FT economists’ survey: people to feel worse-off as inflation and tax rises bite in 2022

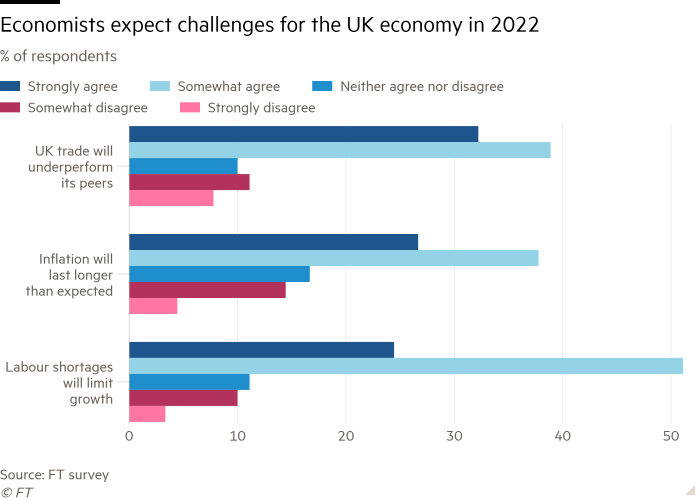

Economists expect UK living standards to deteriorate in 2022 as inflation and rising taxes hit poorer households, while supply-chain blockages and Brexit-related trade underperformance will limit economic growth.

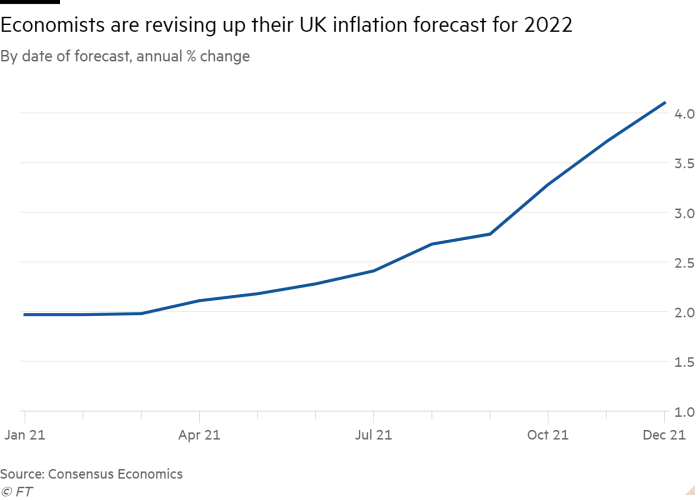

The Financial Times’s annual survey of nearly 100 economists revealed that most expect inflation to outpace wages, while Covid-19 will continue to disrupt production and consumption. At the same time, high energy costs and the increase in National Insurance contributions will hit those on lower incomes hardest.

A majority of respondents also said that the UK’s recovery would lag behind that of comparable economies, with many of them blaming this underperformance on political instability and a lack of any credible long-term economic strategy.

Although many countries are experiencing high inflation, supply-chain disruptions and labour shortages, Brexit would make these problems more severe in the UK, economists said, potentially prompting the Bank of England to raise interest rates more rapidly than other central banks.

Some did see grounds for optimism, noting in particular that the pandemic had sparked a new wave of investment in technology and digitalisation, which could strengthen next year, because of generous tax support. However, several respondents said the benefits could flow into corporate profits rather than into higher wages.

Many also doubted that those gains would be accompanied by the policies necessary to boost productivity in the longer term, such as investment in skills, training and pro-investment regulation.

Here are the full responses to questions about the economic outlook for 2022.

Will the UK economy outpace or lag behind other developed economies in 2022 and why?

Melanie Baker, senior economist at Royal London Asset Management: UK growth is likely to lag the US, partly given a different outlook for fiscal policy if President Biden’s Build Back Better bill passes. Labour shortages seem likely to hold back growth in both economies though. Omicron looks set to weigh significantly on the UK economy into Q1, though Omicron will likely become an issue for more economies in the coming weeks given its apparent high transmissibility.

Kate Barker, trustee at British Coal pension scheme: May outpace EU (faster recovery from Omicron impact) but lag the US due to the US fiscal stimulus.

Nicholas Barr, professor of Public Economics, LSE: More likely to lag behind. My surmise is that the UK will be in the middle of the pack in terms of response to the pandemic, but with the added handicap of Brexit, which is mainly a UK affliction, albeit with knock-on consequences for the remaining EU member states.

Ray Barrell, professor of Economics and Finance, Brunel University London: The negative structural effects of Brexit are still working through the UK economy, and this is the main reason why UK growth will lag behind other advanced economies in 2022. The OBR suggest that over the medium term the self-harm inflicted by the exit from the EU will reduce productivity by 4 per cent, and we may expect this to reduce growth by around 0.5 per cent in 2022. The UK workforce is likely to grow less rapidly than in the past because inward migration will be much lower. Many of the southern and eastern European migrants are likely to move to the advanced economies of north and west Europe rather than the UK. Northern and western European growth will be enhanced by migration diversion, the UK growth disadvantaged, perhaps by 0.2 per cent. Poor design of policies toward Covid-19 will not help raise UK growth, nor will the relatively low rates of vaccination in the UK as compared to northern and western European countries, but the effects are hard to quantify.

Martin Beck, chief economic adviser, EY ITEM Club: The UK should outpace at least the average of developed economies in 2022. While the scope for catch-up growth has diminished, that UK GDP still has more lost ground to make up relative to the pre-Covid-19 position than many of its peers should help. And while headwinds to growth in the short-term aren’t lacking, that the financial position of households is as strong as its ever been, combined with a healthy jobs market, should fuel the traditional appetite of UK consumers to spend. That the UK appears to be taking a more ‘learn to live with’ approach to Covid-19 than other countries should also mean a more cautious attitude towards economically destructive social distancing measures or lockdowns.

David Bell, professor of Economics, University of Stirling: It will continue to lag other developed economies due to a combination of the more adverse effect that the pandemic has had on UK economic activity and Brexit-induced trade frictions.

Philip Booth, professor of Economics, Vinson Centre, University of Buckingham: It will more or less keep pace. There is nothing about UK economic policy that marks it out from other countries in terms of its ability to increase productivity.

Nick Bosanquet, professor of Health Policy Imperial College: Strong performance 2020-1 as a result of government support, vaccine programme and ready adaptation by the economy to Covid-19 conditions. The special factors will not apply going forward. The UK will be around the average. Plus factor that the UK small business/service economy working well: minus is that supply delays/trade shifts as a result of Brexit will be negative.

Erik Britton, managing director, Fathom Consulting: The UK will probably lag behind the US and broadly keep pace with the EU. The US is unlikely to impose any further nationwide restrictions as a result of Covid-19, while that might happen in the UK and EU. And the damage to the level of GDP in the UK wrought by Brexit has largely already been done, so we’ll keep pace with the EU from a slightly lower level

Jagjit Chadha, director, NIESR: The UK economy does not look well placed to lead the advanced country pack in 2022. A combination of a ragged edge over Brexit and political uncertainty will continue to hamper what might otherwise have been a stronger recovery. Specifically trade, investment and FDI will are unlikely to recover strongly and the skills gap in the labour market simply cannot easily be addressed very easily in the coming year alone.

Victoria Clarke, UK chief economist, Banco Santander: After a year in which the UK performed more strongly than its G7 peers, we expect the UK to put in a middling performance in 2022. In the UK’s favour will be the strong starting point for the labour market, including solid recent increases in employment, and further gains ahead. But we expect high UK inflation over the first half of 2022 and only a slow moderation thereafter, crimping household spending power and consumption as the year begins. The Omicron variant reminds us that Covid-19is likely to be with us for a while longer, but UK activity should be impacted relatively less than some of its peers, amid the government’s ‘living with Covid-19’ strategy.

David Cobham, professor of economics, Heriot-Watt University: Poor Covid-19 management (late decision-making, lack of support for business and workers) plus Brexit suggest the UK will lag.

