Harold Hamm: ‘Republican, Democrat . . . I’m an oilocrat’

Harold Hamm, billionaire oil tycoon and erstwhile Donald Trump confidant, stands in a crisp suit at the head of a long dark table in a boardroom high up an Oklahoma City skyscraper. Maps, leaflets, ring binders and papers are strewn the length of the table. With sudden alarm, I note they include articles on US energy from the Financial Times.

“Mr Hamm is ready for you — very ready,” his head of communications had told me in the downstairs lobby a few minutes earlier. She wasn’t wrong.

Hamm is America’s most famous oilman: a pioneer of the shale revolution of the past 20 years that made the US the world’s biggest oil and gas producer, lessening its dependence on Middle Eastern energy and upending geopolitical norms in the process. To legions of fossil-fuel advocates on America’s right, Hamm, 76, is the self-made hero of the country’s energy renaissance. But with a president in the Oval Office who has promised to “transition” from oil, Hamm is now in a battle to defend this legacy — and I’ve driven eight hours from west Texas to Oklahoma City to ask him about it.

I had imagined the answers would unfold over plates heaped with barbecued pork, grits, fried okra and other staples of Oklahoma cuisine, maybe in the wood-panelled Petroleum Club, a stone’s throw from Hamm’s office.

Hamm has other plans. A well-built man with a weathered face and sometimes halting speech, he doesn’t give off the kind of groomed corporate air emanating from some American executives. Hamm is not into frills. We will eat in the boardroom: a hamburger for him, a chicken club salad for me. Chilled Diet Cokes sit nearby. The papers on the table will be deployed as exhibits as Hamm makes his argument. No rye in sight. The billionaire is living up to his reputation for frugality.

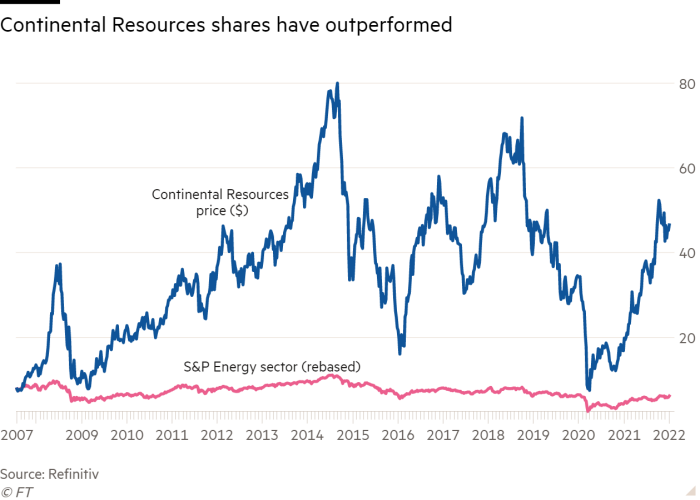

Shares in Continental Resources are collectively worth $18.3bn, as of market close Thursday. Hamm owns more than 80 per cent of them. It’s quite the life change for a man born as the 13th child of a sharecropper in Lexington, Oklahoma, just after the second world war. “It’s something that you fall into gradually,” he says of his colossal wealth. “No one knew until we went public” — the listing was in 2007 — “and then it was a big splash, ‘Oh he’s a billionaire.’ Well, no, I’d been a billionaire for quite a while before that.”

As a rags-to-riches story it has a bit more to it than the overnight success of an internet start-up. And it has also brought him influence. Trump considered making Hamm his energy secretary and the two spoke frequently, especially when the epic oil crash of 2020 threatened the US shale industry that Hamm helped build. The relationship seems to have soured.

“Loyalty’s a big thing with us — it’s very necessary with leaders,” Hamm says. “And I wish Trump could have been a lot more loyal to his people.” To whom was he disloyal? “Everyone around him that worked hard.”

Hamm may no longer be a Trump fan but he is no admirer of the current president either. The first point he wants to make is about Biden and his vote, as a senator in the late 1970s, for legislation that made coal, the filthiest fossil fuel, a cornerstone of American energy security. The US exported the idea, including to China.

These politicians knew of coal’s environmental impact “and still decided to go ahead”, Hamm says, flourishing as evidence some congressional literature he has marked in highlighter pen. “What happened there set the world on a course of destruction.”

