent on youth; schoolgirl dresses share prominence alongside “Golden Girls” caftans.

In photographs, his clothes can look stodgy were it not for the quirky individuality and confidence of the models who wear them. Up close, the silks are graceful and delicate, the knits are feather soft. Everything and everyone collide: skateboarders, boardroom animals, rappers, glamour pusses and logo hounds. Gucci isn’t a reflection of the zeitgeist; it is the zeitgeist.

[Diversity in modeling is no longer simply a matter of race and ethnicity, size and age. It’s everything and anything.]

And then in April, Gucci’s aesthetic shifted. The collection that Michele dubbed Aria was an example of the brand’s ongoing evolution. Aria reflected a therapeutic detente between trauma and hope. Michele offered a vision that was quieter, more romantic and less chaotic than the one he has long championed. “Fashion must change because life is changing,” Michele says. His new collection delighted the eye with glitter and feathers but without neglecting a soulful need for ease, comfort and a human touch during a global health crisis. The clothes were eclectic without being self-consciously weird, which was an enormous shift because Michele has been fashion’s primary purveyor of openhearted weirdness. The magpie edited himself.

“The last show, Alessandro meant to create something different, to — I mean, I’m not going against what he did in the past — but to elevate the message and create something that is more of this time,” Marco Bizzarri, Gucci’s president and chief executive, says, adding: “When you experiment, you need to continue to experiment.”

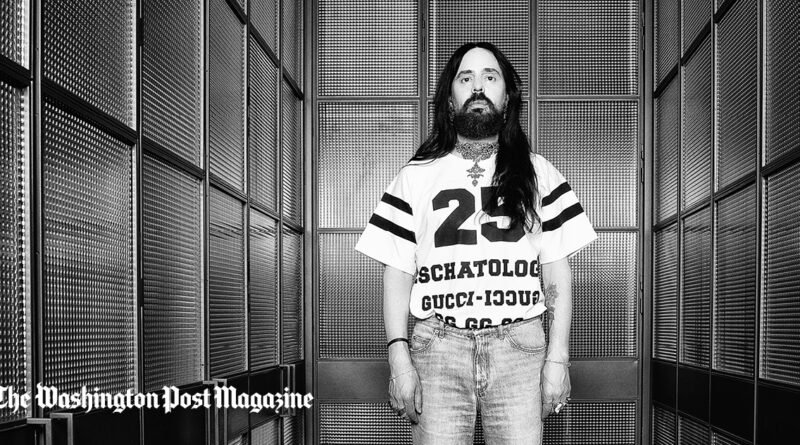

Alessandro Michele has been Gucci’s creative director since 2015.

Alessandro Michele has been Gucci’s creative director since 2015. Fashion changes because life changes. Aria made me curious to know more about what Michele was thinking. I wanted to know where fashion was headed. And if any brand had the capacity to be a harbinger of the future, it was Gucci. Upending the status quo is part of a pattern, part of Gucci’s history. Gucci has been able to say: This is it. This is what you’ve been desperate to buy; this is the aesthetic that perfectly expresses your mood, your sense of self. This is who we are at any given moment. “It’s like the brand is keeping the soul of now, ” Michele says.

This also happens to be a Gucci moment. The brand’s cultural endurance and continued relevance are plainer than ever. The company is celebrating its 100th anniversary, and its founding family’s ambition and treachery are the subject of the Ridley Scott film “House of Gucci,” which opens this month and stars Lady Gaga and Adam Driver.

During the height of the pandemic, the fashion industry used the quiet time to lament its operating practices: the relentless schedule of catwalk shows, the constant introduction of new collections, the globe-trotting. Video conference calls and open letters were devoted to promises to change — to slow down and produce less. Gucci is one of the few brands that actually made logistical shifts. And because it’s a multibillion-dollar, global entity, that vision and those changes can have a ripple effect.

So I came to Florence during a blissful lull in these tumultuous times to talk to Michele. Because getting a closer look at Gucci is akin to getting the long view of the fashion industry itself. If Gucci is selling anything, it’s the notion that fashion, culture and commerce all have the capacity not only to survive change, but to thrive in its aftermath.

