Technology and research offers unrivalled picture of Clare’s earliest farmers

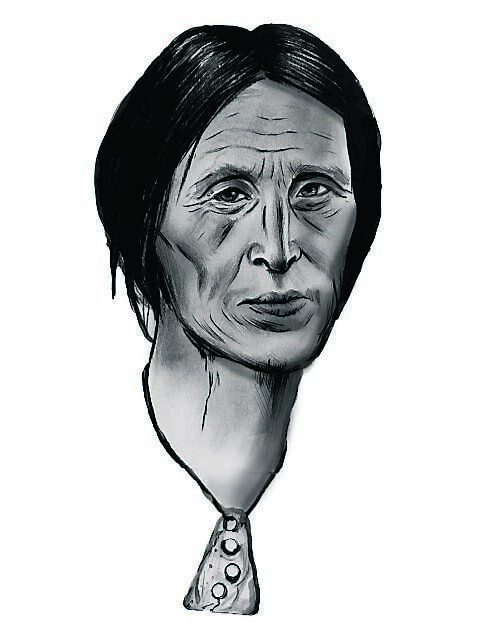

IF SHE were alive today, the Woman of the Burren — let us call her that after the place she was found — would look most like a woman from modern-day Sardinia. Analysis of her DNA tells us that. The same scientific data suggests that she wasn’t very tall, genetically speaking at least, but she was certainly strong and exceptionally healthy.

Her bones confirm that she lived to be at least 55 years old, several decades more than the average woman could expect to survive in the fourth millennium BC.

This robust elder also had a remarkable story to tell because she was among the first wave of farmers who swept into Ireland almost 6,000 years ago. They brought with them agricultural techniques and a tradition of building conspicuous monuments for their dead. Sometime after they arrived in Co Clare, most likely from northern France or Britain, they built a tomb that still looks imposing in the dramatic landscape of the Burren.

Poulnabrone portal tomb, as we have called it, is one of the most photographed archaeological sites in Ireland today — a symbol of an ancient past that is so often embroidered with myth and supposition. Yet, we know what really happened at this singular place. It is now possible to capture a snapshot of Ireland’s earliest farmers going about their daily business, thanks to the enlightening work of archaeologists and genetic researchers.

We can say, for example, that the Woman of the Burren looked nothing like the Irish population alive today.

“If you want an idea of what this person would have been like, look at modern-day Sardinians,” says Dr Lara Cassidy, a genetic researcher at Trinity College Dublin.

“[They] are not completely the same, but genetically they are the most similar alive today.”

We can also say that this woman from the early Neolithic (or New Stone Age) was one of the first farmers who came in a mass migration of people into Ireland almost 6,000 years ago. For decades, opinion was divided on how agriculture got here, but now there is evidence for significant movement into Ireland.

It’s interesting to recall the earliest Irish origin legends that traced the history of Ireland back to a series of “ancient invasions”. The word “invasion” is too blunt, perhaps, as there is evidence that some of the newcomers mixed with those already here, yet there was conflict too, as excavations carried out under Dr Ann Lynch at Poulnabrone have shown.

Analysis of bones, carried out by archaeologists Barra O’Donnabhain and Dr Mara Tesorieri (who herself has Sardinian connections), opened an unrivalled window into life and death in the fourth millennium BC. One of those buried with the Woman of the Burren was struck from behind with such force that the tip of a projectile lodged in his or her hip. It’s not possible to say if the victim was male or female but the weapon, made of chert, penetrated the bone. The person died shortly afterwards, although probably not from this injury.

In any case, a new understanding of those interactions, violent or otherwise, is now emerging thanks to pioneering technology that is coaxing information from ancient DNA in a way that was never thought possible. Dr Cassidy is a member of a team of geneticists from Trinity College Dublin who, with collaboration from Queen’s University Belfast, the National Museum of Ireland and a number of Irish archaeologists, have succeeded in analysing DNA taken from prehistoric bones.

In 2015, for instance, a study of a 5,200-year-old female farmer from Ballynahatty, near Belfast, showed her ancestors came from Anatolia, or modern-day Turkey, a centre of early agriculture and domestication.

It seems, too, that the ancestors of people who arrived in Co Clare around 3800BC also made the same journey. They spread out from Turkey, all over Europe, and eventually settled in northern France. About 6,000 years ago, something happened to make them seek out new ground — a changing climate perhaps, or a growing population. They ventured north by sea, to England, Scandinavia and Ireland. When they arrived, one small group established itself in the Burren.

