The cost of getting South Africa to stop using coal

Dumisani Mahlangu sits in the cab of a dragline excavator, digging 40-tonne shovels of coal from an opencast mine outside Johannesburg. “Coal has made me what I am,” he says of his well-paid job in a country where one in three people lacks work. “I wanted to be a doctor, but God put me in the mines.”

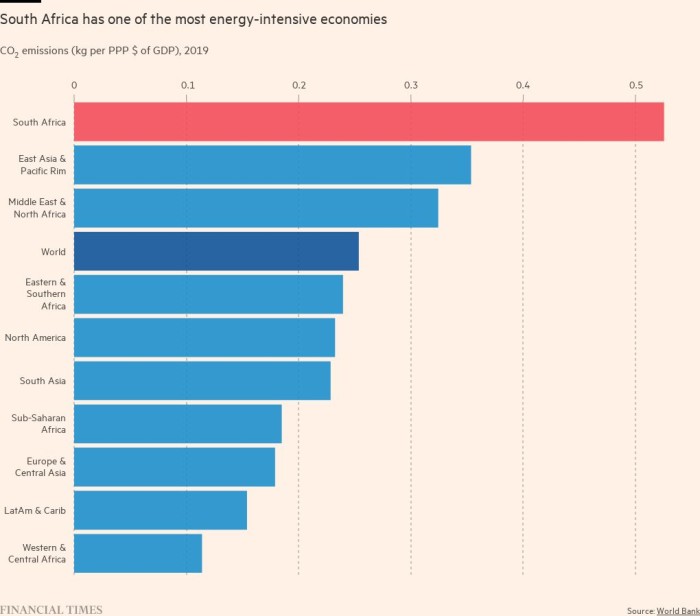

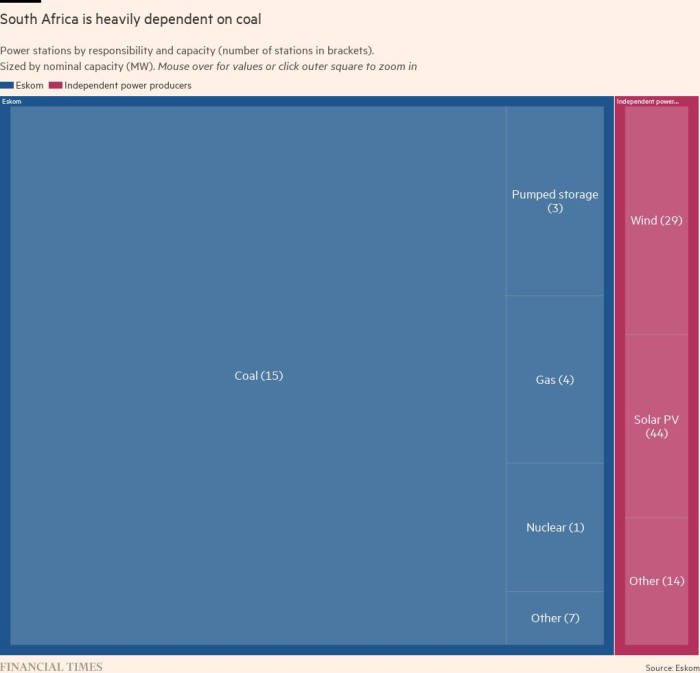

South Africa is among the world’s most coal-dependent nations. Coal accounts for roughly 85 per cent of its electricity, making the country of 60mn people the world’s 13th-biggest emitter of carbon, bigger than Britain.

That puts South Africa, with income per capita of roughly $7,000, among the most inefficient at turning fossil fuels into economic output. But it also means there are quick wins to be had if finance can be found to help South Africa — and other countries like it — transition more quickly to clean energy.

“Mitigating a tonne of carbon in South Africa is a tenth the cost of mitigating a tonne of carbon in Europe,” says André de Ruyter, chief executive of Eskom, South Africa’s coal-hungry state power utility. “So the value proposition for the German [or other rich-country] taxpayer is, because carbon is a global phenomenon, let’s give our money to a country where you get more tonnes of decarbonisation per euro than anywhere else.”

