The best children’s books of 2021 | Children and teenagers

Children’s books bounced back in buoyant style in 2021. As bookshops reopened in the spring, children’s books enjoyed an 11% boost in sales against the equivalent period in 2019, according to the Bookseller. Michael Rosen’s own journey of recovery from Covid was movingly documented in Sticky McStickstick (Walker), illustrated by Tony Ross.

A move towards greater diversity heralded a rich array of new and emerging talent. Hey, You! by Dapo Adeola (Puffin) took an empowering, celebratory look at growing up black, showcasing the work of 18 black illustrators. Amari and the Night Brothers by BB Alston (Farshore) is first in an outstanding fantasy series following a young black girl and her adventures in the Bureau of Supernatural Affairs. Neurodivergent author Elle McNicoll’s debut, A Kind of Spark (Knights Of), winner of the Waterstones and Blue Peter awards, told the story of an autistic girl campaigning for a memorial of witch trials. The Marcus Rashford Book Club was created to give books to children who need them the most; Rashford’s You Are a Champion, written with journalist Carl Anka, is the year’s bestselling children’s nonfiction book.

In September, more than 100 British authors and illustrators signed an open letter urging the UK publishing trade to reduce carbon emissions. The move reflected a trend for children’s books addressing climate change from Hannah Gold’s wonder-filled The Last Bear, illustrated by Levi Pinfold (HarperCollins), to Dara McAnulty’s Wild Child (Macmillan), a glorious journey into nature.

The children’s book world also lost two much-loved creators this year. In May, Eric Carle died. Carle’s innovative approach to texture and colour were ahead of his time, as evidenced by his 1969 debut, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, and much more. Jill Murphy died in August. The Worst Witch was an instant success in 1974, inspiring seven further titles. Her prolific picture book output included the Bear and Large Family series, capturing the warmth and chaos of family life in a style that brought her millions of fans the world over. Fiona Noble

Picture books

In a year that provided plenty to scream and shout about, Barbara Throws a Wobbler (Puffin) felt both fitting and therapeutic. Nadia Shireen’s hilarious tale of a cat having an off-day (sock problems, a dropped ice-cream, you know the sort) charts Barbara’s descent into a huge tantrum, depicted as a raging, raspberry-coloured cloud. The turning point comes when Barbara acknowledges her foul mood – “If I made you, can’t I UN-make you?” – and begins squishing it down until it disappears completely.

With illustrations the colour of bright, shiny jelly beans and a witty text that culminates in a genius guide to bad moods (to help people differentiate, say, “a tizzy” from “a huff”), Shireen’s latest gem ought to come on prescription.

The masterly A Shelter for Sadness (Templar) by Anne Booth also features a tricky set of feelings depicted in scribbly blob form by David Litchfield, but here we witness a boy building a den for these emotions. Booth was inspired by the words of Holocaust victim Etty Hillesum, who wrote: “Give your sorrow all the space and shelter in yourself that is its due…” and the result is a perfectly pitched, heartfelt meditation about living alongside grief.

Plenty of authors memorably celebrated difference this year, including the acclaimed writers and real-life partners Zadie Smith and Nick Laird, whose wonderful Weirdo (Puffin) stars Magenta Fox’s fabulously drawn guinea pig in a judo suit. Martin Stanev’s equally quirky The Planet in a Pickle Jar (Flying Eye) concerns a seemingly boring granny who has secretly been preserving Earth’s wonders in large glass jars for the enjoyment of future generations. Lauren Ace and Jenny Løvlie brought us The Boys (Little Tiger) which, like its award-winning predecessor The Girls, lovingly depicts the bonds between four friends.

Author-illustrator duo Mick Jackson and John Broadley returned with another visual treat after 2020’s acclaimed look at nocturnal life, While You’re Sleeping. We’re Going Places (Pavilion) has us swooping, sailing and skating as it explores the many ways we travel through the world and through our lives, from childhood to old age. Broadley’s exquisite pen-and-ink drawings evoke the work of early 20th-century artist and designer Eric Ravilious but with an energy all of their own (regulars at London restaurant Quo Vadis will recognise Broadley’s style; since 2012 he’s provided the illustrations for its menus).