Charleston’s Bricktown

224 Johnny Bench Drive, Oklahoma City 73104 (delivered to Continental Resources headquarters)

Cheeseburger $14

Chicken club salad $16

Caesar salad $8

Total (incl tax) $41.28

What should be done? “Put some teeth in” global climate agreements, so coal plants can be closed, Hamm suggests. From a man who once told a Senate committee that he didn’t “believe the science of global warming was proven or settled”, it is a surprising comment. Greta Thunberg would not disagree.

But Hamm is, of course, no green advocate. He wants coal replaced with natural gas, which emits less CO2 than coal when it is burnt but still contributes to climate change. It was soaring shale gas output that pushed down American emissions in recent years, Hamm notes, by displacing coal in power generation. “We’re finally getting down here where it was in the 1970s,” he says, referring to the energy industry’s CO2 pollution. He pushes another paper across the table, bearing a line graph to prove it.

This brings Hamm to his next thesis. Another paper appears, with the letters EQ and IQ written in large print. The emotional quotient is governing energy policy these days, he says, when what is needed is the intelligence quotient. “If we don’t do something real quick, and realise we got to turn around this emotional deal . . . stop the crap and get off the emotional quotient, then we’re close to making some huge mistakes,” Hamm says.

A waiter in a suit appears from an anteroom and briskly lays cutlery at the end of the table not covered with documents.

Hamm barely pauses. Among the errors, he says, is Biden’s energy strategy favouring renewables, such as wind and solar power, and promoting electric vehicles — “virtue cars”, in Hamm’s phrase. Hindering America’s mighty oil sector will only end with punishingly high petrol and natural gas prices, and a renewed dependence on Saudi Arabia, Russia and other autocracies, he says.

It is a familiar line from an American oil sector that has had a mixed few years. Even as shale pioneers like Hamm cracked how to bust oil and gas from brittle rocks in the past decade, sending US output sharply higher, investors were fleeing a sector that never really turned a profit.

Then came 2020’s pandemic-induced crash. By April that year, American oil prices had plummeted below zero for the first time. Bankruptcies tore through the sector, and tens of thousands of people were sacked. Shale companies clung on — but now Biden is killing off America’s precious strategic industry, just as it gets back on its feet, Hamm suggests. “We have an administration in place that really . . . they want to do away with fossil fuels,” he says.

Hamm intends that as a criticism, I reflect, but many Democrat voters would consider it a hopeful mission statement to tackle a climate crisis.

It is also surely more complex. Biden was part of the Obama administration that oversaw a surge in US crude production. Hamm himself successfully lobbied the Obama White House to allow US crude exports. And since Biden entered the Oval Office, oil prices have soared and the shale sector has become consistently profitable for the first time. Production is rising. Continental’s market worth has more than doubled. Isn’t Hamm just repeating Republican talking points?

“Republican, Democrat . . . I’m an oilocrat,” he says. “And also I’m a patriot.” Biden’s policies will simply be bad for American interests, he claims.

And what about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and other progressive Democrats? They seek help for poor communities living next to polluting fossil-fuel infrastructure, clean-energy jobs to sustain the economic recovery and an end to costly oil and gas subsidies. Their vision for America is starkly different from Hamm’s — but AOC is surely also a patriot, right?

“I haven’t met her, and I don’t know how deep she believes in our country,” Hamm says. He would be “glad to talk to her about it”.

Maybe sensing my scepticism, an assistant disappears and returns with a personal letter Hamm sent in 2019 to Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts senator and oil-industry critic, inviting her to visit. Trump had mocked Warren as “Pocahontas”, a reference to her claim of indigenous ancestry. But the tone of Hamm’s letter was gentlemanly and courteous. “We never heard back, of course,” Hamm says. “That’s what you get.”

The waiter returns and silently places our food in front of us. Hamm is diabetic and the Covid-19 mortality rate is higher for those with the condition — a fact that may explain his choice of a modest lunch in the Continental boardroom.

But Hamm is not a typical American corporate titan with an Ivy League background or MBA. His geological knowledge was self-taught. He learnt to fly so that he could more easily explore forlorn parts of the American west, making trips up to North Dakota — home of the first big shale discoveries he made — in his own single-prop plane.

“There was just so much more you could do with an airplane,” he says, his voice dropping a little and a glint appearing in the eyes. “You can’t travel much, north-south, particularly in the Rockies. Everything goes east-west in America, not north-south. So if you wanted to do business in the Rockies, you better own an airplane.”

Some in the oil business who know him say Hamm is touchy about his image. Many Americans know him as the male half of one of the most expensive divorces in history. In 2015, Hamm wrote his ex-wife a cheque for $975m, with the whole tale recounted avidly in the US press.