That proposition was taken up a year ago at the COP26 UN climate conference in Glasgow when a group of rich countries — the UK, Germany, France and the US — as well as the EU banded together to pledge $8.5bn to help South Africa shift from coal.

The so-called Just Energy Transition Partnership, or JETP, was presented as a model of north-south co-operation and a template for future partnerships with other heavily coal-dependent countries such as Indonesia, Vietnam and India.

A year on, with COP27 due to start in Egypt on November 6, the contours of the South African partnership are taking shape. Terms of the $8.5bn financing have been hammered out. Meanwhile, South Africa has come up with its own $95bn five-year energy transition plan, in which the $8.5bn is to play a catalytic role by attracting private-sector investment.

“This is the first five years of a multi-decade journey,” says Daniel Mminele, the former head of Absa bank who was recruited by Cyril Ramaphosa to run South Africa’s presidential climate finance task team. As well as slowly replacing coal with renewable energy, the plan envisages green hydrogen and electric-vehicle production.

Yet negotiations between South Africa and western lenders have been fraught. The governing African National Congress is wary of damaging the coal industry, one of the few in the country that is black-majority owned.

“We have to do this right,” says Rudi Dicks, a former trade union leader who now advises Ramaphosa. “In Britain you just closed down the mines and said, ‘Go to hell.’”

South Africa also wants a higher proportion of grant money, wary that loans will merely add to its debt.

“Some countries must be lauded for their readiness to put money on the table, but others regrettably are still in the narrative stage,” says Pravin Gordhan, South Africa’s minister for public enterprises.

Pretoria has also complained that Europe is slowing its energy transition just as it is pressing South Africa to accelerate its own. “Europe, which was the chief protagonist of the hardest line in terms of emissions, is now in trouble. It is keeping its own coal-fired power stations going and importing coal, including from South Africa,” Gordhan says.

Decrepit infrastructure

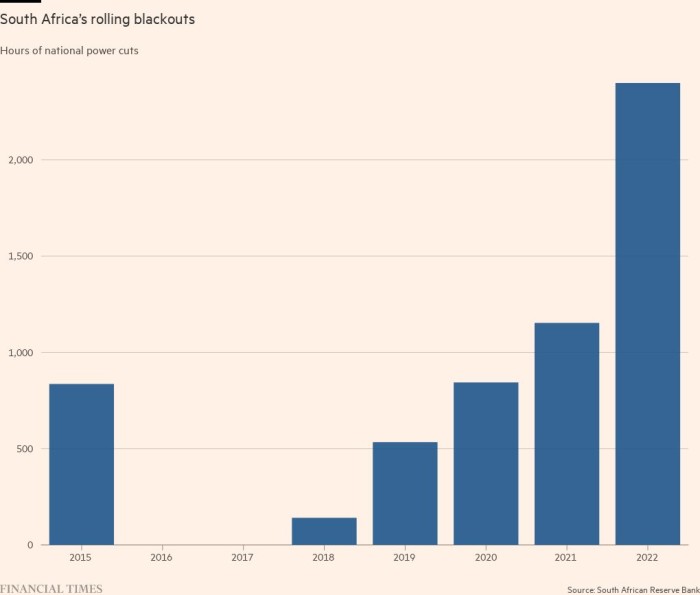

Still, the logic for South Africa to move to renewables is strong. Its decrepit coal-fired power stations, with an average age of 42 years, are juddering to a halt. The electricity system, with peak demand of 38 gigawatts, is operating at 58 per cent capacity — not enough to keep the lights on.

Rolling power cuts of up to five hours a day are crippling industry and making life unbearable. Traffic lights stop, jamming up roads. Abattoirs lose power. When power goes down, criminals steal overhead cable, further wrecking the system.

