Michael Rees: how a private equity chief turned the tables on his Wall Street peers

Until Michael Rees became a billionaire this year, he was arguably the most popular man on Wall Street.

Like other successful financiers, Rees works in private equity, an industry with $3tn in unspent capital and a seemingly insatiable appetite for buying houses and hospitals, theme parks and prison payphone systems, genealogy websites and just about anything else that generates cash.

But unlike most of his peers, Rees makes money by buying pieces of the financial industry itself. He has won the trust of dozens of executives, who sold him shares in the closely held investment firms that underpin their personal wealth and have become the most powerful institutions on Wall Street.

In little more than a decade the firm that Rees co-owned, Dyal Capital, has paid out well over $10bn to buy minority stakes in some of the best-performing companies in finance. He has forked out hundreds of millions of dollars to the founders of private equity firms including Silver Lake and Providence Equity; to hedge fund managers including Jana Capital; and to firms such as Golub Capital and Owl Rock, which are displacing banks as chief lenders to a swath of corporate America.

“Rees realised, long before anyone else”, says Egon Durban of Silver Lake, the technology investment group that Dyal took a stake in five years ago, “that alternative [investment] firms with their resilient cash flows would be particularly attractive for investors in a low interest rate world”.

This year Rees, 46, became a billionaire in his own right. Having started Dyal in 2011 as an experimental division on the fringes of asset manager Neuberger Berman, he broke free of his parent company and pulled off a $12bn transaction that amounts to one of the biggest ever stock market debuts by a US private capital group. The enlarged company, known as Blue Owl, instantly achieved a market capitalisation close to that of Carlyle Group, Ares Management and other more established rivals.

The deal created an all-purpose firm that not only gives top financiers a way to convert their paper fortunes into cash and potentially lower their tax bills, but also provides billions of dollars of debt to finance their buyouts. Yet it has embroiled Rees in a messy falling-out with some of the people he helped make rich.

So raw are the emotions surrounding the deal that few are willing to talk about it on the record. But in private conversations, financiers gave contrasting accounts of a transaction that depending on which contested allegations you believe either involved broken promises and purloined secrets, or an opportunistic hold-up in which Dyal’s enemies sought to extract a heavy price.

Two private credit funds — in which Dyal owns stakes — claimed to be so disturbed by the prospect of having to compete with Rees for business while also sending him their internal information that they sued to stop the deal.

The acrimonious dispute highlights the tangled relationships governing the US financial system — and calls into question whether Rees, who won acceptance into the top echelon of finance, has soured his friendships on Wall Street with his bid to create a financial powerhouse of his own.

“It turns out that $1bn is a boatload of money for Neuberger and its partners,” says a senior executive at a financial firm that counts Dyal as a major shareholder, referring to the cash that the asset management firm received as a consequence of the Blue Owl deal. In the executive’s view: “[they have] engage[d] in a transaction that’s bad for . . . clients and bad for the prospects of the Dyal business, all to enrich themselves.”

Making friends in private equity

To prosper as an investment banker is to hitch your own ambition to that of someone far more powerful. Rees, a Pennsylvania native who studied engineering at the University of Pittsburgh and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, arrived at Lehman Brothers in 2001. He would go on to work for the scion of a venerable New England clan that, with the inauguration of President George Herbert Walker Bush in 1989, had become an American dynasty.

By the time George Walker joined Lehman in 2006, the then president’s cousin had already attained a certain stature, having led Goldman Sachs’ alternative investing division.

But running Lehman’s asset management division was a tricky assignment for Walker. The bank’s chief executive Dick Fuld preached growth through acquisition, and had already bought Neuberger Berman, for 70 years the portfolio manager of choice for old-money New Yorkers. The acquisition drive sat uneasily with Walker, who knew that financial groups were expensive to buy and feared a hit to Lehman’s earnings per share.

Anticipating the profound changes in finance that would accelerate in the wake of the financial crisis, Rees and Walker found a way to deliver the profitable dealmaking his bosses wanted. The key was to ignore old-line investment banks and wealth managers, and target a new type of institution that was ascendant on Wall Street.

Hedge fund managers and private equity executives rank among the richest people in America. Their $3tn war chest of investment capital not yet spent comes not from the stock market or individual savers, but from pension funds, foreign governments and other large institutions, which typically pay fees of 2 per cent a year. Originally intended to cover office rent and other basic expenses, those fees have become a source of huge profits, reliably delivering tens of millions of dollars a year to the manager of a multibillion-dollar fund.

