The Florida Retirement Community Fighting Physical Decline With High-Tech Treatments

It’s 5:30pm on a Tuesday, and happy hour has begun at Brownwood Paddock Square inside the Villages, a 55-plus retirement community in Florida. Grey-haired couples amble along the pavements, toting folding chairs and coolers. A band is playing “Blue Suede Shoes” in the corral. Maskless throngs in windbreakers and visors shuffle out of the restaurants and bars, scoping out good spots for the concert. Customised golf carts line the curb, glimmering in the light of the setting sun.

In the past, I would have smiled condescendingly at this scene – look at these oldsters, rocking out on their new knees! Instead, I drink it in, pondering my own mortality. I’m 55 – officially old enough to live at the Villages – and I’m here to visit the new Aviv Clinics, which offer a compelling, potentially game-changing therapy to combat the effects of ageing.

The Villages are a location but also a concept: a place where the almost old and the actually old go to feel less old. It’s where you can act young without being young, and it’s where an estimated 132,000 people and counting are testing the hypothesis that youth is more of a mindset than a number. There are 50 golf courses and more than 3,000 clubs and activities, from karate to knitting. It may seem counter-intuitive, but this city/club/social experiment may offer a glimpse of the future. Your future, perhaps.

The Western world’s population is ageing. As a result of medical breakthroughs, more of us are living longer, and the baby boomers born after the Second World War are in their senior years. It is estimated that, by 2030, more than one in five people in both the UK and the US will be aged 65 or over. Naturally, this is changing how we think about growing old, challenging the idea that pensioners should rest and take things easy.

Glenn Colarossi, the head of Aviv’s business development and my host, likens the Villages to a college campus for the retired. “They like to have fun,” he observes. If the Villages are reimagining our notion of the golden years, Aviv is greasing the wheels – and the joints – of this revolution. Its goal, Colarossi tells me, is to increase a person’s “health span”, not just their lifespan.

Pioneered by Israeli physician Dr Shai Efrati, the clinic studies each client down to their DNA and constructs a personalised plan for staying physically and mentally well. Its centrepiece is hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), in which patients breathe pure oxygen at varying pressures in a sealed chamber, potentially inducing cell growth and expanding blood vessels in the brain. The original research centre in Israel opened 15 years ago, and the Florida site opened in March last year. If I were entering the 12-week programme, I’d meet with a physical therapist, a physiologist, a doctor and a dietitian; engage with millions of dollars’ worth of machinery and submit my DNA, which would result in a 200-page book of code and genetic indicators that the experts would parse. There would be 60 sessions in the hyperbaric chamber, as well as before-and-after brain scans. The full programme costs roughly £42,500.

But is this just another get-young-quick fad for the super-rich? Or do HBOT and customised evaluation of your physiology offer some chance to counteract declining brain and body function and help in the fight we all fight – the one against ageing?

Regeneration Game

The Aviv lobby where I check in is a cavernous expanse of white tile and polished wood. It is celestially sleek. If the designers were going for a God’s-waiting-room vibe, they nailed it. I’m scheduled for a sample of the three-day assessment, condensed into two days. I don’t think of myself as old. I run and take boxing classes. The other day, when I barked at my teenage daughter to get off the phone and do the dishes, she muttered, “Grumpy old man.” We locked eyes and laughed. It was funny because it was so not true.

But I do have persistent lower-back pain, and the odds are 50-50 that I’ll have to get up in the middle of the night to go to the toilet. Then there’s the looming shadow of declining

brain function, which for someone who lost his father to Alzheimer’s is too terrifying to joke about.

My first evaluation will determine my physical and cardiopulmonary state. I meet with Ankita Shukla, a trim, sharp woman who runs me through a gauntlet of tests to measure the flexion, extension, rotation and abduction of every joint in my body, zeroing in on the limited range of motion in my neck, back, wrists, hips and (sigh) knees.

In one test, to assess my “dual-task ability”, she asks me to briskly walk to a cone while counting down from 100, subtracting each number by three. I utter only two numbers, one of which is right. She recommends a serious stretching regimen for my body, neck, hips and wrists. For posture, she offers a quick cheat: stand with my back against a wall for more than a minute at intervals throughout the day. To increase my dual tasking, she suggests I count backward – numbers, months, the alphabet – during my workouts.

Shukla hands me off to physiologist Aaron Tribby, a young and fit body movement specialist. Tribby straps me into the Gaitway 3D, a biomechanics treadmill that measures my gait and step pressure to check my coordination and see if I’m losing functionality. I have some foot rotation, which might be caused by tight hip flexors, rigid ankles or taut hamstrings. He gives me exercises to remedy all three.