“It must have been a very dynamic time of colonisation, because that is what it is, with these people coming in who were adept at farming,” says Dr Cassidy. “They were establishing themselves and building these megaliths. One of the big questions I wanted to answer was whether the hunter gatherers already here had any input into these new farming communities, and indeed we are finding some evidence that there was small input from these groups.”

There is evidence of violent interaction at Poulnabrone, though it’s not possible to say whether the newly arrived farmers clashed with other new arrivals, or those already living in the Burren. In any event, they went on to build a structure that was visible and permanent. Standing 1.8 metres high, it was their statement in limestone — their claim on the landscape perhaps, or a concrete expression of the community’s shared identity.

When the Woman of the Burren was born 200 years later, that monument would have been a constant in her life. And, as Dr Cassidy muses, she would have seen an awful lot of ceremonies centred around it in her 55 years: “I wonder if she knew that she would end up there herself?” The remains of only a select few survive. Over a period of six centuries, just 35 individuals (18 adults and 17 children) were interred there — a fraction of the general population. Or at least, only that number survive.

Dr O’Donnabhain and Dr Tesorieri have suggested that this may have been a place of temporary burial and the remains may have been moved on elsewhere. We don’t know how or why they were chosen, but we can at least strike certain criteria off the list. Age or gender didn’t appear to be a factor, as excavations revealed in the mid-1980s. Men and women are equally represented, and there are children too, of all ages.

Indeed, genetic analysis of material from the inner ear bone of one those children revealed that it belonged to a six-month-old boy who had three copies of chromosome 21, or Down syndrome. It is evidence that this early community was caring for a child with special needs 5,500 years ago.

However, blood ties didn’t appear to matter as there is little evidence of genetic kinship between the individuals sampled from this house of the dead. That was one of the more surprising findings from a study of their DNA at Trinity College Dublin.

“There are many possible reasons why a group of genetically unrelated people were placed together in this tomb,” says Dr Cassidy.

“Maybe they were were fictive kinship ties or they were seen as spiritual ancestors or maybe they were chosen because of when they died — on a solstice, for example — or how they died? We can only guess.”

If they were members of some kind of social elite, it was an elite who led physically strenuous lives. There is significant wear and tear to their joints and many of the bones in the tomb bear the marks of degenerative arthritis in the upper spine.

LIKE those buried with her, it’s likely that the Woman of the Burren was accustomed to balancing heavy loads on her head and shoulders. Many of the community had arthritis in their upper limbs too, which was most severe in the wrists and hands. It was more pronounced on the left side, suggesting that many of these early farmers were left handed.

It’s astonishing to think that a detail, such as possible left-handedness, might be evident after five millennia, and so much more can be gleaned from the remains unearthed during conservation excavations led by Dr Ann Lynch in the mid-1980s. The bones of this small farming community were intermingled and disarticulated so it is hard to establish individual stories. Yet, the remains, fragmented and commingled as they were, force open a crack through which we can glimpse the very first farmers and how they lived over 5,000 years ago.

Thanks to the artefacts they left behind, we can also imagine them at their daily work as potters, tool-makers, jewellers, craftworkers. We can say something about how they worshipped, conducted trade and, even at times, did battle. Three adults bear the scars of injuries most likely inflicted in combat.

Life would have been difficult and turbulent. The Woman of the Burren would have seen an awful lot in her 55 years. She lived at a time when sudden, unexpected death was a feature of everyday life. Hunger was common, disease too and broken bones would have been an occupational hazard.

One person had a compression fracture on the foot, probably caused by a heavy weight falling on it. It led to severe arthritis and deformity, yet this person must have been cared for in the community.

OTHERS must have been nursed through their injuries. One young man who suffered a fractured skull lived to tell the tale. He was hit with a blunt object, possibly a stone from a sling, but the wound healed. Another suffered a fractured rib, maybe caused by a blow to the chest, but that injury healed too.

There was, however, one issue that didn’t appear to trouble this community — dental health. The early farmers of the Burren had good teeth, a testament to an abrasive diet low in sugar and high in protein; a paleo diet, Neolithic-style!

Of the 585 adult teeth found in the tomb, just one had tooth decay. Analysis of children’s teeth, where they were found, also showed they were relatively healthy and suffered less physiological stress than medieval children in Ireland.