Brian Coulton, chief economist, Fitch Ratings: In growth terms, the UK will outperform a bit but this largely reflects the lagging GDP recovery to date. UK GDP will only recover its pre-pandemic Q4 2019 level by Q2 2022, 6 months later than the eurozone and a year after the US. This leaves more scope for catching up in 2022.

Diane Coyle, Bennett professor of Public Policy, University of Cambridge: Old problems — low investment, low levels of private R&D, inadequate infrastructure, the dysfunctional housing market, policy instability — and new problems — Brexit headwinds, political uncertainty, loss of skilled migrant labour — mean the UK will lag other comparable economies.

Bronwyn Curtis, non executive director, UK Office of Budget Responsibility: It will lag the US, but do a bit better than the eurozone. Japan will lag the rest of the developed economies. The current macro environment is extraordinarily stimulative in the US. The fiscal outlays alone are comparable as a percentage of GDP to the outlays for WW2. Added to that is the fact that the real fed funds rate in Q3 21 was -4 per cent. And there has been QE as well. Household balance sheets and company capex will both be stronger than the UK. The US looks set to withdraw the stimulus more slowly than the UK.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist, Capital Economics: Don’t be fooled by the UK’s GDP growth figures, which will make it look as though the UK is soaring ahead (our GDP forecasts for the UK for 2022 and 2023 are 4.8 per cent and 3.5 per cent compared to 3.0 per cent and 2.0 per cent for the US and 3.5 per cent and 1.5 per cent for the eurozone). The UK’s decent growth figures are mostly a statistical mirage generated by the pandemic.

In terms of the level of GDP, the UK will continue to lag behind the US and the eurozone for most of 2022 for three reasons. First, the UK is having a bad experience with Omicron, which will suppress activity by more. Second, its product and job shortages seem to be having a bigger drag on activity than elsewhere. Third, the hikes in taxes in April 2022 will be another drag.

That said, once the worst of Omicron and the shortages pass, the UK’s GDP will probably start catching up with GDP in the US and the eurozone. So the UK’s behind, but it’s not down and out.

Richard Davies, director, Economics Observatory: We may see some short-term outperformance, due to strong vaccine take up. With Omicron fast on the rise, H1 of the year looks likely to be held back by lockdowns. The UK’s vaccination drive (including boosters) is better than most advanced-country peers and so in the terms of Covid-19-shock type effects, we should outperform.

Longer-run I expect the UK to be a mid-tier performer (compared to G7 and OECD peers) because this is what our long-term productivity performance justifies. The UK has had a turbulent 10-15 years and the sooner we move from emergencies of one type or another — finance, Brexit, Covid-19 — and back to traditional concerns — industrial strategy, productivity — as the primary focus of our economic debate the better.

Howard Davies, chair, NatWest: The Brexit drag effect will be felt, so the UK is likely to grow less rapidly than the US and the core of the eurozone.

Melissa Davis, director, Economics Observatory: Consensus growth expectations for the UK versus the rest of Europe are a little high, so the economy is set up to fail in that sense. The combination of a sharp fiscal tightening, Brexit hangovers and squeezed real incomes suggest growth will undershoot expectations of 4-5 per cent and come in more at 2-2.5 per cent, but this could still be better than the eurozone and around in-line with the US. Indeed, it is not all doom and gloom. If inflation decelerates sharply as we expect and Omicron is a mild and swift route to higher levels of herd immunity, the Services sector could bounce back nicely from the Spring, while Manufacturing will benefit from easing supply-chain pressures and restocking.

Paul De Grauwe, professor, London School of Economics: I believe the UK economy will lag behind other developed economies in 2022 mainly as a result of the collateral damage that Brexit will continue to impose on the UK economy. Recoveries are driven by optimism about the future. That optimism drives investment. Brexit will impose chronic pessimism about the future of the UK economy.

Panicos Demetriades, emeritus professor of economics & former governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, University of Leicester: Although the economy is now recovering from the pandemic, there is still considerable uncertainty whether the bounce back will continue unabated or whether new restrictions will be required to contain the spread of the Omicron variant.

However, by itself, the Omicron variant cannot cause any major disparities with other developed economies. What will hold back the UK relative to other developed countries is the real cost of Brexit in the form of increased border costs, labour shortages and their impact on output and trade.

There is also the possibility that the UK’s monetary policy may need to become tighter earlier than in other developed countries, as inflation pressures are likely to be more pronounced in the UK due to the impact of Brexit on labour shortages, trade costs and, more broadly, the supply chain. and we are already seeing early evidence on that with the Bank of England being the first central bank to raise rates.

In 2021, the pandemic helped to disguise and compound the impact of Brexit on trade and labour shortages, however, assuming that Omicron’s impact is shortlived, the adverse effects of Brexit will become clearer.

As the effects of Brexit become clearer more questions will be raised about the current Tory government’s policies, in addition to current corruption scandals and Boris’ arbitrary, if not chaotic, style of government.

It is quite likely that in 2022, the UK will enter a new period of political instability, with Tory leadership challenges, parliamentary elections and Lib Dems reopening the debate on Brexit.

Political instability could add to the uncertainty already faced by the private sector, hampering new investment and productivity as the private sector exercises the option of “wait and see”.

Wouter Den Haan, professor, London School of Economics: The UK economy will lag behind because its supply chain problems and difficulties in filling vacancies will be larger.

Swati Dhingra, Associate professor, London School of Economics: UK’s got the added impact of Brexit over and above the global trends. So lag behind.

Charles Dumas, UK team, TS Lombard: The UK economy likely will outpace economies elsewhere in the developed economies space in 2022. Admittedly, Omicron presents a threat, with high frequency data suggesting in-person services are already under pressure. Granted, double-jab vaccinations rates are at the lower end of the European scale, but it’s not a wide range (double-jab rates are well above the US), and the UK booster campaign is racing ahead.

Beyond the Covid-19 scare, the Bank of England is normalising because the recovery continues, albeit very unevenly. The main threat to growth globally is that the unwinding of the Covid-19-induced consumer durables boom will swamp the recovery of the underlying cycle. In short, Covid-19 generated a “Zoom Boom”, as people and businesses spent to furnish a world that didn’t exist before. That job is now broadly done, and replacement demand will be modest for some time. The UK, with its services economy, is among the least exposed developed economies to this growth scare. Similarly, the UK is less exposed to the sharp slowdown under way in China, at least in the real economy.

At the same time, the UK went down faster in the Covid-19 recession, so the rebound to the new normal is more vigorous.

Finally, the stimulus overhang in the UK remains one of the largest in the world, at least providing some cushion as monetary and fiscal policy normalise.

Wohlmann Evan, vice-president — senior credit officer, Sovereign Risk Group Moody’s Investors Service: The UK economy will be among the last of the developed economies to recover its pre-pandemic output given the still-significant impact of the pandemic on the UK’s services reliant economy, particularly if the new Omicron variant necessitates further restrictions, as well as headwinds to private investment and exports from ongoing Brexit-related uncertainty. While most supply-side disruptions are expected to be temporary, these supply bottlenecks have been compounded by labour shortages, reflecting both the pandemic and tighter immigration rules since Brexit, with the relationship between supply disruptions, labour shortages and Brexit particularly evident in those sectors such as hospitality and transport. High inflation, high energy bills and planned tax rises will erode household purchasing power, weighing on private consumption.

Noble Francis, Economics director, CPA: It’s difficult to say at this stage. Whether the UK economy outpaces other developed economies will be highly dependent on two key factors. Firstly, it will depend on the extent to which different countries enact social distancing restrictions again in response to current and future Covid-19 variants plus the fiscal stimulus respective governments do in response to sustain, particularly, person-to-person interaction services such as hospitality. Secondly, growth prospects for developed countries will depend heavily on the extent to which high inflation during the next few months affects consumer and business confidence and, consequently, consumer spending and business investment.

Former senior official: We should be catching up after suffering a bigger hit last year than most economies but the continuing problems with trade and labour supply are likely to hold us back even if fiscal policy continues to be relaxed.

Andrew Goodwin, chief UK economist, Oxford Economics: Omicron looks set to make Q1 2022 very challenging. But over the year as a whole we think the UK will outpace most of its peers, simply because it has more lost ground to make up. Sectors heavily reliant on social consumption were reporting output well below ‘normal’ levels even prior to Omicron.

