Base of the iceberg: the tragic cost of concussion in amateur sport | Concussion in sport

Paul Wheatley is often in bed by 7.30pm. There is little else to do once locked in his prison cell well before the sun’s light fades. So he reads a bit, then attempts to drift into unconsciousness.

It is the only sure way to push out the voice which follows him everywhere. The one most familiar and cherished in his world frantically repeating his name, each an anguished attempt to rouse him from a seizure before they were off the road and the tree appeared and it was too late.

It is Maria’s birthday tomorrow. His partner of 23 years would have been turning 69. That date, 10 May, is not a good one for Wheatley. That one, and 23 February – the day Maria was killed in the car he was driving.

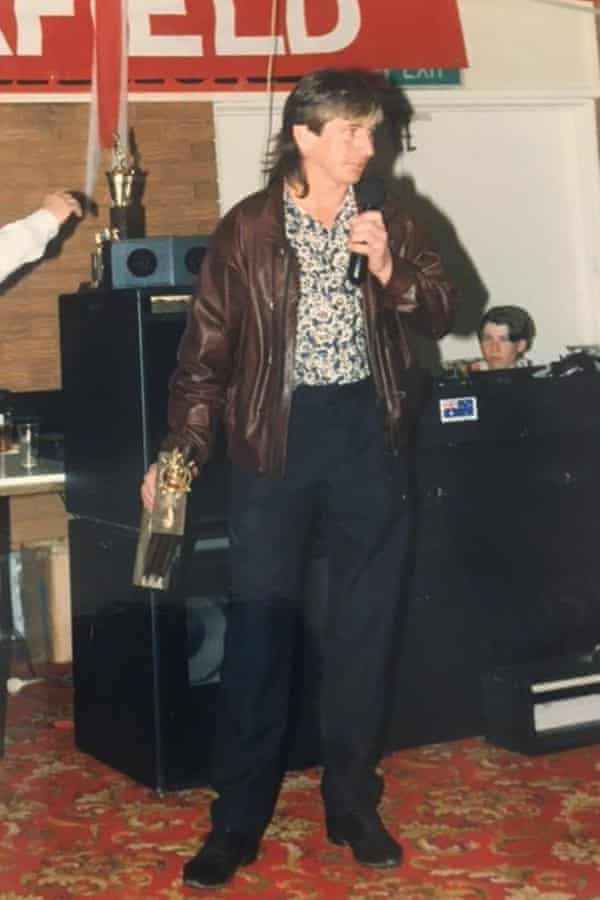

Standing at 170cm, Wheatley is short. The type of short that does the gritty, grunty work in a game of footy. That tackles low and hard and gets knocked about a lot. The 61-year-old played 200-odd games for Victoria’s Fairfield Football Club over a decade and copped, at an estimate, at least one hard hit to the head every fortnight. One was a knee which left him with a hole in his skull. The groove can still be felt today, underneath his tufts of silvery hair.

Wheatley’s brain isn’t what it used to be. He has temporal lobe epilepsy, a condition his treating neurologist, Professor Chris Plummer, has potentially linked to these recurrent brain injuries. It is an epidemic affecting a generation of contact-sport participants. And, as the majority of public conversation centres around first-grade athletes, there are many, many more playing grassroots codes every weekend. All possess identical brain matter to their elite counterparts.

The high-profile cases are piling up. Earlier this month, All Blacks player Carl Hayman said he had been diagnosed with early onset dementia at the age of 41. Just days later, concussion forced Wallabies full-back Dane Haylett-Petty into retirement. They come as the coronial investigation continues into the death of former Richmond footballer Shane Tuck, who was posthumously diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

These are the tip of the iceberg; beneath the surface floats a much larger mass.