The rate of tooth loss was low too. The Woman of the Burren may well have had all, or most, of her own teeth when she died. She might, however, have used her teeth as a tool to power-bite or crush various foodstuff or materials. Grooves in some of the teeth also suggest another activity — the regular threading of fibres through the teeth, perhaps to make string or fabric.

That fabric may have been used in clothing or as some kind of bedding in houses that would have probably been more comfortable than the mud cabins of the poorest in the mid-19th century. As archaeologist Barra O’Donnabhain says, Neolithic houses were typically made of timber and rectangular and they would have been equivalent to a comfortable thatched cottage with a central hearth.

We don’t know where the Woman of the Burren lived but she probably lived in a group of houses clustered together. We don’t know what she wore either, but it would wrong to think that her community were in any way primitive or brutish. As Mr O’Donnabhain says: “They were so skilled when it came to making clothes to suit their environment.”

To get an idea, he says, you need only look to the clothing worn by Otzi, the so-called iceman whose remains were preserved in the ice of the Tyrolean Alps for over 5,000 years. He lived about two centuries after the Woman of the Burren but his clothes give an insight into what early Irish farmers might have been wearing.

Otzi’s coat, leggings, loincloth, hat and shoes were all so well-preserved that it was possible to see that they were made solely from leather, hide, and braided grass. They were stitched together with fibres, animal sinews, and tree bast (fibre made from bark), and even repaired several times. There were loops on the end of his leggings that fastened to his shoes. The shoes themselves were made of several layers and were stuffed with dry grass for insulation. Experiments with reconstructed shoes showed that they were warm and comfortable, even over long distances.

Otzi also had a well-equipped tool kit, complete with copper axe, longbow arrows and quiver, flint dagger, retoucher to sharpen tools, along with material to start a fire and two pieces of birch fungus which were thought to have been kept for their antibiotic properties.

Like some of the people in Poulnabrone tomb, Otzi was also the victim of an attack. He suffered a severe head injury but it was the arrow wound to his shoulder that caused his death.

No traces of clothing survive in the Burren, but several pieces of what we might call jewellery do. A finely crafted bone or antler pendant, for instance. It was made by a specialised craftsperson who used flint or quartz tools. He or she was working to a well-thought-out design. The incised outlines show us that.

Did the Woman of the Burren wear it? Did the polished beads, also found in tomb, belong to her too? What of the honed antler toggles; did they once fasten a garment she wore?

The 26 stone tools that also survive give us a glimpse into daily life. They were made from local material and were used to whittle and shave wood and plants (rushes or reeds), perhaps to make baskets, ropes or thatch.

A study of the pattern of wear shows that those tools were not often used to scrap hides or cut meat. These early farmers did not eat much meat, even if they did keep cows, pigs and sheep or goats.

“Only pigs were native to Ireland,” says Mr O’Donnabhain.

“The rest had to be introduced by the earliest generations of farmers by whatever flimsy boats they had. So, in those first years of agriculture, animals like cattle and sheep would have been new and probably a bit wonder-inducing for the local Mesolithic [8000BC to about 4000BC] population.”

The animal remains that survive were of young animals and their bones don’t show any sign of butchering. It seems the community in the Burren ate little meat, though they did drink animal milk. They supplemented that with wholegrains, fruits such as berries and crab apples, nuts and maybe vegetables. There is little sign of animal protein in their bone collagen and, surprisingly, these early farmers did not make use of the sea and its bounty of fish, seabirds, and shellfish at nearby Ballyvaughan Bay. Theirs was a wholly terrestrial diet.

Yet, they did trade with people overseas. A polished stone axe and a fragment of another were made of dacite, a volcanic rock that is not local. Was it a gift used to forge relationships between two distant communities? as archaeologist Gabriel Cooney suggested about similar objects from the period.

It certainly seems to have been a treasured object as great effort was taken to polish it. Two quartz crystals, also found in the tomb, seem to be imbued with a deeper significance which we will never know.

The Woman of the Burren would have known their meaning and much more besides. Her advanced age meant she would have been a keeper of stories, a guardian of community history. As Mr O’Donnabhain explains, most traditional societies value age and in a society where child mortality was very high and parents typically didn’t live beyond their 30s, the wider community and its elders assumed a great importance.

“It really did take a village to raise a child,” he says.

They depended on the wider community to survive so the community becomes much more important and, within that, the elder is a very important person, one who is central to knowledge and skills.

“As an elder, she [the Woman of the Burren] would have been a source of knowledge that was highly regarded. She would have known the social and cultural environment, known where the best foraging grounds were and she would have remembered the lore and history of the past.”