Andrew Hilton, director, centre for the study of financial innovation: Who writes these questions? What happens if it is just ‘in the pack’ — which is more likely?

Dawn Holland, Fellow, NIESR: Weak productivity growth, exacerbated by the impacts of Brexit, will see the UK economy continuing to lag behind other developed economies in 2022.

Paul Hollingsworth, chief European economist, BNP Paribas: Although its annual real GDP growth is likely to be higher than other developed economies in 2022, this reflects a lower starting point for the level of GDP as opposed to a genuine outperformance.

Ethan Ilzetzki, Associate professor in Economics, London School of Economics: UK GDP growth will slightly over-perform other developed economies in 2022 because its shortfall relative to the pre-crisis trend is larger at year-end 2021. Once GDP recovers to its pre-Covid-19 trend, I expect less remarkable growth as the realities post-Brexit Britain and stagnant population growth return to the fore.

Dave Innes, Head of Economics Joseph Rowntree Foundation: As with 2021, the virus will be the main decider of economic growth. New variants are a common shock across developed economies but can have a different scale of impact. The UK currently looks particularly vulnerable to Omicron which could mean it’s again starting the year with the lost ground to make up. I expect the government will again provide fiscal support during periods where the virus depresses demand and that will help restore growth afterwards.

Beyond the impacts of new variants, I expect the UK economy to continue to grow at a similar pace to the eurozone, but not make up lost ground from the start of the pandemic.

Dhaval Joshi, chief Strategist, BCA Research: The UK economy will lag its peers in 2022.

The UK economy fell furthest in the first wave of the pandemic, with GDP collapsing by 22 per cent, compared with 12 per cent in Germany, 10 per cent in the US, and 8 per cent in Japan. So, unsurprisingly, in the subsequent rebound, the UK has bounced the strongest.

But now that the post-pandemic rebound is mostly complete, the ongoing headwind from Brexit will become the main differentiator of UK growth versus other developed economies.

As such, I expect the UK economy to lag its peers in 2022.

Deanne Julius, distinguished fellow, Chatham House: The UK will lag growth in the US but be higher than that in the EU. Momentum is strong partly because excess savings (as a share of GDP) are higher in the UK than in most EU countries. Business investment is also likely to be strong due to the accelerated tax write-off while the EU package is slow to get off the ground.

Saleheen Jumana, chief economist and Head of Sustainability, CRU Group: The UK annual GDP growth rate is forecast to outpace its G7 peers in 2022. While this is good news it may not be celebration-worthy. Why? Because the higher UK growth rate is going to reflect the larger contraction of the UK economy during Covid-19, followed by a more sluggish recovery.

We forecast the UK to be one of the last economies to regain its pre-pandemic size. By the end of 2022, we do expect the UK to surpass its pre-pandemic size, but the gain is going to be smaller than other developed economies.

Lena Komileva, chief economist, (g+) economics: The UK economy was worst hit by the pandemic among major economies, with the greatest shortfall of economic activity relative to pre-pandemic levels, as well as a higher inflation shock; the effects of a weaker starting point and higher price moves will be a stronger “catch-up” percentage change in UK nominal GDP in 2022 in the international comparison.

Barret Kupelian, senior economist, PwC: The outlook for most advanced economies seems to be highly uncertain. So, it is difficult to make any predictions with any degree of accuracy. Having said that, there are three reasons that make me worry about the short-term outlook of the UK economy:

First, the looming combination of tax rises coming through at the beginning of the second quarter of next year — namely the NIC hike as well as the freezing of the income tax thresholds.

Second, high inflation, which is likely to persist, given the expected increases in the energy price ceilings that is due to be refreshed in April.

Third, the uncertainty around the latest wave Omicron. Even though we are not fully clear about the epidemiological outlook, personal responsibility has seemingly translated into effective lockdowns of some sectors of the UK economy. The more muddled government messaging remains, the more likely it is that some sectors of the economy will remain in the “deep freeze”. What seems to be more certain though is that we’re likely to start January 2022 shortages in some sectors of the economy due to the rapid rise in the cases of people with Covid-19 who will need to care for others or self-isolate.

All three of the factors I mention above mean that it is consumer spending that will be hit the most which is the biggest driver of growth in the economy. Britain’s competitors, particularly those in the EU, have less to worry about tax rises. In fact, the next-generation EU investment programme, coupled with the suspension of the fiscal rules for 2022 means that the fiscal authorities in the EU and Eurozone will continue to maintain an accommodative fiscal stance which should help and support growth.

Finally, the Brexit question mark still remains for the UK. On the first day of 2022, full customs controls, which were postponed a few times in the past, will be enforced. We still don’t know how rigorous the implementation of these rules will be but they will nonetheless be an additional burden to doing business.

Ruth Lea, Economic Adviser, Arbuthnot Banking Group: It could well be that the UK grows quicker than other developed economies in 2022, but, this is more likely to reflect the unusually large “measured” drop in GDP in 2020 and the need to “catch up”. Otherwise, I expect growth to be fairly unspectacular all around.

John Llewellyn, Partner, Llewellyn Consulting: It will lag. In addition to the current headwinds faced by all economies, it has also those coming from Brexit. One manifestation will be exports being weaker than they would have been otherwise. More importantly, the inflation impact will oblige the Bank to be more restrictive than other major central banks.

Gerard Lyons, chief economic strategist, Netweatlh: My forecasts echo the message from the IMF and OECD, namely that UK economic growth will exceed that of the US and eurozone in 2022. Despite this, I would not use the term outpace, as I expect the UK to experience a similar growth profile to other developed economies in 2022.

Steve Machin, professor of Economics and director, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics: Lag behind, because it faces the same global trends, but has additional factors restricting growth including the continued effects of Brexit.

Christopher Martin, professor, University of Bath: I think it will lag behind. The UK has performed worse than most other large economies since the pandemic began. I can’t see anything that will change this; consumer expenditure is restrained, investment has been weak since the 2016 referendum, government expenditure is subject to political constraints, and Brexit is impacting the current account.

David Meenagh, Reader, Cardiff University: I expect the UK to grow a bit more than other developed economies in 2022. I expect public spending to fall to pre-Covid-19 levels, which should mean fiscal policy can support the economy.

Costas Milas, professor of Finance, University of Liverpool: Under the assumption that the rollout of the (booster) vaccine programme takes off again, I am pretty confident that the UK economy will outpace most other developed economies. Needless to say, this is very short-sighted because the virus will catch up with us again if the vaccine rollout in the rest of the world lags significantly.

Patrick Minford, professor of Economics, Cardiff University: I am looking for growth of 8 per cent year on year with UK recovery to trend, more than most developed economies.

Andrew Mountford, professor, Royal Holloway, University of London: I expect the UK recovery will continue to be slower than most other developed economies that have managed the pandemic more successfully. Comparing GDP growth is problematic due to methodological issues and so employment levels are a better guide and these do provide evidence of a relatively slow UK recovery, eg https://voxeu.org/article/economic-impact-coronavirus-uk-businesses, https://www.oecd.org/employment-outlook, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn02784/. One aspect of the past year that has surprised me has been the lack of a rise in unemployment following the end of the furlough. Overall employment levels are still lower than pre-crisis levels, (by about half a million in November), but this is manifested in a drop in labour force participation and a tight labour market for those participating see https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/labour-market-statistics-november-2021

John Muellbauer, professor, Oxford university: Not at the bottom but near the bottom of the pack of the G7 economies. Delayed responses to Omicron are likely to cause more damage to the economy later. Brexit continues to be a deadweight burden on growth prospects.

Andrew Oswald, professor of Economics and Behavioural Science, University of Warwick: Lag behind. Why: Brexit’s repercussions can be expected to become ever-clearer.

David Page, Head of Macroeconomic Research, Axa Investment Managers: The headline growth rate for the UK is likely to outpace other developed economies — we forecast 5.2 per cent — but this still mainly reflects a catch-up with the scale of the drop in UK GDP far worse than most others. Hence in terms of the level of overall activity, we see the UK clearly recovering more slowly than the US and China and also slower than the eurozone with capacity constraints weighing on UK activity — largely Brexit related.