Other exceptional nonfiction works came in the form of Flora Delargy’s graphic novel-esque Rescuing Titanic (Wide Eyed), a stunning debut about the supposedly unsinkable liner, and David Olusoga’s Black and British: An Illustrated History (Macmillan). Olusoga’s latest, aimed at children aged nine and over, follows bestselling middle-grade and adult versions of his examination of 1,800 years of black British life and it truly sings in picture book form with the history made even more vivid via a trove of old paintings, maps and photographs combined with bold artwork by Melleny Taylor and Jake Alexander.

While not strictly a Christmas book, Richard Jones’s Little Bear (Simon & Schuster) felt really festive with its rich, red cover featuring a white polar bear amid a flurry of tiny golden snowflakes. The palm-size bear found by a boy in his garden is rendered so delicately by Jones that you can almost stroke its soft, fuzzy coat. A warm hug of a hardback, Little Bear is almost guaranteed to get children feeling cosy for Christmas. Should it fail, try giggling away any residual grumpiness with Shireen’s mood-boosting book. That should work whatever the season… Imogen Carter

Chapter books

Whatever the age bracket, plot drives most children’s fiction. Two of 2021’s most original chapter books were actually top-tier thrillers disguised as “children’s literature”. In Elle McNicoll’s Show Us Who You Are (Knights Of), protagonist Cora (on the autism spectrum) navigates the neurotypical world with occasional frustration; her new friend Adrien (who has ADHD) views everything with an eyebrow raised. His father’s firm, the hugely plausible Pomegranate Technologies, creates holograms of deceased loved ones to help bereaved families. They want Cora to assist in getting their AIs just right. Then Adrien goes missing. This gripping second novel from the award-winning McNicoll asks important questions about what is real and how to remain true to oneself.

In Nicola Davies’s career-crowning The Song That Sings Us (Firefly), the Jackie Morris starling on the cover belies the epic battle of mindsets within. An undeclared guerrilla war is raging between city-dwelling technocrats, beset by internal power struggles, and those who resist the extractivist machines. In this globe-spanning tale of high stakes and cross-species comradeship, three siblings come to understand their family history and the energetic field that connects all living beings. In a similar vein, anyone gripped by Piers Torday’s landmark The Last Wild series will find this year’s prequel, The Wild Before (Hachette), essential reading.

Just as important as plot is world-building. In Efua Traoré’s immersive Children of the Quicksands (Chicken House), 12-year-old city girl Simi is sent to stay with the grandmother she barely knows in her village, where traditions remain vivid. Deprived of both wifi and explanations, Simi seeks to solve the mystery of her family rupture. The forest and Yoruba legend loom large in this original, dream-like debut that crackles with as much reality as magical realism.

Forests full of signs also abounded in Amy Raphael’s debut novel, The Forest of Moon and Sword (Orion/Hachette), in which a resourceful young girl, Art, sets out to save her medicine woman mother, accused of witchcraft.

Perhaps this year’s most three-dimensional female protagonist, though, was bored, plucky April, transplanted to a rapidly changing Svalbard by her workaholic scientist father in The Last Bear (HarperCollins). When April encounters an injured polar bear, she cannot ignore his suffering. Author Hannah Gold is careful to keep the bear as wild as possible within the confines of a children’s story and April is quick-witted and possessed of an optimism that frequently nearly backfires; the climate crisis is as much a part of the landscape as Svalbard’s crisp vistas, drawn by the excellent Levi Pinfold.

Pictures remain an eloquent part of the reading experience, even in this age range. Two author-illustrators stood out this year. Tim Tilley’s debut novel, Harklights (Usborne), combined classic storytelling with distinctive, atmospheric graphics. Young orphan Wick labours in a match factory workhouse when he discovers a strange infant creature. But where does all the wood for the matches come from? And what of the forest dwellers whose homes are being destroyed?