Next, I visit Dr Roger Miller, Aviv’s charming clinical psychologist. “I’ve got the best job here, because everything is controlled by the brain,” he proclaims with a smile. “I’m going to tell you five words. I want you to repeat them to me.” I find it easy. Then I take a battery of increasingly difficult cognitive tests: the written Montreal Cognitive Assessment (at the end of this, he asks me to recite the five words again; not so easy); the NeuroTrax,to assess functions such as memory, attention and problem-solving; the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB), which looks at processing speed, flexible thinking and spatial memory.

The results: “You showed comparative strengths in your non-verbal memory, fine motor speed and coordination, and executive-function skills.” And in a sentence ripped right from my wife’s playbook: “There were relative weaknesses in your information-processing speed and sustained attention.”

None of the testing so far is particularly cutting edge, and the advice, while sound, is mostly stuff that I already know I should be doing. I then meet with Dr Mohammed Elamir, the lead physician at Aviv who interprets all of the data from the team, including from specialised brain scans that track blood flow in the brain and identify diminished zones, to gain a holistic view of how a patient is ageing. Elamir gives me a basic neuroscience history lesson, which, like everything else at Aviv, traces back to its co-founder Efrati.

He tells me that he was drawn to Aviv because he came across research by Efrati that indicated that central nervous system cells in the brain could regenerate and rejuvenate. “That is not what we were taught in medical school,” he says. “This was not deemed feasible.” Now, he says, thanks to Efrati’s HBOT research, there is preliminary evidence they can.

Efrati is a professor at the Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University and the founder and director of the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Research at Shamir Medical Center. He has been studying the effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for more than 20 years, he tells me on a Zoom call. He’s 50, with close-cropped grey hair and a warm, TED Talk-polished bedside manner. Efrati says that he developed an interest when a stroke patient with an ulcerated leg wound was put in a hyperbaric chamber – an accepted wound therapy. After a series of treatments, he noticed the woman’s neurological disabilities were improving as well. This led him to investigate the regenerative effects of HBOT on the brain. He discovered in 2007 that, indeed, “Neurons and blood vessels in the brain can be regenerated.”

He credits this to a phenomenon called the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox. By manipulating levels of oxygen in the chamber, you can essentially fool the body into perceiving that it’s being starved of oxygen – a state called hypoxia – without harmful side effects. During the hyperoxic stage, oxygen floods the cells. According to Efrati, this can promote the production of stem cells, which are valuable because they can develop into almost any cell in the body. Treatment can also promote the branching of new blood vessels into areas of the brain damaged by events such as strokes.

Rebooting the Brain

Efrati started treating stroke patients with HBOT in 2007, then brain-trauma patients in 2008. Today, he works with people who want to remain physically and mentally active. “About five years ago, we decided to move forward with targeting ageing as a disease,” he says.

His recent research results are intriguing. Notably, a clinical trial of 35 people aged 64 and older last November indicates that HBOT can increase the length of telomeres, which decreases with age. Another of his clinical trials published last July found evidence of cognitive enhancement in adults ages 64 and older after HBOT. The specific benefits were increased cerebral blood flow, resulting in an improvement in executive function, information processing speed and attention.

However, there is scepticism in the wider medical community. Usually, small clinical studies would be followed by larger, multi-centre, randomised clinical trials, says Dr James E Galvin, a professor of neurology and the director of the Comprehensive Center for Brain Health at the University of Miami. This hasn’t happened with HBOT yet. Galvin, who is engaged in dementia prevention and therapy research, is familiar with Efrati’s work. “I think one should be cautious about over-interpreting results from very small studies performed at single sites with very small effects,” he says. “I’m not discounting the research. There’s just not a lot of research on HBOT used on patients with various forms of dementia.” He adds that the majority of studies appear to be on just one type of dementia: vascular. “I’m cautious about rushing treatments for broad commercial use before the research shows that it’s effective.”

Though HBOT therapy is new, I see about 20 other patients during my visit, mostly couples, in their seventies and eighties. I’m reminded of something that Elamir told me: for many patients, the motivation for treatment is the fear of becoming a burden on their partner, should cognitive decline make them less independent. One patient I meet, Dr Elliot Sussman, is the chairman of the health-care provider Villages Health. Sussman, 69, is 45 “dives” (sessions in the hyperbaric chamber) into the programme. Though the initial MRI of his brain was normal, his goal, he says, is to sharpen his cognitive function. The most notable effect for him has been “a significantly increased need for sleep”, an additional hour or more per night. This is good, the doctors told him. It’s a sign that his brain is regenerating, in the same way that babies need sleep for their growing brains. Sussman feels that the investment will pay off.