Over the course of a century, the company has reinvented itself multiple times, arguably more often and more successfully than any other modern luxury house. It has been remade for baby boomers, Gen Xers and millennials.

The gentleman driver stops the minivan in front of the archives. And: this place. My God. The setting is as magnificent as one might imagine a Florentine palazzo to be. The elegant five-story building has graceful arched windows, soaring ceilings, dignified stone columns and remnants of 17th-century frescoes. A crystal chandelier the size of a Fiat 500 hangs from the center of a meeting room’s coffered, painted ceiling.

The ready-to-wear collection is protected by organza garment bags. Accessories sit inside custom glass vitrines that have handles shaped like scissors. Whole walls of shelves roll forward and back along brass tracks set into the floor. It’s as if you’ve entered a handsomely lit vault in which handbags are treated like gold bullion. Or, considering that one of Gucci’s python totes costs $5,800, it may be more accurate to say that banks treat gold bullion like designer handbags.

There’s even a jewel box of a room dedicated to the one-of-a-kind fairy-tale ensembles worn by celebrities such as Florence Welch. Each glittering gown or bedazzled cloak hangs on a dress form that stands upright in its own little pink padded coffin. The design team visits regularly to pay its respects and draw inspiration.

Like a lot of fashion companies of its era, Gucci didn’t preserve its full history in real time. It had to be reassembled. All told, there are about 37,000 pieces of Gucci rarities, flotsam and priceless artifacts housed in the archives. They represent the arc of Gucci’s story thus far.

Guccio Gucci was born in 1881 into a Florentine family that manufactured straw hats. He moved to London in search of opportunity and found a menial job at the Savoy Hotel. “He saw the European wealthy class traveling with all of these beautiful suitcases and luggage, and that gave him the idea that when he got back to Florence he could manufacture that for this wealthy European traveling class,” says Sara Forden, author of “House of Gucci: A True Story of Murder, Madness, Glamour, and Greed,” the family history on which the film is based.

The family soon opened a boutique on Rome’s Via Condotti — and, in the aftermath of World War II, American soldiers returned home with Gucci trinkets as souvenirs. The company eventually opened a store in New York City, an expansion led by Guccio’s son Aldo. “He was the marketer in the family,” Forden says. “He realized the Americans wanted this cachet, so he started spinning these stories about how Gucci was a saddler to nobility.” But it was a marketing ploy. “They weren’t connected to nobility at all. They were from humble, hardcore manufacturing roots in Italy,” she says.

The third generation, Maurizio Gucci, tried in vain during the 1980s to heighten the elite image, hoping to shape Gucci into an Italian version of Hermès. But Gucci was already enmeshed in American culture; it was connected to new wealth and the fizzy celebrity economy. It was bonded to the belief that hoi polloi could take charge of their story.

“The Gucci family, it seems to me, they invented the company in a very Italian way,” Michele says. “French brands, they really reflect the monarchy in a way. This company and this family just really expressed the creativity of human beings. … They were really just designing in a very free way. That’s why they started to work for the jet set, for Hollywood stars, because they were less snobbish. They loved American people.” Gucci’s history is wondrously democratic and marvelously nouveau riche. It welcomes the arriviste, and that affection is reciprocated. “America embraced Gucci and Gucci responded,” says Emil Wilbekin, who was editor in chief of Vibe magazine from 1999 to 2003.