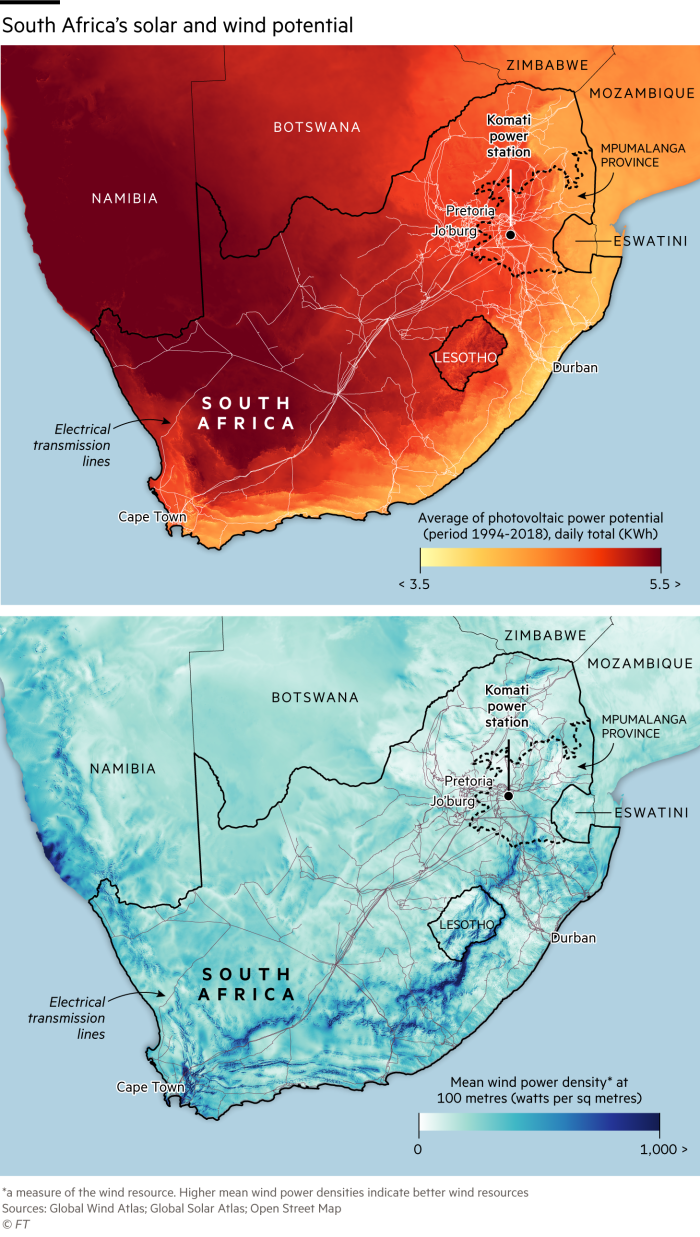

The obvious solution is to add cheap renewable energy as quickly as possible. With an average 2,500 hours of sunshine a year, South Africa is among the world’s top three in solar potential. It is estimated to have enough wind to generate 6,700GW of power, roughly 175 times current needs.

South Africa has first-hand experience of the havoc extreme weather can wreak. In April, more than 250 people died and car plants were inundated with mud and water when 200 millimetres of rain fell on Durban, a coastal city, in a single day.

South Africa is one of 17 megadiverse countries, meaning climate change affects its ecosystems differently. “Northern KwaZulu Natal is going to have cyclones,” says Barbara Creecy, environment minister. “The Western Cape is going to get drier and drier, which is very serious because it is the country’s breadbasket. And the rest of the country is going to get so wet and so hot you won’t be able to grow maize anymore. So how are you going to feed people?”

An added threat is coming down the track. When Europe starts taxing so-called embedded carbon at its borders from 2035, nearly half of South Africa’s mineral and manufactured exports will be at risk.

With these dangers looming, South Africa last year presented the UN with an improved emissions target, promising to cut total greenhouse gases from 550 megatonnes to between 420 Mt and 350 Mt by 2030. The upper end of that range was compatible with limiting global temperature rises to 2C. The lower end was roughly consistent with 1.5C. South Africa was making the world an implicit offer, Creecy says: “To get to the bottom of the range, we would need help.”