Alpesh Paleja, Lead economist, CBI: We expect the UK to be roughly in the middle of the pack. The recovery was initially supported by a strong vaccine rollout and high uptake, which stood in contrast to developed countries in Europe. While this gap has now largely closed, a comparatively quicker booster campaign should keep the UK a little further ahead. We’ll also see tailwinds from strong labour market activity and firm investment appetite.

However, the Omicron variant is a curveball. Should it hit activity in the UK to a greater extent than other countries — either through significant voluntary limits on social mixing or the introduction of tighter mandated restrictions — we could see the UK slip down the rankings.

Regardless, it’s likely that the UK will lag behind the US, where direct fiscal support for households has been stronger, and where there is less sign of GDP “scarring” from the pandemic. In this regard, the jury is still out on which form of policy support has been most effective (ie furlough/job support schemes vs more direct income support for households).

Ann Pettifor, director, Policy Research in Macroeconomics (PRIME): UK trade performance on imports and exports have been among the worst of all OECD economies, with Brexit exacerbating the pandemic. This significant fall in total trade (compared to 2018) is an outcome, or consequence, of weak economic activity at home. Flat business investment is an ongoing key constraint. That is why we expect the UK will perform (in GDP terms) below the level of advanced economies in 2022. Annual GDP is likely to rise by around 3.5-4 per cent (well below HMT’s ‘comparison of independent forecasts’ which range up to 8.1 per cent). UK GDP fell further in 2020 than almost all other OECD countries and ‘rose’ a bit faster in consequence in 2021, partly due to technical reasons in ONS calculations of public sector ‘production’. We consider this ‘catch-up’ has now ended. Tax rises and ‘new austerity’ measures will constrain economic activity further.

John Philpott, director, The Jobs economist, consultancy: Slightly outpace mainly because there is still some ground to make up for the relatively big hit to output during the pandemic.

Kallum Pickering, senior economist, Berenberg Bank: Last year, the UK strongly outperformed initial expectations and should do so again. Despite the UK’s unique Brexit related challenges and persisting global supply chain issues, which hurt trade and consumption and create uncertainties which may impact investment, underlying fundamentals are healthy. Consumers benefit from record-high net worth, booming labour markets and a huge pile of excess savings. Businesses are posting a record number of job vacancies and solid investment intentions. The banking sector is well capitalised and can supply credit at affordable rates to households and businesses. Economic policy provides a tailwind. Alongside other major advanced economies, the UK is likely to continue to grow at a rate well above its long-run potential even after real GDP exceeds it pre-Covid level in Q1 2022.

Christopher Pissarides, Regius professor of Economics, London School of Economics: It will lag behind because (a) Brexit and uncertainties about trade are still present, (b) the government’s troubles, inflation and the fact that the Omicron variant is having a bigger impact on society here than elsewhere are big sources of uncertainty. I am fearful of the consequences without knowing exactly what to expect

Ian Plenderleith, chair, Sanlam UK: Drag behind, because of drag from Brexit and unstable politics.

Richard Portes, professor of Economics, London Business School: Lag. Covid-19 and incoherent policies.

Jonathan Portes, professor of Economics and Public Policy, King’s College London: The key UK-specific factors for the year ahead will be fiscal policy, where significant tax rises will be implemented in April; and Brexit, where the additional trade barriers with our largest trading partner that were introduced in January 2021 will be supplemented with additional import controls in January 2022. So while global influences (most of all the pandemic, but also US monetary policy) will dominate, the UK is likely to underperform somewhat.

Vicky Pryce, chief economic adviser and board member, CEBR (Centre for Economics and Business Research): It is not surprising that the UK economic growth outpaced those of other G7 nations in 2021 given the sharper fall in GDP in 2020 compared to most others. But GDP looks like it was still further below pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021 than those of other nations, including the eurozone, For 2022 it is unlikely that this better relative performance will be repeated as the fresh Covid-19 outbreaks, planned increases in stealth taxes via the freezing of income tax thresholds and the rise National Insurance contributions will have exacerbated the negative impact on the growth of a continuing poor trade performance post Brexit. The worsening inflationary pressures will also reduce real personal disposable incomes further and slow spending and growth.

Thomas Pugh, UK economist, RSM: The UK economy will grow by 5 per cent in 2022, depending on the development of the Omicron variant. That will be faster than the US and the EU. However, growth rates are telling a distorted picture at the moment. The main reason the UK will experience faster growth next year is because it experienced a much bigger fall in output than most other developed economies in 2020 and therefore has more room to catch up. If we take where we think the UK economy will be at the end of 2022 compared to where it was before the pandemic, then the UK is still likely to be lagging behind the other major developed economies.

Sonali Punhani, chief UK economist, Credit Suisse: Slightly Outperform. In the winter, Omicron is likely to slow growth, on top of other headwinds such as supply and labour shortages, rising gas prices and withdrawal of fiscal/ monetary support. But the accelerated booster program and high take up of vaccines, especially among the elderly, can potentially put the UK in a better place to deal with rising cases of Omicron over the winter. Once winter passes, the economy should recover on the back of strong household and corporate balance sheets, a tight labour market and robust wage growth and healthy investment inventions. But effects of Brexit are likely to linger- reduced trade with the EU and labour shortages should continue to weigh on growth.

Morten Ravn, professor, University College London: It will continue to lag behind. The pandemic is still not under control, UK public debt is high and it will be hard to engineer either a stimulus or a significant tax reform. Moreover, Brexit is having a real economic impact now. In addition, UK’s productivity problem still needs to be resolved.

Ricardo Reis, professor of Economics, LSE: Probably it will lag behind, as there is less fiscal stimulus than either the US or EU and the continuing negative effects of Brexit on trade and growth will drag it down (with none of the supposed less regulation or lower taxes in sight to pull it up).

Phil Rush, CEO, Heteronomics: The UK’s growth will probably be above its peers again in 2022 for the same reason as in 2021. The economy had to climb out of a deeper hole, raising growth rates from the bottom and dragging it out for longer. In level terms, the UK will probably remain a global laggard.

Holger Schmieding, chief economist, Berenberg: The UK will modestly outpace other developed economies in 2022. Having been far behind most other economies in 2020, the UK still has more room to catch up with the countries that managed the pandemic better. The UK will narrow the gap but probably not catch up fully with the eurozone in terms of its GDP relative to its pre-pandemic level.

Yael Selfin, chief economist, KPMG: While the UK is likely to be ahead of other developed countries in the vaccination programme, the impact on supply chains could be more acute, while labour market shortages may also prove more persistent.

Andrew Sentence, senior adviser, Cambridge Econometrics: I can’t see any reason why the UK should outpace other developed economies in terms of growth in 2022. Underlying productivity growth is weak and there is a limited pool of unemployed workers to draw on, as the high level of vacancies indicates. So I would expect the UK to be an average or below average growth performer in 2022.

Philip Shaw, chief economist, Investec: Mechanically, UK growth looks likely to be outpaced by that of its European peers, largely because its initial post lockdown rebound took place earlier in 2021 and that the current strength of natural gas prices looks set to make a bigger dent on UK household finances than those on the Continent. It is too early to tell where Omicron variant related restrictions will have a bigger impact. Britain might enjoy slightly faster growth than the US, partly due to the uncertainty over whether President Biden’s $1.75tn Build Back Better bill will get through the Senate and if so, in what form.

Andrew Simms, co-director, and research associate, New Weather Institute, and Sussex University, Centre for Global Political Economy: The UK is likely to lag behind other developed economies in things that matter — such as meeting climate targets and reversing inequality (or ‘levelling-up’) — because while the government is fond of making impressive-sounding promises, it appears allergic to developing and implementing the policies needed to make them happen.

The task of re-engineering the economy to operate within climate targets, reviewed only weeks ago at the critical Glasgow Climate Summit, has huge implications and opportunities across all sectors. Yet, as the chief executive of the official advisory body, the Climate Change Committee (CCC), said at the time, “The government is nowhere near achieving current targets.” The reason this matters so much is that, apart from being needed to preserve the ecological conditions in which the economy and society can function, it is now a binding macroeconomic frame with a target of cutting emissions 78 per cent by 2035.