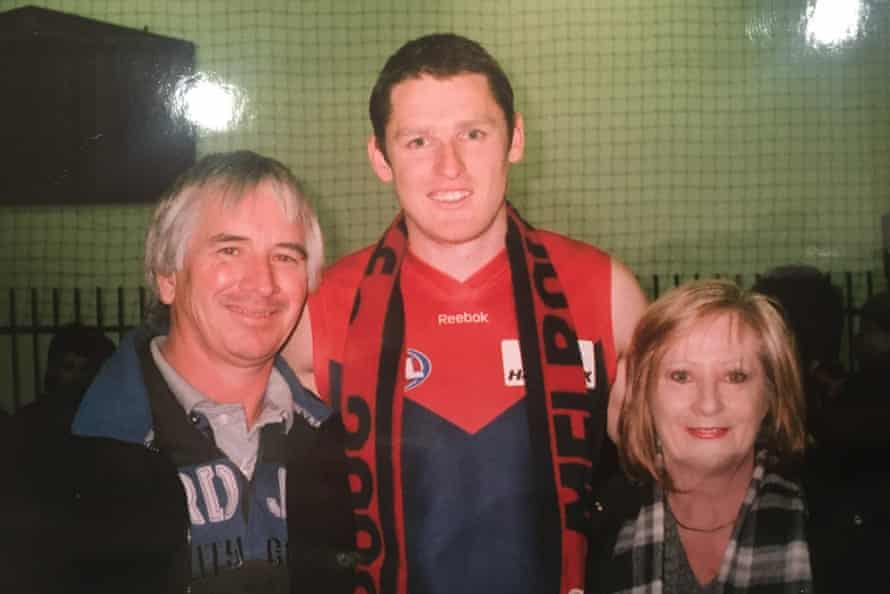

“He copped the same knocks,” says Wheatley’s brother John, the father of former Melbourne AFL player, Paul Wheatley, who is named after his uncle. “It doesn’t matter what grade you’re playing; when you get hit, you get hit. Unfortunately, when we played, that was part of the game.”

For the senior Paul Wheatley, that part of the game could have landed him in jail, convicted of manslaughter and dangerous driving occasioning death, and sentenced to five years and two months behind bars.

The accident occurred before Wheatley came under Dr Plummer’s care and what happened is described by Wheatley’s sister, Annitta Siliato, as “an unbelievable set of circumstances – like a movie”.

St Heliers Correctional Centre, on the outskirts of the mid-north NSW town of Muswellbrook, is a minimum-security facility. This place is not like Mid North Coast Correctional Centre in Kempsey, where he had a knife pulled on him and was not given the correct dose of medication. Or Grafton, where he was bashed by another prisoner. Or, indeed, Long Bay Gaol, where he saw brawls over access to the phones.

Here he can read, sometimes watch Carlton play on TV – his mum sends newspaper clippings of the fixture – and walk unhassled laps around the yard. He is even allowed to earn $35 a week working in the cordoned-off garden section reserved for well-behaved inmates.

But the past four and a half years have been a lesson in grief, crippling depression and a legal and prison system foreign to any first-timer, all while coming to terms with an illness which has so profoundly altered the course of his life.

Wheatley’s epilepsy is a serial loiterer. It sits on his shoulder and steals his memories before they can take root and floods his neural pathways as his brain tries to communicate with his muscles.

On one occasion in jail, while in the shower, he awoke on his feet to feel burning-hot water scalding his thigh, seemingly unable to move as he watched his skin welt. Another time, he came to on the grass outside, unsure of how he got there.

In AFL terms, the 1980s and ‘90s were the hardman years. They were the days of David Rhys-Jones, Dermott Brereton and Robert DiPierdomenico. In essence, they were a time of being tough. And if you weren’t, at least acting like it.

On a local field, in a much lower grade, Wheatley was doing his best to fake it until he made it. He was 26 and hadn’t played since doing his knee as a teenager, so it was with initial reluctance that he joined his brother John at Fairfield.

He enjoyed the sport, having been a regular spectator at Carlton games with his late father. But he was also unconvinced his 70kg frame would cut it. He started on the wing and ended up a rover in the middle. The less he held back, the more confident he got. His dad had always told him to bump them before they bumped you. So he gave and took whacks for 10 years, and his more significant head knocks numbered in the hundreds.

“He was always in the bottom of the pack,” says John, whose son, Paul Wheatley Jnr, played almost 150 AFL games for the Demons between 2000 and 2009. “I’m surprised I haven’t got any problems – I wasn’t much different to him. It’s in the back of your mind, especially when you see what happened with [Danny] Frawley. I’ve been knocked out a couple of times and kept playing – no one knew back then.

“Once I missed a whole half a game and didn’t even remember it. After I had a shower, I walked back into the club room, was handed a beer and snapped out of it. It was the weirdest feeling.”