Hamm is not exactly voluble on the topic. It was the “cheque that went around the world”, is all he says of the money. “You don’t run from it. You just fess up. I am who I am.”

And the notion that a man born in rural poverty helped unleash the American shale revolution is, for Hamm, the defining arc of his biography — more important to him than his divorce or the calls with the White House. “Imagine, it took people like myself to pioneer horizontal drilling,” he says. Not ExxonMobil or Chevron, which initially ignored the shale developments on their own doorstep. “It came from the little people.”

Yet it also depended on Wall Street, which, once risk-takers like Hamm had proved it could work, agreed to finance the shale revolution. Now many of these same financiers are, much to Hamm’s annoyance, scrutinising shale companies such as Continental for their environmental, social and governance performance.

“Capitalism is great. It works — everybody jumps on the bandwagon and makes a buck,” Hamm says, referring to Wall Street’s ESG trend. “But you look at the green stuff, it’s like an industry on its own.”

He doubts it can last. Some of the big asset managers that have tried to use their financial clout to force change, including BlackRock, own stakes in Continental — “and we’re proud that they do”, says Hamm. “But Larry Fink . . . he’s not going to run away from his money.” BlackRock’s boss “knows” that fossil fuels will be around for a long time, Hamm says, because renewables like wind and solar are too intermittent to be relied on. The grid failure in Texas during the February 2021 winter storm, in which more than 200 people died, was proof, he says — although several studies have attributed the crisis to a failure not of renewables, but of the state’s natural gas supply.

Climate change has “almost become a religion”, believes Hamm. “People tend to go to cults once in a while, but when they wake up, they wake up all of a sudden and realise that you’re being led down a path,” he says.

The oil industry’s climate denialism has faded in the face of tightening policy, shareholder activism and social pressure. Some of the biggest US oil companies now talk of curbing their CO2 emissions in line with the Paris climate agreement. BP, a huge oil producer, even pledges to reduce its total fossil-fuel output over the coming years and pivot to clean energy.

Hamm is dismissive. Since BP announced its net zero emissions strategy, the UK supermajor has “underperformed all their peers”, he says. “We see those things happen from time to time, that basically companies cut their throat.”

A pool of ranch dressing is all that is left of my club chicken salad. Hamm has eaten half his burger.

I ask about Trump. Hamm has been a heavy funder of Republicans and deregulation-minded election candidates, especially in fossil-fuel states. But he was none too impressed with Trump’s refusal to concede defeat after 2020’s election. “I don’t agree with a lot of the things he did,” Hamm says. “My advice to him was certainly not to ever question voting and go down that route.”

Should Trump run again in 2024? “I don’t think he should,” Hamm says.

The waiter reappears, clearing the plates. Almost three hours have passed. Hamm now offers to show me his rock collection and we retreat to his private office. A window looks on to a taller, shinier skyscraper belonging to Devon Energy, a shale rival that previously occupied the Continental building.

I count five different guns mounted in the office. A framed letter from Trump and the cover from a gushing 2014 Forbes magazine piece about Hamm hang on a wall. And then the rocks: chunks of shale, arranged as a lepidopterist might display some prize butterflies. Hamm’s eyes shine when he talks about each rock’s provenance. He sounds wistful. “I’ve never been in it for the money — isn’t it crazy?”

Hamm and I speak several times by phone after our lunch. On one occasion it is to talk about the new Hamm Institute for American Energy, founded with a $50m donation (half from him, half from Continental). He insists the centre, which sits atop its own wells, will also study renewables and climate — not just promote fossil fuels. The institute will trumpet the cause of “IQ versus EQ”, he reassures me.

Other calls come after Biden does something that piques the oilman’s fury — such as when the White House asks Russia and Saudi Arabia, not US shale producers, to increase oil production to cool petrol prices, which rose steeply through the autumn.

“It’s the silliest thing you ever heard of,” Hamm says, his Oklahoma drawl unmistakable down the line. He had requested a meeting with John Kerry, Biden’s international climate tsar, but had had no response.

Persuading a climate-concerned world to drop a growing policy shift against fossil fuels just as the effects of global warming become so visible seems a tall order. But Hamm, a man who risked his name — and made his fortune — defying the naysayers to bust hydrocarbons from brittle North Dakota rocks, is up for the fight.

Derek Brower is the FT’s US energy editor

Data visualisation by Keith Fray

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first