But, as the CCC note, on the current lack of progress, the UK will be adding to a target busting temperature rise of 2.7C by the century’s end. More worryingly the CCC say that this can ‘in theory’ be brought down to just under 2C — but still well short of the 1.5C needed. For a rough handle on what this means in practice, for people in the richest 10 per cent globally, emissions need to drop to one-tenth of what they are set to be in 2030. Conveniently, a rule of thumb is that the carbon footprint of taking a train is one-tenth that of flying. Emissions reductions are needed for the UK of something like 12 per cent year on year.

But a quick look at recent government policy crumbles any confidence of a strong link between targets and action. In Rishi Sunak’s Budget, he famously failed to mention climate at all. Beer was referred to more than the critical threat to humanity. Instead of encouraging a shift from aviation to train travel, he halved air passenger duty on domestic flights — the most easily replaced by train travel. The long-lived freeze on vehicle fuel duty was maintained, alongside spending to expand the road network that dwarfs public investment in low carbon transport alternatives. These are all things that extend and lock-in the UK’s addiction to a polluting, high-carbon economy.

Compare this to the move in France to ban short-haul, internal flights where a train journey alternative exists or Paris’s plan for major car reduction that includes the removal of 70,000 car parking spaces. Or, the case of Oslo in Norway going substantially car-free.

The UK also needs to guard against a rush of ‘greenwash’ and false solutions. Already there is far too much reliance on carbon offsetting, when a study for the European Commission showed that 85 per cent of the offset projects fail to reduce emissions, and only 2 per cent with a high likelihood of reducing emissions.

The CCC highlight a £50 billion annual investment gap up to 2030 for the UK to be on course to meet its targets. In the United States, although many were disappointed, President Biden’s Infrastructure Bill allocated over $100 billion towards public transport and rail — with job creation a major part of the rationale. If comparison with the US feels unfair, the UK government could do worse than look at South Korea’s green new deal investing over $60 billion to lower emissions and create 650,000 jobs by 2025.

By contrast, the UK Chancellor allocated £4.8bn to a levelling-up fund to cover the remainder of this parliament — which even when added to the modest sums for green spending, to use the language of budget commentary still looks like very small beer. It is also a missed opportunity to achieve multiple goals at once through investment in a green new deal that could target much-needed home energy efficiency and renewable retrofits and green transport infrastructure. If the government is remotely serious about levelling up, it’s worth remembering that post-unification, the levelling up process in Germany took around took €2tn over 25 years.

Nina Skero, chief Executive, Cebr: We expect the UK economy to expand 4.7 per cent in 2022, slightly above the rate of growth anticipated for the United States and large European economies (4.0 per cent-4.5 per cent). While the Omicron variant poses a downside risk for economies across the world, the UK government has signalled that it will continue to provide fiscal support (eg the hospitality and leisure sector funding announced in the days before Christmas) to help ease the impact of any restrictions or even the impact of voluntary consumer caution.

Should further lockdowns be enforced, this would lead us to downgrade our forecasts, although with businesses and consumers now well-versed in ‘lockdown living’ we would expect any contraction in economic output to be far milder than that of spring 2020.

James Smith, economist, ING: The path of UK GDP is unlikely to look that different to Europe in 2022. Omicron almost certainly means a hit to January output, though GDP will likely be very close to pre-virus levels again by the end of the first quarter. Beyond Covid-19, the consumer faces a challenging few months on higher inflation — perhaps a little more so than continental Europe, given the more noticeable withdrawal of economic support from the government, as well as the UK’s greater exposure to natural gas price spikes. But 2022 could see the return of investment, which has been effectively flat since the 2016 referendum. Corporate balance sheets are in decent health (on average) and higher investment intentions are no doubt being aided by the government’s super-deduction.

Andrew Smith, Economic Adviser, Industry Forum: The UK will lag behind next year as the policy is perversely tightened in mid-pandemic. The OBR’s forecast of another year of 6 per cent GDP growth is entirely dependent on an unprecedented 10 per cent jump in consumer spending — at a time when real incomes will be squeezed by high inflation on the one hand and tax rises on the other. The numbers only add up with the heroic assumption that the personal sector finances a catch-up binge with it’s Covid-19-swelled cash balances — but these are unevenly distributed and, at the end of the day, there are only so many extra meals out anyone can stomach. Under the circumstances, the BoE’s monetary tightening can only be described as kicking the man/woman when they are already down.

Andrew Smithers, founder, Smithers & Co: Lag I hope. Money supply is growing too fast and needs to be slowed.

Alfie Stirling, director of research and chief economist New Economics Foundation: The least bad economic forecasters for some time now have been epidemiologists. In the short- to medium-term, most things continue to be largely contingent on the evolution of the virus. Honing in on a narrow time period like a single calendar year means things like the geographical origins of future variants of concern, and the timings of different waves across countries, will likely prove the crucial variable in comparative economic performance. At this stage, none of this is possible to predict, least of all in economic models.

Outside of future waves of infection, I would expect the UK to be closer to the middle of the pack in terms of the rate of recovery next year, compared to other developed economies. The UK still has further to go in order to catch up pre-Covid-19 levels than many other countries. All else being equal this would imply a greater potential for faster growth. Offsetting this, however, at least to some extent, will be the effects of Brexit in terms of labour shortages and trading frictions. Not only will this be a drag on the rate of recovery in the short term, compared to other countries, but it is also likely to limit the overall potential for a full recovery in the medium- to longer-term too.

Gary Styles, director, GPS economics: The UK is likely to outperform the US and European economies in 2022. However, this position is unlikely to be sustained in 2023. The UK economy suffered a much deeper slump in 2020 than many other economies and is therefore expected to recover more of this lost ground in both 2022. Furthermore, as the UK has been hit by the third wave of Covid-19 (Omicron) earlier than most it should be able to recover more quickly than other economies.

Suren Thiru, chief economist, British Chambers of Commerce: The UK will almost certainly lag behind most other developed economies in 2022 because the economy is more exposed to the ongoing impact of Covid-19, staff shortages and supply chain disruption.

A greater reliance on household spending to drive growth leaves the UK more susceptible to the impact of new Covid-19 restrictions and renewed consumer caution amid rising infections. The prospect of ongoing post-Brexit disruption is likely to exacerbate the squeeze on growth from staff and supply shortages, compared to other developed economies.

Consequently, the UK economy is only likely to return to its pre-pandemic level in Q2 2022, behind many of our international competitors. We now expect UK GDP growth of around 4 per cent for this year, lagging most other developed economies, with the likely exception of Japan and Germany.

Phil Thornton, director, Clarity Economics: Lag behind. In 2022 (as in 2020) economic performance will be driven by the response to the next evolutions of the coronavirus pandemic and by the endogenous state of the economy. At the turn of the year, the reaction function appears damaged with politicians contradicting scientists and politicians with the ruling party disagreeing with others, quite fundamentally. One issue will be whether the government will be able to use fiscal levers to ameliorate the impacts of future lockdowns, as and when they arrive

Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist, Pantheon Macroeconomics: The UK economy probably will remain the G7’s laggard in Q1, as it has tended to underperform when Covid-19 is in the ascendant, due to the relatively large share of consumer services activity in GDP and higher uptake of homeworking. The recovery in exports also likely will continue to fail to keep up with those in other advanced economies, due to the drag from Brexit. But the UK economy will not be alone in 2022 in enduring fiscal tightening and high inflation. British households also have amassed a larger stock of “excess savings” during the pandemic than their European counterparts, suggesting that they will be better placed to spend more even though their real incomes will be falling. So by the end of the year, the UK probably will be in the middle of the G7 pack.

Kitty Ussher, chief economist, Institute of directors: The UK will lag other economies but the effect will be slight: the headline is still that ours is an economy that wants to grow and demand will remain strong.

The lags come from two sources. First, UK macro performance is particularly dependent on household spending which is more sensitive to changes in the path of the pandemic. Second, our adjustment to life outside the EU is still ongoing so we will experience greater trade friction at our borders than other comparable economies.