Professor Mark Cook, an internationally recognised epilepsy specialist, says the most frightening factor about the disorder’s links to collision-based sport is the inability to measure the long-term cumulative effects of subclinical brain injuries.

“Even minor head injuries are associated with about double the risk of epilepsy,” says Dr Cook, who is chair of medicine and director of clinical neurosciences at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, and a former long-time president of the Epilepsy Foundation. “And because of the difficulties measuring repeated minor injuries, I don’t think we really have a good way of figuring out how often this is the problem.”

Dr Cook says the recent post mortems of former footballers Danny Frawley, Polly Farmer and Tuck showed the players had been collecting injuries over very long periods. “And just because they’re professional, I don’t think that means they get more head knocks than amateur footballers,” he says. “In fact, the reverse might be true.”

All three were found to have CTE, which is mostly discovered in the brains of people with a history of head trauma but has recently been found in sportspeople who have not sustained a clinical concussion but multiple subclinical concussions, as was the case with Tuck.

On top of this, CTE has also been linked with epilepsy.

Signs of Wheatley’s epilepsy surfaced insidiously after he and Maria moved from Melbourne in 2016 and bought a property in the New South Wales mid-north coastal town of Smiths Lake. It showed itself via lapses in memory, pauses in speech and moments of mental absence. He went to a family function and greeted a peer he thought he hadn’t seen in years, only to be informed they had caught up the month prior.

Chris and Graeme Watt, close friends with Maria for 37 years and Wheatley the 25 since they met him, noticed a “vagueness” in the two years before the accident. “We went on holidays to Port Douglas, all four of us,” Chris says. “We were talking about it and he didn’t remember the holiday.”

Peter Kemp, who worked with Wheatley for almost 15 years and counts himself as “one of his and Maria’s best mates”, recalls Maria once phoned him after a night out in Melbourne. “She said he’d passed out and hit his head on the corner of the bench,” Kemp says. “I was with him that night and he didn’t have much to drink.”

Most telling were the brief vacant spells they now recognise as complex partial seizures. “He just goes blank, it’s quite unusual,” says Siliato. “If you didn’t really know he had it, you might not suspect he’s having a seizure. You might just think he’s sitting there staring. When you tell him he stopped talking for two minutes he doesn’t know it’s occurred.”

Maria soon learned the signs. He would appear awake but also unresponsive, smack his lips and fidget involuntarily. She took him to the GP, suspecting the memory loss was dementia. When tests returned a positive result for epilepsy his mother, also named Annitta, couldn’t figure it out. “I said that was impossible,” she says, “because it doesn’t run in the family at all.”

According to the facts relied on in the criminal proceedings against Wheatley, he was referred to a neurologist and had an initial consultation on 17 November, 2016. The neurologist diagnosed Wheatley with epilepsy and told him he would need to observe a “stand-down period” from driving for six months and inform the Roads and Maritime Services. He recalled that his patient was “very reluctant to cease driving”.

“Paul asked if the stand-down period could be shortened,” he stated, adding that he told Wheatley that, if he continued his medication and had no further seizures between then and his follow-up appointment in February, he should be able to get his licence back.

Maria rang family and friends to relay the news. “She said ‘it’s treatable, that he should be right with these tablets’,” says Chris Watt.

Wheatley was advised against driving by both the specialist and his GP, though the RMS did not officially suspend his licence until 29 January, 2017. According to the agreed court facts, a number of witnesses said Wheatley spent the intervening period hankering to get his licence back.

A neighbour and friend said he had discussed Wheatley’s “regular blackouts” with both Wheatley and Maria and that, after his diagnosis, Wheatley told him: “I still have my licence so until someone tells me otherwise I can drive.” The neighbour’s impression was that Wheatley viewed his inability to drive as a “threat to his identity”. He also felt he “was in denial about his condition”.

This is not uncommon, according to Dr Cook.

“I’m often with people when they have seizures, and when you tell them immediately after they’ve recovered awareness that they’ve just had a seizure, they say ‘no I didn’t’. Sometimes they’d become quite aggrieved that you’ve suggested it,” he says.

“It’s a strange mixture of the brain abnormality itself and the fact that it disrupts your ideas and thoughts, and memory around the time it happens, and that sometimes prevents you taking that information in.