Finally, The False Rose (translated by Peter Graves, Pushkin) by Jakob Wegelius had it all: plot, world-building and detailed drawings of 1920s Lisbon and Glasgow, where this sequel proper to 2014’s The Murderer’s Ape is set. Narrated once again by the human-like ship’s engineer, Sally Jones, this engrossing nautical yarn unfolded as sumptuously as its artwork, recounting in flashback the extraordinary events kicked off by the discovery of a mysterious necklace. Kitty Empire

YA books

This year, young adult books have enjoyed a profile not seen since the days of Twilight and The Hunger Games thanks to the BookTok phenomenon – a bookish corner of social media app TikTok, where young people post short videos inspired by the books they love. Bestseller lists were soon full of their recommendations, of largely backlist American titles, including Adam Silvera’s They Both Die at the End (Simon & Schuster), E Lockhart’s We Were Liars (Hot Key) and Kalynn Bayron’s Cinderella Is Dead (Bloomsbury).

In new publishing, fantasy with strong feminist themes dominated. Raging against the patriarchy in spectacular style is Iron Widow (Rock the Boat), in which Xiran Jay Zhao reimagines the life of China’s only female emperor in a fusion of history and sci-fi action. In Lionheart Girl by Yaba Badoe (Zephyr), Sheba is born into a family of powerful West African witches and must escape the shadow of her dangerous mother; a dark and dazzling coming-of-age novel, rich in atmosphere and magic realism. Caroline O’Donoghue made her young adult debut with All Our Hidden Gifts (Walker), offering a fresh take on teenage witches in a contemporary Irish setting, its authentic view of friendships and relationships proving just as beguiling as the tarot readings and emerging powers. Books inspired by mythology further tapped into this trend, Jessie Burton’s Medusa (Bloomsbury) giving Greek mythology’s ultimate antiheroine the chance to answer back. A young girl cursed by the gods and exiled to an isolated island, Medusa’s is a story of self-discovery and survival. Olivia Lomenech Gill’s hypnotic full-colour art makes this one of the year’s most desirable gift books.

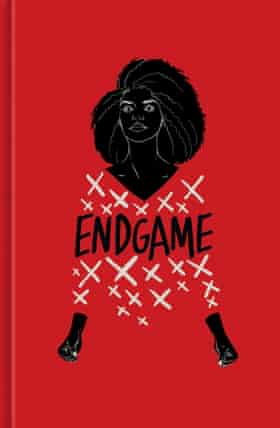

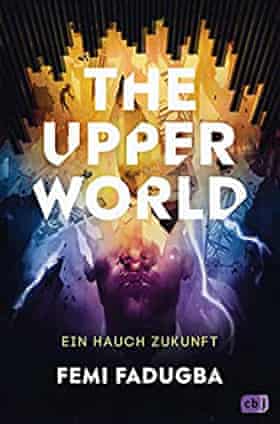

Twenty years after Sephy and Callum’s story began in Noughts and Crosses, one of YA’s most loved series came to an emotional and exhilarating close in Malorie Blackman’s Endgame (Penguin), as compelling and timely as ever. Although very different genres, two of 2021’s most striking British debuts were also driven by themes of race and power. Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé’s smart and moreish high-school thriller Ace of Spades (Usborne) sees the only two black students in an exclusive school team up against an anonymous bully, exposing a sinister campaign of privilege and corruption. The gritty realism of life in Peckham, south London, was spliced with a mind-bending time travel thriller in Femi Fadugba’s cinematic The Upper World (Penguin). Two teenagers race against time itself in an intriguing mix of high-octane action, whip-smart dialogue, physics and philosophy.

Alice Oseman proved she was one of the most relevant and relatable voices in teenage fiction, winning the Bookseller’s YA book prize with Loveless (HarperCollins), the wise and witty story of a girl’s self-discovery at university. In May, Heartstopper Volume 4 (Hodder) followed, the latest in the graphic novel series centred on a young gay couple. A joyful, tender look at first love and relationships with an inclusive cast, it will be adapted for TV by Netflix in 2022.

For an unmissable festive treat, Juno Dawson’s Stay Another Day (Quercus) follows three siblings heading home to Edinburgh, where their perfect middle-class Christmas is soon threatened by some very big family secrets. Riffing on Christmas romcom themes, it’s a delicious family drama with a gritty contemporary edge. FN