The international response was the $8.5bn JETP. “We believe this will accelerate the decommissioning of coal,” says Mafalda Duarte, head of Climate Investment Funds, a multilateral fund that is part of the group. In October, the CIF agreed a $500mn loan for South Africa’s energy transition, as well as $500mn for Indonesia.

Yet in the year since the South African deal was unveiled, at times, each side has claimed, at least in private, that the other is acting in bad faith.

“This is peanuts,” says Crispian Olver, executive director of South Africa’s presidential climate commission, referring to the fact that most of the $8.5bn is concessionary finance and loan guarantees, not grants. “The $8.5bn, even if it was all grant, would not settle the debt,” he says, arguing that the global north, which built its wealth on fossil fuels, must pay for transition in the global south.

South Africa has noted with displeasure that Rishi Sunak, prime minister of Britain, which chairs the JETP group, had stated his intention to skip this year’s COP in Sharm el-Sheikh.

Western lenders say it was made clear from the start that grant money would be limited. One accused South Africa of engaging in “theatre”. Duarte says that, because of long grace periods and very low interest rates, as much as half of CIF loans are effectively a grant. “This is much more cost-effective than South Africa borrowing on the markets,” she says.

Still, suspicion remains. “You’re going full throttle on coal in Europe,” says Tiro Tamenti, general manager of New Vaal colliery, a huge opencast mine that, like much of South Africa’s coal industry, is majority black-owned. “Are you offering pills that you don’t want to swallow yourself?”

In South Africa, mineworkers, truckers, coal companies and the mafia-like syndicates that have infiltrated parts of the industry, oppose a rapid shift to renewables.

Gwede Mantashe, the energy minister and a former coal miner, has described himself as a “coal fundamentalist”, although he has acknowledged South Africa’s need to transition, albeit at its own pace.

Even those who support a quicker adoption of renewables, including Gordhan, insist it must be handled carefully. “This must be a ‘just’ transition where just means workers, just means communities, just means miners,” he says.

International lenders support the “just” concept. But privately some question Pretoria’s ability to take on vested interests in the coal industry and to deliver a plan that is politically sensitive for the ANC, which has strong links to mining unions. “For South Africa,” says one western official involved in the finance negotiations, “it was always a political problem.”

Jobs at risk

Mpumalanga is coal country. The eastern province has more coal mines and more fume-enshrouded coal-fired power stations than the rest of South Africa combined. Poorer and with higher jobless levels even than the national average of 34 per cent, it relies on coal for 100,000 direct jobs, plus thousands more in ancillary industries.

One of Mpumalanga’s oldest power stations is Komati. Commissioned in 1961, at its peak a decade ago, it was generating nearly 1GW of power. Since then its nine units have been gradually decommissioned until only one was coughing out electricity. On Monday, at precisely 12.41pm, that too was switched off.

As the countdown to decommissioning has approached, Komati has been busy with visits from bigwigs and consultants trying to figure out what comes next. “The only person who hasn’t visited is the Queen,” jokes Jurie Pieters, Komati’s acting general manager, who oversaw the shutdown on Monday with what he called mixed emotions.

Mandy Rambharos, who manages Eskom’s just energy transition, says: “We could have put on a padlock and walked away.” Instead, she says, Komati is being used to demonstrate how old power plants can be repurposed and a fair transition realised. By 2035, Eskom plans to shut down nine power stations, most of them in Mpumalanga, terminating 15GW of power and putting up to 55,000 jobs at risk.

Among the stream of visitors to Komati is David Malpass, president of the World Bank, who will come this week bearing a cheque for $497mn to help repurpose the plant. Eskom plans to install 150MW of solar power, with some panels placed directly on the old ash heaps, as well as 150MW of battery storage and 70MW of wind power. It wants to grow plants under some of the solar panels in a technique known as agrivoltaics, though this plan has been stalled by cumbersome local content rules. Still, all 193 employees have been offered alternative Eskom jobs.