When bets go well, fund managers typically keep 20 per cent of the spoils. Wall Street’s share of the profits on a successful fund can run into billions of dollars over a decade. Yet, although the senior financiers who own hedge fund managers and private equity firms are often fantastically wealthy on paper, they are not always flush with cash.

Walker and Rees devised a scheme that used Lehman’s balance sheet to give some of Wall Street’s top earners an early payday, while at the same time helping quench Fuld’s thirst for deals. In short order, Lehman bought stakes in a handful of successful firms, including emerging markets specialist Spinnaker Capital and DE Shaw, the quantitative fund where Amazon’s Jeff Bezos started his career.

The collapse of Lehman in September 2008 interrupted the Rees plan — but not for long. After helping Walker and his team at Neuberger deliver the asset manager from the wreckage of Lehman in 2009, he was rewarded with a senior job at the newly independent firm’s private equity unit. There, he recruited one of the firm’s top lawyers, Sean Ward. Rees and Ward no longer had the backing of an investment bank, so they set up their own private equity fund to raise outside money from institutional investors and buy stakes in private capital firms.

The plan was to amass a portfolio of stakes in private equity firms and, in return, receive fees of their own. Rees, whose young children were called Dylan and Alexia, gave the new firm a portmanteau of their names.

Dyal Capital was not an immediate success. The firm paid so much for the stakes it bought in hedge funds that its first fund lost $0.04 on every dollar. But a round of money raising from deep-pocketed investors in 2014 gave Dyal enough capital to pivot to buying pieces of private equity firms. A chunk of the cash came from the Koch brothers, the Republican party backers and industrialists, according to several people familiar with the situation.

Among the biggest winners of the scheme were a select group of Wall Street executives. Some needed cash, either to fund expansion plans or to pay for their lavish lifestyles. Others were attracted by the idea of replacing a stream of income with a one-off — and lightly taxed — capital gain.

Dyal investors prospered, too, as a tide of money churned through private equity funds. Vista Equity Partners, a tech buyout firm that sold a stake to Dyal in 2015, raised a record-breaking $16bn fund four years later, opening a spigot of fees and making it by some measures Dyal’s most successful investment. The Silver Lake investment surpassed that record earlier this year. Dyal’s two most recent funds have enjoyed strong results with its latest one hitting an annualised return of over 60 per cent, according to the company.

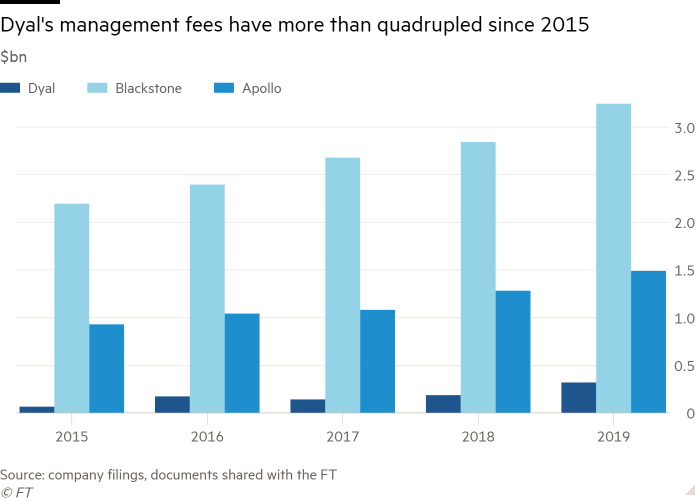

By late last year Neuberger and the Dyal founders, who had made themselves rich and popular on Wall Street by paying top dollar for slices of other people’s empires, wanted to sell a slice of their own. Annual fee income had quadrupled in just four years to $320m in 2019, according to documents reviewed by the Financial Times. The results had exceeded Walker’s wildest expectations, equalling the success of the private equity managers that Dyal sought to back.

But Dyal could hardly buy a piece of itself. So Rees and Ward came up with another plan — one that would put them in conflict with some close allies.

Act of ‘betrayal’

When Alan Waxman and William Easterly sold a tenth of Sixth Street Partners to Dyal in 2017, the veteran credit market investors thought they had struck a gilded friendship.