“Sometimes people are just in denial about it, other people just don’t join the dots – and these are all normal people.”

The judge who sentenced Wheatley stated in his remarks that the GP had said that, from the date of diagnosis, he “endeavoured to inform and educate Mr Wheatley repeatedly about the risks of and gravity of driving with his diagnosis”. After Wheatley asked him to complete a fitness to drive form, the doctor opined that Wheatley either did not understand the legal requirements around his condition or was “trying to pull a fast one” to get his licence back.

Dr Cook says, from his decades of experience with epileptic patients, the reality is potentially more complicated.

“The thing about temporal lobe seizures in particular,” says Dr Cook, “is they involve parts of the brain which are fundamentally a part of the way memory works, and they disrupt it in complex ways. So when people say they didn’t know they had a seizure or don’t remember someone telling them they did, they’re probably telling the truth for the most part.”

The sentencing remarks detail concerned conversations between Maria and family members, friends and neighbours – many in Wheatley’s presence – about his continued seizures.

She had said they were “frightening” for her and that she wanted to become his full-time carer. A number of witnesses said Wheatley told them he was not aware when he was having seizures, but that he was present during discussions about them and told he should not be driving. An expert report before the court concluded that although Wheatley may not have been aware of all the seizures he was having, he must have been aware that he was having sufficient seizures not to be allowed to drive.

In all, they paint a picture of Wheatley that is blurred between unawareness and blind obstinance. Dr Plummer acknowledges Wheatley may have had “his head in the sand”. But he also believes his understanding of his condition was poor.

Dr Plummer first saw Wheatley on 28 June, 2017 – about four months after the accident – and admitted him to St Vincent’s for a week of inpatient testing, which found he was having up to several complex partial seizures each day. He asked his patient if he had ever played a contact sport.

He also says Wheatley appeared surprised when informed that epilepsy could manifest very differently to what popular culture might have him imagine.

“Lay people think seizures are only when you crash to the floor and shake all over,” Dr Plummer says. “But seizures come in different shapes and sizes, and you can just have what we call minor events, where you just lose awareness.

“That can be quite brief, but can last long enough for you to cause a lot of damage, like fall into a fire. Or crash a car.”

On the morning of 23 February, 2017, Maria drove Wheatley to his follow-up appointment with the neurologist. According to the court facts, Wheatley told him he had not had any further seizures since September the previous year and asked him to sign a fitness to drive form.

The court would later find the neurologist was “clearly and deliberately misled” by Wheatley. The neurologist told police that, had he been informed Wheatley had experienced further seizures, he would have “increased the dosage of his medication as well as apply for a longer stand-down period for his driving”.

The fitness to drive form was signed by both parties and Maria drove Wheatley to a RMS branch. With his licence newly restored, he drove them to a shopping centre to buy some groceries. Over lunch they discussed long-standing plans for a caravan trip around Australia. Then he got in the car to drive them home.

“My son rang me in the morning,” says Wheatley’s mother. “He’d been to the doctors, and he rang me to tell me he was cleared and he’s got his licence back. The next call I got,” there is a long pause, and then a breaking voice, “was the accident.”

While travelling down a quiet detour street, Wheatley’s brain went elsewhere but his foot stayed weighted on the accelerator. The car, rapidly increasing in speed, hit a tree with such force it was dislodged and uprooted. Unbeknown to him, Maria was no longer next to him, having been flung from the vehicle and then under it.

Wheatley escaped with a small scratch on his face. Police attending the scene reported him crying uncontrollably and shouting, “I’ve killed her”. A roadside breath test returned negative, and he was taken to hospital. When a doctor asked him about his epilepsy history, he said he usually asked Maria.

The following day, with the family now at Smiths Lake, police came to interview Wheatley. John remembers not wanting to let them in because Paul remained so upset. “But Paul wanted to talk to them,” he says.

Siliato says the detective that day told her he might be charged with reckless driving. A few months later, in early May, he rang to let her know Wheatley would be arrested and charged with manslaughter and dangerous driving occasioning death.

“It was just the saddest thing because my brother really loved Maria,” Siliato says. “I’m going to start crying. Just the fact that he lost the love of his life and he was responsible.”