Plans are also in train to open a factory on the site to produce micro-grids, mobile solar-power units built on old shipping containers. The idea is to employ 500 full-time workers churning out 900 units a year. “As we decommission these power stations we create new blood,” says Nick Singh, who is leading the project.

Not everyone in the local community is convinced jobs will materialise. “We don’t have information in the public domain,” complains Thomas Mnguni, a community activist in Mpumalanga. “We cannot have a just transition without labour being on board.”

As well as community scepticism, there is another threat: obstruction from within Eskom itself. By the time Komati was shut down this week, neither solar nor wind power had been installed. The person overseeing the repurposing has been suspended, says Rambharos.

Behind the scenes something more sinister may be going on. Eskom was one of the main targets for so-called “state capture”, the systematic ransacking of institutions during the near-decade when Jacob Zuma was president until 2018. One result was that Eskom increased the number of coal supply contracts to small mines, expanding the scope for dodgy deals and criminal activity.

De Ruyter, appointed chief executive in 2020 to sort out the mess, describes how one scam works. Coal bound for power stations is loaded on to trucks that are tracked by GPS. But during the journey from mine to power station, the tracking system is jammed and the truck is diverted or hijacked. Good coal is sold abroad where, since the Ukraine war, it fetches triple the price. Trucks are reloaded with discarded coal, essentially rock, from disused mines and the weight made up with water and scrap. When this detritus is fed into power stations it causes havoc.

“When I joined, a forensic investigator came to me and said, ‘Congratulations, it must be great to be head of South Africa’s biggest organised crime syndicate,’” de Ruyter recalls. “I was quite offended at the time, but looking back I think he might have had a point.”

The future’s in renewables

Assuming Eskom can clean up its act, there are other problems to solve. One is encouraging private power companies to generate renewable energy. In July, faced with worsening power cuts, Ramaphosa doubled the year’s procurement of renewable energy to 5GW.

He also removed limits that, until last year, had — almost inexplicably, given the chronic power shortages — restricted the amount of power private operators could produce. Critics blamed the restrictions on government suspicion of the private sector and the influence of the powerful coal lobby. De Ruyter has a simpler explanation. “It’s difficult to steal sun and wind,” he says.

The next problem is where renewable power should be generated. Northern Cape, where the sun shines brightest, is far from Mpumalanga and poorly served by transmission lines. Wind is much the same story. It will cost billions of dollars to build new transmission lines to take power to the big urban centres.

Eskom is encouraging solar and wind operators to set up in Mpumalanga by auctioning off spare land. The first round was three times oversubscribed and resulted in contracts for 2GW of power.

South Africa hopes to move by 2035 to an energy mix dominated by renewables but with some coal, gas and nuclear to meet peak demand. In time, the mixture will alter further, says Gav Hurford, Eskom’s national control manager. Known as the “King of Darkness” because of his role in scheduling power cuts, Hurford says pump storage technology — essentially giant natural batteries — can solve problems associated with the intermittency of renewable power.

Ebrahim Patel, minister of trade and industry, says that to make the transition complete, South Africa must build an electric vehicle industry — or risk being shut out of European markets. He also wants to export green hydrogen by turning sunshine into liquid, a field where South Africa has proprietary technology. Still, some question the wisdom, or even the feasibility, of exporting hydrogen from energy-starved South Africa to faraway markets in Europe.

Patel is not deterred. Initially, he says, rich countries will need to buy South Africa’s green hydrogen even at uncompetitive prices as part of the international effort to help bankroll its green transition.

His view of how it will be subsidised, at least initially, goes to the heart of the friction between Pretoria and the JETP lenders. Some of these say that South Africa is either grandstanding or has unrealistic expectations of what rich countries will pay for. “Blaming us may be their happy place, but it won’t address the issues,” says one person familiar with the lenders’ position.

For South Africa, by contrast, the $8.5bn on offer is a small downpayment on a much bigger moral obligation. Speaking not only for his country, but for developing nations generally, Patel says: “If we have to carry the burden of transforming our economies on our own, it will essentially be unaffordable.”

Data visualisation by Chris Campbell