Actor Lu Han wears a top reminiscent of one of Michele’s pussy-bow blouses to a Gucci Aria show in June in Shanghai. (VCG/Getty Images)

A Gucci shoulder bag, shown in June, that was inspired by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, a fan of the fashion house. (Edward Berthelot/Getty Images)

LEFT: Actor Lu Han wears a top reminiscent of one of Michele’s pussy-bow blouses to a Gucci Aria show in June in Shanghai. (VCG/Getty Images) RIGHT: A Gucci shoulder bag, shown in June, that was inspired by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, a fan of the fashion house. (Edward Berthelot/Getty Images)

A dress from Gucci from summer 2006. (Maria Valentino for The Washington Post)

A velvet tuxedo, from the brand’s fall 1996 collection by Tom Ford. (Maria Valentino for The Washington Post)

LEFT: A dress from Gucci from summer 2006. (Maria Valentino for The Washington Post) RIGHT: A velvet tuxedo, from the brand’s fall 1996 collection by Tom Ford. (Maria Valentino for The Washington Post)

Over the course of a century, the company has reinvented itself multiple times, arguably more often and more successfully than any other modern luxury house. Balenciaga has had several influential shifts, but it hasn’t been as lucrative. Most brands anywhere close to Gucci’s size have settled into a reliable simmer regardless of who’s at the helm: Chanel, Hermès. Their strength is in their consistency: little boucle jackets and black dresses with camellias; the Birkin.

Gucci angers and shocks and seduces. It has been remade for baby boomers, Gen Xers and millennials. In its early days, Gucci catered to jet-setters and American celebrities such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. It costumed the Studio 54 crowd during the heyday of disco and outfitted the D.C. lobbyists of Gucci Gulch. In 1980, it even had a bit role in “The Official Preppy Handbook,” with its loafers listed as requisite footwear.

At the end of the 20th century, after Gucci went public under Tom Ford, the company’s success made Wall Street swoon for fashion at a time when most design houses were still family-dominated endeavors. Gucci delighted in hip-hop while many luxury brands were squeamish at the thought of all those new Black and Brown customers.

“Gucci is good at tapping into the cultural zeitgeist. Other brands rise above it or look at celebrity as something they have to deal with,” Wilbekin says. “Gucci, especially under Tom Ford, really embraced hip-hop and hip-hop culture. When I’d go to Milan for men’s [fashion shows] I’d have a one-on-one with Tom Ford. He wanted to know what was happening on the street, to understand how the community was reacting to his work and what they were wearing. … The Black community and the Latinx community would embrace what he was doing and remix it.”

Over time, the brand name has entered the lexicon to indicate a specific iteration of cool. To be Gucci is to be all right, in control. It’s to strive and to succeed and to be utterly comfortable showing off that success. In honor of the brand’s centennial, Michele has tried to make an exhaustive count of all the songs that have mentioned Gucci since its founding. His current estimate is 22,000; he notes that “when we’d try to fix the number, another song would come out.” He attributes Gucci’s robust presence in music to the brand’s ability to shape-shift. It’s always telling a story of self-invention. Lineage doesn’t matter. “You don’t think of Gucci as an old brand, blah, blah, blah. When you are thinking about Gucci, you are not thinking you are rich. When you go through all the songs, they’re talking about a cool person.”

Gucci’s history is wondrously democratic and marvelously nouveau riche. “This company and this family just really expressed the creativity of human beings. … They were really just designing in a very free way,” Michele says.

Michele’s friends call him Lallo — but so do the young fans who spot him on the street, where he is sure to stand out. He is 48, of modest height with a boyish build. He wears his dark brown hair below his shoulders, sometimes braiding it into pigtails. He has heavy brows and a full beard speckled with gray.

He tends to wear … everything. Unlike many fashion designers, Michele doesn’t have a streamlined, daily uniform of form-fitting plain T-shirts or ruthlessly tailored black suits. He wears fingers full of signet rings, quirky T-shirts that look as though they’ve been pulled from the twofer bin at a vintage shop, silken dressing robes that could have been borrowed from Jean Harlow’s costume closet, dad jeans, sun hats, elegant blouses and, of course, Gucci loafers. He is not the discreet, behind-the-scenes puppet master of style. He is a memento mori, a David LaChapelle photograph, the Sistine Chapel, a jazz riff, a rap video. He is a Times Square billboard for his version of Gucci: eclectic and egalitarian.