John Van Reenen, School professor & director, POID, London School of Economics: Lag behind — the impact of Brexit (especially on services) will hold us back

David Vines, Emeritus professor of Economics, Oxford university: I expect the UK to lag significantly. In the short-term, the spike in Covid-19 cases is likely to be severe and to provoke the need for a longer lockdown than in other countries which have dealt with Covid-19 more intelligently. In the longer term, the damage from Brexit is likely to be severe. I think that the estimates of the effect of Brexit by the Office of Budget Responsibility are, if anything, likely to be over-optimistic. We have yet to see the full consequences of Brexit for the financial sector. And I am particularly concerned about the way the UK is likely to be shut out from European co-operation, and funding, in scientific research.

Sushil Wadhwani, chief Investment Officer, PGIM Wadhwani: The UK economy is likely to lag other developed economies during 2022. Factors that might contribute to its underperformance include the fact that labour supply problems appear to be more acute than many other developed countries. This might, in part only, be explained by Brexit and its impact on migration. Not only will supply act to directly limit UK growth but there will be associated demand effects too. The wage inflation we see is likely to elicit much more monetary tightening here than is likely in, say, the eurozone, Japan or Australia. Over time, this should slow the UK economy relative to its peers. Another risk we need to monitor is the reluctance of the UK government to provide assistance to businesses suffering on account of the Omicron wave. Consequently, we could end up seeing more scarring than was true after the first wave.

Martin Weale, professor of Economics, King’s College, London: It will lag behind with the continuing drag of Brexit

Simon Wells, chief European economist, HSBC: If you look at forecasts for 2022 economic growth, it looks like the UK will outpace most large economies. But this partly reflects a lower starting point. We expect UK GDP to return to pre-pandemic levels of activity in Q2 2022, about six months later than the eurozone and a year behind the US.

Peter Westaway, chief economist, Europe Vanguard: I had previously been expecting the UK to grow more quickly than other developed economies in 2022, mainly because it still had the most lost ground to make up following the pandemic-induced fall in activity.

But now, given the further slowdown caused by a combination of consumer reticence and new government restrictions, it’s not conceivable that the UK will be hit more severely than the rest of Europe and certainly than the US.

Overall, still a decent chance the UK will be among the countries with the highest growth rate, even though the level of activity still lags behind its pre-pandemic trajectory by more than many.

Michael Wickens, professor of Economics, York and Cardiff Universities: Slightly outpace if current trends continue. The dangers are more unexpected Covid-19 infections and whether the Bank decides to control inflation

Trevor Williams, professor, Derby University: Will lag as the recovery is running out of steam, and the Brexit effect of a labour market shortage hits productivity.

Stephen Wright, professor of Economics, Birkbeck University: Very little to go on. All the obvious bad stuff due to Brexit is likely to be masked by whatever happens with Covid-19. Since we’ve gone into Omicron earlier than most, maybe we can get out of it sooner, which may allow the UK to be ahead for a while. But that’s about the best we can hope for.

Linda Yueh, Adjunct professor of Economics, London Business School: The UK economy is likely to grow in line with other developed economies with similar levels of vaccinations. The IMF forecasts place the UK slightly behind the US in 2022 and ahead of continental Europe and Japan, for instance.

To what extent will the Bank of England be in control of inflation by the end of 2022?

Melanie Baker: Inflation is likely to peak in April 2022 in the UK and be substantially lower by the end of the year which will make the Bank of England appear more in control of inflation. Key to whether they are in control of inflation will be what happens to wage growth and to inflation expectations. Raising rates in December against a deteriorating growth backdrop is a good downpayment against inflation expectations de-anchoring.

Kate Barker: Being prepared to act now should dampen the propensity for higher inflation to get baked into expectations. However, the labour market has tightened significantly for several sectors and risks remain to the upside.

Nicholas Barr: Upward pressure on prices arises in part from higher public spending related to the pandemic but in part also because of significant pandemic-related structural adjustments. The latter are likely to continue beyond 2022, so inflationary pressures will remain.

Ray Barrell: Inflation some two per cent above target is not inflation out of control. We are going through a period of large changes in relative wages and prices. This is best managed with inflation noticeably above two per cent so fewer firms have to cut prices. Energy prices are likely to be permanently higher. Some firms will go out of business and industries shrink because of the impact of Covid on consumption patterns. If there are no more deep structural shocks inflation could be back down to around two per cent by early 2023. The Bank can manage the process.

Martin Beck: By the end of this year the forces which have pushed inflation up so rapidly in recent months should be exerting the opposite effect. Even a stabilisation of oil and energy prices at current high levels would exert a strong drag on inflation in the second half of this year. And a rotation of consumer demand from goods back to services as Covid impacts fade, combined with extra capacity to produce components and other inputs coming on stream, should bring down goods price inflation. Meanwhile, structural forces which threaten persistently higher inflation are lacking. Workers’ bargaining power may gain from lower inward migration and greater respect for those doing essential, if low paid, jobs, but we won’t see a return to the 1970s. And as long as the Bank of England continues to respect its mandate, while taking advantage of the flexibility it possesses in achieving the 2 per cent inflation target, it’s hard to see how persistently high inflation could arise. But while inflation should be heading back to the 2 per cent target by the end of this year, this will have very little to do with the Bank of England’s actions.

David Bell: Its armoury to control supply-side inflation is limited. Interest rate increases have little effect on increases in the prices of final goods, components, and raw material inputs when these are primarily driven by international shortages. Interest rate increases at the level currently being envisaged will not quell wage growth, but we will not have a return to a 1970s style wage-price spiral due to the substantial reduction in the strength of collective bargaining that has taken place since then.

Philip Booth: It is unlikely to be in control if it keeps responding to supply shocks such as the discovery of new variants by loosening monetary policy. Each time inflation rises, real interest rates fall. So, without a deliberate rise in rates, even if the Bank does nothing policy is, in effect, loosening. The Bank of England seems to have lost interest in inflation.

Nick Bosanquet: It will not be in control: inflation likely to be 4 per cent at end 2022. Inflation can be temporary due to single shot external cause such as energy prices . . . or it can become a self-sustaining process with multiple causes over a period of time. Shortages and price rises for key raw materials this year will lead to price increases for finished products next year. On OECD data 70 per cent of firms expect to raise prices. The high inflation problem will run into 2023.

Erik Britton: Define ‘in control’ . . . Most likely, inflation will gradually drift back down towards the target, but there is almost an equal likelihood that inflation expectations will slip their anchor and that slippage will be accommodated by the Bank, perhaps with an eventual shift to a higher inflation target (which the Bank would doubtless still describe as inflation being under its control). Higher inflation uncertainty now than at any time since the early 1980s. Close to a bimodal forecast distribution, rarely seen in the wild.

Jagjit Chadha: An operationally independent central bank with a floating exchange rate chooses the inflation rate it wants in the medium term. And inflation does seem likely to fall over the course of 2022 but more so if the Bank could be clearer about its reaction function and the preparedness to raise interest rates from extraordinarily low historical levels. The ground for quantitative tightening must be prepared and some mapping out of how we will return to normal interest rate levels.

Victoria Clarke: We expect that the Bank of England will hike again in early 2022 and return Bank Rate to its pre-pandemic level of 0.75 per cent in 3Q22, as it judges that actions speak louder than words when it comes to guarding against second-round inflationary risks. But we remain cautious about the breadth of current inflationary signals and still see headline CPI inflation above 3 per cent as 2022 closes. Importantly, with one legacy of the pandemic a smaller economically active population, and with some activities (like healthcare) likely to hold more workers than normal as we ‘live with Covid’, we think this should continue to underpin stronger pay awards. We do not expect core inflation to dip below 2 per cent at all in our forecasts out to end-2023.

David Cobham: More or less, interest rates will rise at some point and some of the supply-chain-induced inflationary pressures will subside.

Brian Coulton: Inflation should be falling by the second half of next year as global consumer durable goods prices stabilise and energy shocks unwind. But services inflation will rise somewhat and keep core inflation above 2 per cent. Global shortages of consumer goods could last longer than expected which is an upside inflation risk. Wages could also accelerate by more than expected, although the recent change in direction of monetary policy should help anchor inflation expectations.