Dr Cassidy suggests that her knowledge of the past probably extended to how her ancestors came from France or Britain and established themselves for the first time in Ireland.

She also probably told stories about the building of the tomb itself, a feat that demanded skill, organisation and considerable collective effort to quarry and transport the stone, possibly using timber rollers and ropes, to the site.

THE archaeologists who excavated it evocatively described what that process might have been like: “The positioning of the large slab-like capstone must have been a nerve-racking but exciting operation, especially as the dramatic profile began to take shape. A ramp, presumably of stone and clay, must have been constructed against the back of the chamber to allow the capstone to be manoeuvred into place.”

The Woman of the Burren, however, would have been able to explain why they chose this particular spot in a landscape that was then heavily wooded with pine, oak and elm and hazel. There were only pockets of exposed limestone here and there, when the first settlers cleared scrub by setting fires.

They picked a place along a routeway into the Burren and one that was near water. Perhaps that was just a practical consideration but portal tombs, with their covered chambers and enormous capstones, are often found near water. As the Poulnabrone excavation report explains: “water tends to be an intrinsic part of most spiritual beliefs. The fact that this particular source is a spring where the water bubbles from the ground and creates a pond when the water table is high might suggest a symbolic association with birth.”

The tomb’s entrance is also aligned with the entrance to a ravine which leads to an amphitheatre-like space that is now covered in hazel scrub. We can’t say how, or if, these people used this natural enclosure as a public space but its existence opens up an intriguing possibility of a community gathering to entertain, perform, maybe pray.

When they went to bury their dead, it was a very complex process that involved extensive manipulation of skeletal remains. Bones were first left to decompose, but not outside. Some bones were burned or deliberately broken and then moved in and out of the tomb.

Some body parts (feet and skulls) seem to have been lined up along the edges of the burial chamber while other bones were jammed into crevices. The fragment of bone — a mandible (or lower jawbone) — that tells us the Woman of the Burren lived to such a great age, was found in such a crevice.

The funerary rituals were deeply significant to the people carrying them out, says Dr O’Donnabhain. There is evidence of the dead being treated in a very similar way at a Neolithic burial site in a cave in Annagh, Co Limerick. “The bones may have been considered treasured ancestral ‘relics’ to be passed among the community. Maybe they were moving between tombs. Is that how they forged alliances?” he wonders.

Others have suggested that such complex burials were a way of emphasising the solidarity of the group at times of social change.

And it was a time of immense social change. As Dr Cassidy says, Europe was shaped by two major episodes in prehistory — the advent of agriculture and, later, the introduction of metalworking. Both innovations brought profound cultural change and genetic change, which is now starting to be charted.

“Now we have this immense power to look at how populations are related to one another. We have Irish genomes from all time periods from the Mesolithic [8000BC to 4000BC] to modern times. With that data, we propose to plot a demographic scaffold for the island,” she says.

Genetic research at Trinity College has identified three distinct Irish populations and two mass migrations. The earliest people, the hunter-gatherer or Mesolithic population, were very similar to Cheddar Man, the famous human male fossil found in England whose DNA revealed that he had blue eyes, dark hair and dark skin.

RESEARCHERS at Trinity College Dublin and the National Museum of Ireland, found similar results in Ireland. Professor of population genetics at Trinity College Dublin, Dan Bradley, said the team had analysed two people from about 6,000 years ago whose ancestors came here at the end of the last Ice Age.

“There is nobody like them alive today,” Dr Cassidy says.

The first migration was the early farmers who swelled the country’s population tenfold to 100,000 people.

About 1,500 years after that, the second wave — and the foundation for the modern Irish population — arrived in the Copper and Early Bronze Age. A huge influx of people moved into Europe from the Steppe above the Black Sea in Russia, bringing with them the oxen and a society that appears to have been hierarchical, male-driven and violent.

They also brought the so-called Celtic curse, haemochromatosis. One of the Early Bronze Age men studied by Trinity College Dublin and Queen’s University Belfast was a carrier for the iron overload disorder that is particularly prevalent in Ireland. Over time, there were other movements into Ireland. The Vikings made their mark as did the Anglo-Normans, but nothing on the same scale as the influxes that took place in the Stone Age and early Bronze Age. The Woman of the Burren was not one of the first farmers to come to Ireland but she probably knew the stories, or possibly earliest legends, about those who did.

Extracted from Through Her Eyes by Clodagh Finn, Gill Books