Today, at the archives, Michele wears faded blue jeans, a Gucci “eschatology” jersey, loafers and a treasure chest of vintage diamond jewelry from his personal collection. He greets me with a smile and a hello. At least, I think he’s smiling. His eyes are definitely smiling. We’re both masked because despite vaccination requirements, Gucci is taking every precaution, especially with its creative capital.

Michele opens by talking about Pope Francis and his popularity and how so many more tourists now make a pilgrimage to the Vatican to see this Holiness compared with the previous one, and when they do, they pass through the neighborhood in Rome where Michele lives. His home is just off Piazza Navona, the iconic square dominated by Bernini’s massive Fountain of the Four Rivers.

Michele jokes about how Pope Francis captivates the tourists. The designer speaks in asides. He footnotes his own thoughts. “Francesco is kind of a superstar. He’s a kind of rock star. Yeah, a hippie rock star compared to the others,” Michele tells me. “I mean, I quite like him. I’m not Catholic. I came from a Catholic mom and a kind of, you know, religious dad, but not really Catholic. I love rites and I love all these, you know, sacred things. It’s something that’s really fascinating.” He continues, “Francesco — it’s a new way to be a pope, the way he lives and doesn’t want to live in a super-rich palace like a king. He’s not a king.”

“I always say that the Pope and Queen Elizabeth are the oldest, hugest pieces of power in Europe,” he explains. “The Catholic Church is amazing in terms of marketing. They’re still on the stage after thousands of years.” One can almost imagine the collection that would emerge from this train of thought — one that references the ecclesiastical garb of the church, the bright colors and traditions of the queen and the loose-limbed informality of hippies.

Michele studied at the Academy of Costume & Fashion in Rome, which is where he grew up. His father was a nature-loving musician who worked at the Fiumicino airport as a technician for Alitalia, and his mother was an assistant in a film-production company. Michele was drawn to fashion not by the high-minded inventiveness of Yves Saint Laurent or the technical expertise of Christian Dior, but by the charismatic subversiveness of Gianni Versace — a designer who was also immersed in popular culture.

But it was Michele’s time at Fendi during the late 1990s, he says, that left the most significant imprint. “The environment was very inspiring. I have to say that I was in this amazing little studio in the center of Rome, in this room with this beautiful fireplace, with this beautiful painted ceiling and full of books. It was like the cave of Ali Baba,” he recalls. “It was like a beautiful mess. That is still my way to work.”

About 37,000 pieces make up the Gucci archives, housed in a refurbished 15th-century palazzo that was once the company’s factory.

A chandelier in a conference room at the archives.

LEFT: About 37,000 pieces make up the Gucci archives, housed in a refurbished 15th-century palazzo that was once the company’s factory. RIGHT: A chandelier in a conference room at the archives.

A room at the archives features pieces that have been worn on the red carpet or to other events by celebrities.

Garment bags of clothes at the archives.

LEFT: A room at the archives features pieces that have been worn on the red carpet or to other events by celebrities. RIGHT: Garment bags of clothes at the archives.

Michele is a chatterer and does not believe in cloaking himself in mystery the way some designers do. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that Michele talked his way into this job. He had the talent and the follow-through to back up his words, but his initial conversation with Bizzarri wasn’t a job interview. Bizzarri was hunting for design-room intel, and Michele was a long-timer at Gucci who’d risen through the ranks. Tom Ford hired him, and he’d stayed on to work with Ford’s successor, Frida Giannini. Michele was still there after her rather abrupt departure in January 2015. He’d been steadfast for almost 13 years.

Michele and Bizzarri spoke during that meeting for hours. Visually, they are opposites. Bizzarri’s style is as austere as Michele’s is sumptuous. He’s a tall, lean man with a cleanshaven head who wears heavy-rimmed glasses and who can most often be found in a black or gray suit and white shirt. But in Michele, he found a man overflowing with creativity, one who was itching for something new and who had a personality with which he was simpatico.