It was a golden era for Sixth Street and other private credit firms, which were taking over from America’s weakened banks as primary lenders to a swath of heartland businesses. With investors flocking to their funds, several lending firms sold stakes to Dyal. Among them were Sixth Street and its rivals Golub Capital and Owl Rock.

Waxman and Easterly viewed it as more than a business transaction, according to people familiar with their thinking. Rees and his wife began parking their money in Sixth Street funds. Ward and Easterly crossed paths at the New York City private school where they both sent their children. The men sometimes socialised. When Kevin Durant’s Golden State Warriors triumphed over LeBron James’s Cleveland Cavaliers at the 2017 NBA finals in Oakland, Rees and Waxman watched together from courtside seats.

Yet this year they became adversaries. At a Delaware court hearing in March, Sixth Street’s lawyers asked a judge to block the Blue Owl merger, arguing that Dyal was violating its contract. Lawyers for Dyal, which had invested around $400m in Sixth Street only four years earlier, derided it as “a vulture lending firm” that was trying to “extract value that it didn’t earn”. Sixth Street’s assets had roughly tripled to over $50bn since the initial 2017 investment.

At the heart of the court battles was a dispute over an intricate three-way merger involving Dyal and two private lending firms that had previously received money from its funds.

One of the companies, Owl Rock, combined with Dyal to create a firm managing $52bn in assets. The new entity would not only buy stakes in private equity groups, it would also provide the debt for their buyouts. The other, HPS Investment Partners, was the founder of a special purpose acquisition company that had raised $275m on the stock market as an empty corporate shell. That Spac now merged with the enlarged group to create Blue Owl.

Even some executives close to the deal acknowledge it appears rife with conflict.

A Dyal fund had previously invested $500m in Owl Rock, before it merged with Dyal. It meant that Rees and Ward were now managing a fund that is also one of the biggest shareholders in their own firm. While the investors in Dyal’s funds are still waiting for an opportunity to cash out, the stock market listing has already given Rees and Ward big payouts of their own.

The sharpest objections came from executives at Sixth Street and Golub Capital, who were unhappy that Dyal — one of their biggest shareholders — was merging with Owl Rock, one of their most formidable rivals. They characterised the transaction as a “betrayal” that would put their confidential financial information in the hands of a competitor. And insisted that their deal with Dyal gave them a power of veto.

Sixth Street suggested defusing the row by allowing it to buy back the 11 per cent stake it had originally sold to Dyal — at a deeply discounted price. “They offer[ed] to buy back their interest, our funds’ interest in their firm, in an entirely uneconomic value,” Ward, the Dyal executive, testified. “I’m sure they knew it was laughable.” He scoffed at Sixth Street’s claim to be worried about its confidential information, arguing that the updates that Dyal receives from its investee companies contain nothing that is truly sensitive. “[Sixth Street’s] Easterly told me to my face he didn’t care about the information,” Ward said in testimony. However, Easterly in his own court testimony, said that he did consider Owl Rock “a competitor”.

Dyal opted to fight the case. Walker, whose firm Neuberger took out $1.1bn in cash while keeping a multibillion-dollar stake in Blue Owl, was stung by the rancour of the litigation, according to a person familiar with his thinking. Still, he believed the deal was fair.

Ultimately, both courts sided with Dyal. When Blue Owl began trading on the New York Stock Exchange in late May, Rees celebrated a triumph unlike any in his career after facing down threats from some of the toughest characters in finance.

Just weeks later, Rees entered a new stratum of asset owners, signing his firm’s first deal to buy part of a sports franchise in July. The National Basketball Association has been reluctant to allow financial firms to own stakes in teams, but it gave preapproval for Dyal to complete such deals last year. Several financiers who own NBA teams were instrumental in introducing Dyal, according to a person familiar with the discussions.

Dyal’s acquisition of a minority stake in the Phoenix Suns valued it at nearly $1.6bn, about four times the amount Robert Sarver, the owner of an Arizona bank, paid for the team in 2004. On the night the deal was announced, the Suns played and beat the Milwaukee Bucks, itself a team owned by private equity billionaires. The Bucks, however, had the last laugh defeating the Suns on Tuesday night to win the NBA championship.

The ascent of Rees has both bewildered and impressed some of his contemporaries. One of them marvels that the man he first encountered as a mid-level financier only a decade ago now has a billion-dollar fortune and a seat with the biggest names in finance — routinely going head-to-head, he says, with some of “the smartest, toughest, nastiest, greediest sons-of-bitches that have walked the earth”.