Playing the Long Game

After a night observing the Villages’ social scene, I’m up early the next morning to meet registered dietitian Kathryn Parker. She has me stand on the Seca Medical Body Composition Analyser and grip the handles. Within minutes, a report is compiled that assesses my water composition (good, at 58%), my visceral adipose tissue (fat around my organs, which is very good, at 1.9 on a scale that goes up to five), and a host of other things, including skeletal muscle mass (at 28.5kg for my 76kg body, it’s OK; she wants it to be between 29 and 38). I’m losing muscle mass as I age, and I’ll need it to keep from falling down when I’m old. She suggests I do more strength training and eat more protein, recommending snacks of yogurt, cheese and whey shakes. It’s refreshingly straightforward nutrition advice.

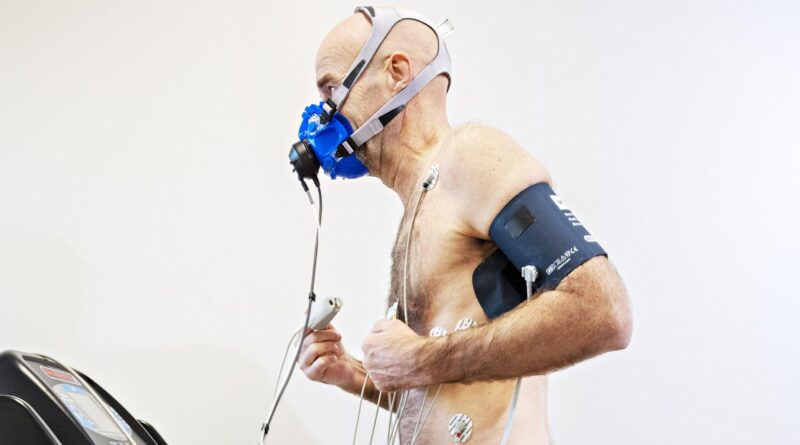

Then I’m back with physiologist Tribby for a spirometry and VO2 max stress test. He tapes on 10 electrodes for the ECG, straps a mask over my head and puts me on a treadmill. As both speed and incline gradually increase, I’m instructed to run until I can’t go any further, whatever that means. Nine minutes later, I find out. The ensuing report shows that my lung efficiency is normal for my age and gender. At 34kg/min, my maximum oxygen intake during intense exercise is a little better than average. But before this goes to my head, Tribby points out that elite athletes test more than double that. My report is five pages of mediocrity, challenging my self-image as fit. To improve, he recommends that I exercise three or four days a week at 70-80% of my maximum heart rate, which is 165bpm. I also need to add sessions of HIIT and an endurance workout.

Finally, I’m ready for my dive. The chamber is designed like an aeroplane’s first-class compartment, to combat the claustrophobia some may feel – and because it looks cool. I wear a mask to breathe the oxygen and sit in a very comfortable chair for an hour (half a regular session). The scheduled air and oxygen intervals at pressure induce the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox. My breaths through the mask are slightly easier than breathing through a scuba regulator, but I’m conscious of every inhale and draw the air deep into my lungs. My one session won’t have a measurable effect on my brain, but I get the idea. When I emerge, I’m light-headed. That night, I sleep deeply, my brain presumably awash in oxygen.

My two days give me only a glimpse inside the Aviv process. The data I get from my biometric measurements puts me in a good place – no immediate evidence that my body is ageing faster than my brain, or vice versa, just that I am getting older. This one-stop check-up has taught me that it’s great to have access to a team of medical experts under one roof, and also that I need to adhere to health and anti-ageing best practices. Physically, I’m inspired to do more stretching, improve my posture, increase my exercise intensity and

eat more protein. I might even take up knitting to stay sharp. My exposure to the Villages has challenged me to look unflinchingly at the future, and both play and prepare for the long game.

More than anything, I’m relieved that there were no cognitive red flags. I couldn’t afford the £40,000-plus price tag to potentially reverse a brain problem. Hopefully the science behind HBOT will be proved effective and the cost will come down. Until then, the prospect that age-related cognitive decline can be staved off gives me optimism that I’ll stay active long enough to keep that smirk off my daughter’s face for decades to come.

You Might Also Like