Michele’s first Gucci collection was menswear — completed in barely five days. He hadn’t been named creative director yet. He was just Giannini’s deputy who had been given a creative challenge by Bizzarri. The first model down that runway in January 2015 was a flaxen-haired young man in a red pussy-bow blouse with his fingers adorned with rings. Fashion changed in an instant. Still, when Bizzarri named Michele to the top job a few days later, the near unanimous reaction from the fashion industry was, “Who?”

“I was trying to put on the catwalk, you know, how it’s beautiful to be exactly who you want to be. I was trying to go through fashion in a very free way. I was trying to care about personality. About differences,” Michele says about his work. “I was trying to give voice to the most hidden beauty and to the things that I love that I maybe was not, at that time, seeing in fashion.” He continues, “You know, it was like thinking that fashion was losing its soul, its diversity, its ambiguity.”

His nearly seven-year tenure as creative director is something of an eternity in the current fashion system where folks hold that post for three or four years and then move on or are sent packing. “If you want to get the soul of the place where you live, you have to stay and go deep. I’ve been here since 2002, but I am in this position — it’s such a beautiful trip — because I had the opportunity to know very well this place,” Michele says of Gucci. “If you want to interpret it your own way — a brand or a place — you must stay. You can’t run away.” He adds, “It’s like in a relationship. You must love in a very deep way to be in a relationship. You can’t just stay for a while and then leave.”

For our tête-à-tête, Michele had come to Florence from his design studio in Rome, where he works in his version of Fendi’s beautiful mess. There, light filters in through the tall windows of a historic palazzo and illuminates the colorful carpets that form a patchwork on the floor. Upholstered chairs are scattered about, and pottery, statuary and books fill an expansive table. The ceiling is ascribed to an acolyte of Raphael. A large, cream-colored valise — one that recalls the era of steam-powered ships — is embossed with Michele’s initials. The objects, he tells me, are both his inspiration and his obsession. “Honestly, I have to say that it’s pretty beautiful. It’s a gift. I mean, I’m not the kind of person that says, ‘Eh, It’s nice.’ No. It’s something unbelievable,” Michele says. “Everything is an inspiration.”

Before the pandemic, Michele also commuted to Milan several times a year for Gucci’s big catwalk productions. The country’s main fashion hub is there; it’s where retailers come to stock their shelves, and it’s where Bizzarri’s office is located. Gucci looms especially large in Milan because the stolid city is all about business and Gucci is a commercial marvel. Company revenue has nearly bounced back to 2019, pre-pandemic levels, ringing up nearly 4.5 billion euros ($5.2 billion) in sales in the first half of 2021 — much of that in North America, although growth isn’t as strong as it once was.

But Florence is Gucci-ville. A kind of Gucci-land. What was once a Gucci museum — a somewhat staid memorial to seasonal collections — is now Gucci Garden, which is not a wonder of botanical delights but an amusement park of Instagram-worthy sets that are odes to the Gucci fantasy. There’s also a restaurant of significant ambition that is overseen by a Michelin-starred chef and where one can order a 30 euro tortellini in cream sauce that is so perfectly prepared it will make you take the Lord’s name in vain. Gucci’s historical aspirations, its merchandising acumen and its mythology all live here in Florence.

Like every industry, fashion has had to carve out a path forward after the pandemic shutdown. When the lights were out in factories and showrooms, there was a great deal of public posturing about the need to reassess fashion’s connection with its customers, to slow down, to produce less, to build a kinder industry. Most of those optimistic notions quickly withered away. As soon as governments once again allowed fashion shows with live audiences, the invitations went out. Waiters stood ready to keep champagne flutes filled. Editors and retailers began racking up frequent-flier miles. And once again the industry is manufacturing loads and loads of stuff.

“At the beginning, I thought, ‘Oh my god. Finally, I have time to relax.’ Then probably, after one month, I was like, ‘Okay, it’s done. I’m relaxed,’ ” says Bizzarri, 59. “I learned I could slow down a little bit, but at the end, I like what I do.”

Gucci’s new approach to fashion is just different enough that it stands out. In its latest project, called Vault, prime archival pieces are dusted off for online sale — a venture that is mostly an exercise in frustration as Vault objects sell out in about a nanosecond. The company regularly hosts the work of newer designers in shops and online, bringing attention to lesser known and more diverse names.