Wheatley admitted in court that he drove at least once while on conditional bail following the accident. “It was his lack of understanding, lack of awareness,” Siliato says. “That rationalisation wasn’t there. If it was me, I probably wouldn’t drive, but I don’t have a neurological condition.”

Dr Cook emphasises that Wheatley’s case is “fairly exceptional” and should not compromise the independence of the many people with epilepsy who are able to drive safely. “There just needs to be a better system for more carefully considering each individual situation,” he says. “Not black-and-white rules, because most people with epilepsy will drive fine without any problems.”

On 18 June, 2019, at Port Macquarie district court, Wheatley was convicted and sentenced with a non-parole period of two years and nine months, having pleaded guilty to manslaughter. In a letter he wrote from jail as part of an unsuccessful submission to be granted early parole, he says he felt he had no choice but to plead guilty, citing the emotional and financial stress of the accident and subsequent legal rigmarole.

The presiding judge, Christopher Robison, noted Wheatley’s remorse over the death of “the love of his life” and said there was little doubt he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and prolonged bereavement disorder.

During his first night inside, he tried to strangle himself in his cell. It was not the first time he had tried to take his own life in the 15 months since Maria’s death, a period wracked with nightmares and heavy drinking. On one occasion, the neighbours helped him down from the roof. On another, he rowed his dinghy out onto the lake.

In jail he was closely monitored, but encountered problems of a different nature when his dose of medication was lowered. He had a seizure in the clinic and woke up on the floor. He rang his sister. “Eventually,” Siliato says, “one of the people that worked for the prison called me. They said they weren’t allowed to because there are lots of inmates who have addictions. I said, ‘but this is not an addiction, he could die’.

“So they said they had him in a cell with a camera and were watching him 24 hours, and if he had a seizure they would take him to the hospital.” The correct dose was reinstated soon thereafter and in August 2020, a letter from parliamentary secretary for health, Natasha Maclaren-Jones, confirmed that “regrettably, since June 2019, Mr Wheatley’s seizure medication was not administered to him on five occasions”.

The other issue was Wheatley’s involuntary ticks. The audible lip-smacking and blank stare risked being misconstrued as provoking fellow inmates. That fear came to pass during his first few days at Grafton Correctional Centre, where he was bashed by another prisoner, having been placed in maximum security instead of the minimum security section for which he was approved at the time of his transfer from Kempsey. Wheatley did not press charges. A few days later, he was transferred to St Heliers.

On 10 February, 2021, Wheatley authorised concussion campaigner Peter Jess to act on his behalf for all his health, incarceration and legal matters. Jess has unsuccessfully attempted to have him released, petitioning for NSW governor Margaret Beazley to reduce his sentence under the royal prerogative of mercy. Wheatley cannot afford to appeal the rejection.

“Our criminal justice system cannot cope with trauma-induced brain damage,” Jess says. “Somebody who has structural damage such as Paul has not had the cognisance to understand what had happened.

“And the focus on the impact of brain trauma on elites has not filtered down to the grassroots, even though we are finding that the brain trauma is exactly the same at the grassroots as it is at the elite level.”

On 16 February, his application for early parole on the grounds of exceptional extenuating circumstances was rejected. He cannot afford the legal fees for an appeal, so will remain at St Heliers until his scheduled parole in March, 2022.

When the time for his release comes, he aims to help educate others. He has spoken on the phone with former AFL player Shaun Smith, who last year was awarded a $1.4m insurance payout over the brain injuries acquired during his career, and hopes to build more connections with others who played before the risks were known.

“Thankfully it’s a lot different today,” says Siliato. “But I think there’s still more awareness that needs to be out there. My daughter still plays footy, and I’m so nervous. Every game, I can’t relax. I never used to be like that.” It is why she has set up the Head Knock Foundation, and hopes to educate schools and sporting clubs, and create a support network for sufferers.

Wheatley is doing better than before. There is still too much time to think in jail, and he will stay on his antidepressants. And even as the outside world beckons, he knows it comes with the continued estrangement from Maria’s sons, who cut ties with their stepfather after their mother’s death. Maria’s family were contacted by Guardian Australia but declined to be interviewed.

The concussion cause, at least, is something to hold onto. “My brother has been through such a traumatic experience, he is lucky to have survived,” Siliato says. “He doesn’t really have much in life, but this gives him purpose.”