Diane Coyle: It depends entirely on how the Monetary Policy Committee responds between now and then. Inflation isn’t out of control yet.

Bronwyn Curtis: The Bank of England will underestimate the level of inflation. Inflation will fall from 5 per cent plus levels, but it will still be closer to 3 per cent than 2 per cent by the end of the year. The Bank of England will be slow in raising rates.

Paul Dales: By much more than it is now! By the end of 2022, we think that inflation will have fallen back from a peak of just above 5.0 per cent in April 2022 to between 2.0 per cent and 2.5 per cent. We suspect it will fall further to the 2.0 per cent target in early 2023. That’s partly based on our assumption that the boost to inflation from global costs and shortages will start to ease from the middle of 2022.

This explains why we think the Bank of England will raise interest rates only twice in 2022 (to 0.75 per cent) rather than the three to four times (to 1.00-1.25 per cent) the financial markets appear to be expecting.

Richard Davies: I expect the Bank to be in control of inflation. I think the public understanding and intuition for where inflation is coming from (Covid and Brexit supply shocks, ie transitory) is greater than commentators imagine. So even with inflation far above target, I don’t expect long term damage to (ie rising) inflation expectations. Overall, on inflation, the Bank of England performance has been strong since 1992 and I expect the Bank to be able to ride this out.

Howard Davies: They started tightening too late so inflation is likely to persist through 2022 and beyond.

Melissa Davis: The combination of easing supply-chain pressures, commodity price annualisations, some mean reversion in tradable goods prices and slowing growth mean inflation should be back at target by the end of 2022 — and it could even undershoot, depending largely on the evolution of commodity prices. The challenge for the Bank is to strike the right note between maintaining credibility now and not undermining the recovery in 2022/2023.

Paul De Grauwe: The Bank of England will have control of inflation by the end of 2022. The factors that drive the inflation surge (high demand and disrupted supply) will abate.

Panicos Demetriades: The Bank of England has already signalled that it will not allow inflation to get out of control with its surprise rate increase on 16 December but the question is at what cost.

Covid is wreaking havoc on supply chains, while the rise of Omicron is generating additional uncertainty about the ongoing recovery. Raising rates now may be too early as the recovery may yet reverse if a new lockdown is deemed necessary for public health reasons. However, the Bank is clearly worried about the outlook for inflation to raise rates now. Its dilemma is certainly tougher than that of other central banks in developed countries because of the effects of Brexit on the supply chain, labour shortages and trade costs. These are definitely interesting times for monetary policy!

However, trying to keep inflation under control by suppressing demand in the face of multiple supply shocks could make the Bank very unpopular, if its rate hikes continue in 2022.

Rate hikes will slow down the recovery and cause misery for homeowners with variable-rate mortgages. They will not solve supply bottlenecks, solve labour shortages or reduce trade costs.

What the UK needs is not a tighter monetary policy but a competent government with a structural reform agenda that would mitigate the adverse effects of Boris-style Brexit.

Wouter Den Haan: It is hard to know whether the Bank of England will be able to get inflation back to target without knowing what shocks will hit the economy, but the UK is blessed with a very capable team on the Monetary Policy Committee.

Swati Dhingra: Will try but there are too many inflationary pressures and structural problems.

Charles Dumas: By the end of 2022, the inflation picture will look very different globally, thanks to a sharp reversal of goods price inflation. Large parts of the supply side have adapted to accommodate high Covid prevalence, partly thanks to strong investment in software, but also thanks to strong Chinese capex in the medical goods sector, and robust investment at the global scale in manufacturing. Even if the Omicron variant scare rises, demand for consumer durables associated with the “Zoom Boom” will be much less than in previous waves, making for a significantly more modest inflation shock. Looking through Omicron, goods deflation in H2 looks set to be amplified by RMB depreciation as China hits its debt wall.

Indeed, the inflation threat for 2022 could come from periods of low Covid prevalence, as supply capacity on both the capital and labour side has atrophied. When Omicron recedes, demand will surge back to in-person services, but supply is now becoming inadequate. Overall, we think the bullwhip-down effects will still dominate.

In short, while inflation anxiety is likely to build into the new year, the narrative could shift dramatically in the second half. It’s important to realise, however, that Covid is endemic, and if it remains deadly, the direct effect on the economy over the longer term could be to raise inflation. This results from the bifurcation of supply-side resources to cater for periods of both high and low Covid prevalence, while Covid-sensitive demand will only ever land on one side of this supply bifurcation at any given point in time; supply is built ex ante for both worlds, but demand is only ever in one world at a time. That means an inbuilt insufficiency of supply, and repeated inflation shocks, followed by periods of demand deflation. The supply side is not yet fully adapted to that reality, however, meaning the bullwhip-down effects are likely to dominate in 2022H2.

Wohlmann Evan: We expect inflation to moderate in 2022 in line with slower growth in economic activity and a very gradual tightening in monetary policy. The acceleration in wage growth will likely prove temporary and remain concentrated in those sectors where labour supply is tightest. That said, the risk of higher and more persistent inflation poses a risk to the recovery, particularly if the currently high levels of inflation start to become embedded in wage negotiations.

Noble Francis: The Bank of England has consistently underestimated inflation as the supply side issues and sharp energy cost rises spread across the economy. The Bank of England is likely to increase its base rate two further times during 2022 but interest rates will still remain below 1 per cent. Whilst this will have an impact on demand pull inflation, it is unlikely to impact significantly on cost push inflation. Energy costs will be less of an issue in the second half of the year as will some supply bottlenecks but other supply constraints will only be resolved in the medium-term. As a result, UK CPI inflation will slow in the second half of the year but will still remain above the Bank’s target at the end of 2022.

Former senior official: I don’t think they have lost control of inflation but with wages likely to respond to prices (and public service wages rebounding) inflation is likely to hold up for most of this year even if interest rates continue to rise.

Andrew Goodwin: I don’t think the Bank of England has lost control of inflation in the first place. The vast majority of the overshoot this year has been due to factors outside of its control, and these pressures should melt away during 2022. From my perspective, the idea that the Bank of England needs to tighten policy to maintain its inflation-fighting credibility is overblown.

Andrew Hilton: Again, who writes these questions? To what extent are any central banks ‘in control’ of inflation if (for instance) inflation is caused by an exogenous shock like an oil price rise, or if it is caused by an unprecedented fiscal response to a pandemic? The implicit assumption is that it would be a failure if the central banks were not ‘in control’ — but that may simply not be the case.

My view (FWIW) is that inflationary expectations are rapidly becoming anchored, and that it will be very difficult indeed for the Bank to turn them around. That means a base case CPI rise in (say) 2/2 2021 of circa 6 per cent.

Dawn Holland: A lot depends on the evolution of the pandemic. I would expect underlying inflation to be broadly under control, but bottlenecks and cross-border transport costs may continue to exert upward pressure on the headline rates.

Paul Hollingsworth: We expect inflation to still be more than 1pp above its 2 per cent target by the end of 2022, with greater signs of underlying inflationary pressures and lingering risks of above-target inflation persisting. That said, the monetary policy tightening cycle should be well under way at that stage and inflation should still be on a cooling trajectory — we would not characterise the Bank of England as having “lost control” of inflation.

Ethan Ilzetzki: This is entirely up to the Bank of England, which has the tools to bring inflation down. The decision to increase rates on December 16th was a small, but important and, in my view, correct decision. It indicates that the Bank will attempt to rein in inflation, but time will tell. Inflation now exceeds 5 per cent, while real interest rates are below -3 per cent: a highly accommodative stance. Yes, uncertainties about the pandemic and the recovery abound, but none of these can be rectified with low interest rates.

Dave Innes: While the current spike in inflation is worrying, its drivers remain mainly transitory. I expect fuel prices to stabilise and supply issues to subside in 2022 and consequently inflation will begin to come down, but still remain high at the end of 2022.

Dhaval Joshi: The Bank of England’s monetary policy, which works by choking and stimulating aggregate demand, is ill-placed to ‘control’ inflation in 2022.