And prefaced by a lengthy manifesto posted to Instagram soon after the pandemic began, Michele unhitched the company from the tyranny of an exhausting fashion schedule that the entire industry hated even though it was of its own making. Gucci collections are no longer labeled spring or fall. They’re simply given a whimsical name like the newest child in a sprawling family. Michele works on his own schedule.

The spring 2022 shows in New York and Europe wrapped up in early October, but Gucci unveiled its latest addition, Love Parade, this month in Hollywood — specifically on Hollywood Boulevard, with the city as a backdrop and the Walk of Fame as the runway. “I really wanted it to be in the street because everything in my life came from the street. I get inspired from the street,” Michele explains. “People that are really living are working in the street.”

The event celebrated Gucci’s long-standing affection for America and its celebrities, with the company also sponsoring the annual Art + Film Gala at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which this year honors artists Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley, along with filmmaker Steven Spielberg. “I’ve been so inspired by L.A. in these seven years. It’s a place where the rules are completely broken,” Michele says. “When I went to L.A. many years ago, maybe 20 years ago, I thought it was such an unfashionable city. But now I understand what is fashion: Fashion is life.”

“You can go to have a coffee at a very chic place and the people going there, you see crazy colors, crazy outfits — the way they experiment, the way they express themselves. And the other part of L.A. that I love is the old Hollywood, the idea of beauty and the invention of beauty,” he says. “In Europe, in Italy, you have so many rules, the Catholic Church. In L.A., I feel really free. I feel without connections. It’s not a city of monuments. It’s just about dreams. … It’s like we changed the antique Greek and Roman culture of the gods and we started again in Los Angeles with another dream — that is the movie stars.”

Michele’s iteration of Gucci also continues to nurture the relationship with hip-hop culture, such as in a recent collaboration with Gucci Mane, while speaking with intention to the rising political and cultural might of the LGBTQ community. “He tapped into that, and that makes the brand more exciting,” says Wilbekin, who founded Native Son, a media platform for Black gay men. “Men in pussy-bow blouses is hot.” Gucci celebrates the mutability of gender even as some folks wring their hands over who gets to use which bathroom as if the answer were a matter of national security.

Gucci’s goodwill with marginalized groups may well help it navigate heightened cultural demands for greater diversity and inclusivity. In 2017, when Gucci was accused of appropriating the work of Dapper Dan — the designer of bespoke luxury garments to Harlem’s elite and hip-hop’s finest, who had himself appropriated Gucci’s trademarks for his own purposes in the 1980s — the brand forged a partnership with him. When a social media firestorm erupted over a sweater that recalled blackface, Gucci responded with a raft of initiatives aimed at elevating the voices of people of color. Gucci recovered from the sort of racially charged missteps that might have gotten lesser companies permanently tarred and their leadership fired.

“They used it as an opportunity,” Wilbekin says of the controversies. And instead of critics asking if they could ever wear Gucci again, the question was a more forgiving: When? The answer appears to be: Now.

In the luxury fashion ecosystem, Gucci manages to be both a commercial behemoth and a creative juggernaut. It’s a public company that can rattle the nerves. It tugs at the culture with both creative energy and financial might. And at the moment, Gucci is pushing us toward a more welcoming, more open place. One where we get to write our own story — or a least believe that doing so is still possible.

“The capability that you have to reinvent yourself is so big and so huge and so immediate. It’s creating an addiction in a way. So you want to do that every time right. That, to me, is the beauty of being part of this company,” Bizzarri says. “You can have a kind of worldwide impact.”

Robin Givhan is The Washington Post’s senior critic-at-large writing about politics, race and the arts. Previously, she covered the fashion industry as a business, as a cultural institution and as pure pleasure. She will discuss this story with Rhonda K. Garelick, a contributor to the Creators issue, for a Behind the Cover conversation on Nov. 23 at 11 a.m. Register at washpostmaglive.com.