This is because the current surge in inflation is nothing to do with overheating aggregate demand. UK aggregate demand, even after its strong rebound, is still struggling to get back to its pre-pandemic trend. Meaning that aggregate demand is weak.

Instead, the current inflation comes from the massive and unprecedented DISPLACEMENT of demand from services into goods, combined with an inability to increase goods supply quickly enough. To the extent that I expect this displacement of demand to correct, inflation should cool in 2022.

But crucially, this rebalancing of demand will happen irrespective of Bank of England policy.

So I think it would be a huge mistake to connect cooling inflation with monetary policy. In that important sense, the Bank of England will not be “in control” of inflation in 2022.

Deanne Julius: I expect the Bank will raise rates at least to 1 per cent by the end of 2022. This should have a cooling effect on the housing market, but is still below zero in real terms so is not likely to depress business investment.

Saleheen Jumana: Being in control of inflation means different things to different people. Unanticipated shocks make it impossible for inflation to remain at target at all times. I interpret being ‘in control of inflation’ as a situation where the average rate of inflation stays close to the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target.

We forecast inflation will fall from its current highs of around 5 per cent to less than 3 per cent by the end of 2022, as energy prices fall and the ongoing boom in consumer durables slows. That would take average inflation, over the five years ending 2022, to less than 2.5 per cent. That is close enough to 2 per cent, for me to conclude that the Bank of England will be in control of inflation by the end of 2022.

Markets are worried that the UK is entering an era of high inflation, like the 1970s. We are at a critical moment. There are risks that inflation could remain elevated for longer, should energy prices spike, supply chain disruptions persist or if labour market scarring ends up being more severe. Equally, inflation could be lower than expected if the new Covid variant, Omicron, has a large negative impact on consumer demand.

Lena Komileva: Inflation is largely the reflection of structural factors which are beyond the power of the Bank of England to control, but which will also exercise oversized control over Bank of England policy going forward.

For a fuller discussion see my FT column of July 2021: The answer to inflation fears lies in ending Covid disruption

https://www.ft.com/content/e79c894e-8e89-44c6-a864-c6a2cc70bbb0

Barret Kupelian: Evidence from the Bank of England itself shows that deviations from its 2 per cent inflation target are driven by food, energy and imported prices almost two-thirds of the time are driven by global food and energy prices, FX movements and domestic tax changes. These are factors that are outside the direct control of monetary policy and most of the factors that have led to the high level of inflation in the UK are outside of the control of the Bank.

However, subject to the Omicron variant not leading to a massive upheaval of economic activity, I expect that the supply-chain pressures will abate towards the end of the year. We’ve seen some evidence of this happening in December and, if this trend continues, we should expect it to manifest in retail prices in the second half of the year. This should then give the appearance that the Bank (and indeed other central banks in advanced economies) have some control over the inflation rate.

Ruth Lea: Inflationary pressures, as we know, have been largely supply side/cost phenomena (supply shortages, rapid increases in fuels) & not “controllable” by the Bank. And this could well continue to end 2022. However, the Bank should be seen to act on the demand side to (try to) prevent “second-round” effects.

John Llewellyn: Unless the Johnston government uses its majority to limit the jurisdiction of the Bank, as it is threatening to with the courts, the Bank will be in control of inflation. But that will mean that it cannot be in simultaneous control of real GDP.

Gerard Lyons: The Bank of England has badly misjudged the persistence of inflation in the UK. I do not expect this rise in inflation to prove permanent, but it is not passing through quickly as the Bank expects and instead is persisting. Thus, the scale of the stimulus in 2021, particularly QE, was unnecessary.

Inflation will remain elevated and exceed the Bank’s 2 per cent target throughout all of 2022 and settle above the target in 2023. In that context, it would be premature to conclude the Bank will be in control of inflation by the end of 2022. Although the initial cause of this inflation shock was outside of the Bank’s control, it must be mindful of second-round effects.

That being said, annual inflation should be much lower at the end of 2022 than at its peak. I expect the annual rate of inflation to peak in the second quarter, around 7 per cent, and to decelerate from August onwards.

The economy faces a double whammy at the start of the year, from the consequences of Omicron and a cost-of-living crisis as inflation rises, and thus monetary policy should remain on hold in early 2022.

But as the economy rebounds and as the year progresses, I would expect the Bank to tighten policy, with interest rates returning towards 0.75 per cent, the pre-pandemic level, by year-end. This will also trigger some quantitative tightening, with the Bank having already outlined that a higher bank rate will trigger a reduction in its stock of purchased assets. With parts of the economy vulnerable in the wake of the pandemic, tightening by the Bank needs to be gradual and predictable.

It is not just about monetary stability in terms of curbing inflation, but the Bank’s actions, including low rates and QE, are also risking financial stability.

Steve Machin: It should be, but we will have to see if it can get back to the targets.

Christopher Martin: This all depends on whether price inflation leads to wage inflation. I suspect it will not, because the power of workers over wages has declined over the past 20 years. But that is just a guess. No one can make a confident prediction at this point.

David Meenagh: The Bank will be slow to increase rates and therefore I think inflation will still be significantly above the target by the end of 2022.

Milas Costas: To control inflation in 2022, the Bank of England needs to stop following Sicilian philosopher Gorgias and his ideas outlined in his famous work “Non-existent”. Gorgias put forward three arguments: that nothing exists; that, even if something in fact existed, it could not be properly known; and that, even it could be properly known, it could not be communicated through language.

What we did learn from the Bank of England in 2021 is that inflation pressures do not exist because current inflation is due to supply-side bottlenecks; that even if inflation pressures did exist, these could not be properly known (or measured) because of pandemic distortions; and that, if a proper plan of monetary policy was in place, it could not be communicated through language. Which explains, of course, why politicians and the media dubbed current Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey, like his predecessor Mark Carney, the “unreliable boyfriend”. For starters, the Bank could adopt a more flexible monetary policy in terms of combining small in size Bank rate hikes with reductions in QE without conditioning the latter on the policy rate reaching 0.5 per cent.

Patrick Minford: Interest rates will need to rise to 5 per cent or close, which will restore control.

Andrew Mountford: The Bank of England doesn’t have a great deal of control over pandemic induced supply shortages and these appear to be behind much of the current increase in inflation in many economies. Indeed tightening credit in response to such supply shocks may do more harm than good.

John Muellbauer: Annual inflation is still likely to be running at 4 per cent or higher by December 2022. It is a global problem, with the US having continued high inflation given labour shortages due to early retirement and long- Covid, and the housing market still running hot.

Andrew Oswald: Very little. It is currently hard to view our nation as having an independent Central Bank.

David Page: To a large extent. By the end of 2022, we expect headline inflation to be falling back quickly towards the Bank of England’s 2 per cent mandate, with an expectation for it to fall close to it in 2023. However, the UK labour market does look tight and we expect it to warrant monetary policy tightening across the course of next year to ensure that the Bank of England’s target is consistently met looking through into 2024.

Alpesh Paleja: It’s clear by now that inflation is going to rise further, thus the risk of it becoming embedded in domestic price and wage setting is higher. The Bank’s signals on future monetary policy — ie a few rate rises to come beyond December and a strategy for “quantitative tightening” — are welcome, and at this stage seem sufficient to get price pressures under control.

But the risks to inflation are very much to the upside, even after the emergence of the Omicron variant. Indeed, this could actually exacerbate price pressures, through stoking supply chain disruption and further skewing global demand towards goods (at the expense of consumer services). If it materially dampens domestic demand too, it might leave the Monetary Policy Committee walking something of a tightrope when it comes to monetary policy.

Ann Pettifor: The extent to which central banks are ever ‘in control’ of inflation is much exaggerated, save where they choose tight monetary policy to engineer recessions via mass unemployment — as in the 1980s. The factors underlying current inflation are mainly outside central banks’ monetary policy toolkit control. We think CPI inflation will remain well above 3 per cent in 2022 but will fall back in the latter part of the year. House price inflation is due to wider global financial market excesses — which central banks decline to constrain. As in previous instances, financial markets will panic in the face of tightening monetary policy and central banks will likely ease again.