As long as there are Tom Wilsons of the world, there will be NHL Emergency Assistance Fund

“That [figure] remains fairly constant from year to year,” Bill Daly, the NHL’s deputy commissioner, said last week in a phone interview. “That sounds right in the zone.”

Established some 75 years ago as a financial safety net for ex-players, PEFA is funded solely by fines and suspensions to the current working help, as meted the last couple of decades by the Department of Player Safety. It’s there if needed, and scores of ex-players have been helped through the years, albeit through the unintended largesse of the bad characters who continue to make their donations.

Fans of a certain age might remember that it was Gary Bettman, new on the job as commish, who in 1993 headed a committee that slapped Caps winger (sound familiar) Mark Hunter with a 20-game suspension for his brutal hit on Islander center Pierre Turgeon in the ’93 playoffs. DOPS soon evolved, appropriately removing the role of player discipline from the list of responsibilities of the game’s No. 1 administrator.

Headed into the weekend, according to Daly’s figures, roughly $600,000 in fines and suspension were assessed in the first two months of this season. That sum included the $5,000 fine Alex Ovechkin was assessed for driving a pitchfork-like two-hander into Trent Frederic’s groin.

If bad behavior weren’t as certain as water freezing at zero degrees centigrade, the fund might have to look for other means of filling the till. For now, PEAF isn’t faced with holding any bean suppers.

As long as there are the Wilsons of the world, and a fan appreciation for violence, there’s little chance of a funding shortage. Some years just yield bigger bounties than others.

“The fund — which pre-dates me by many years — has been instrumental in helping a lot of players,” Daly said. “I think since 1990 we’ve had in excess of 400 players, or player families, or people from the NHL family, who have received assistance from the fund.”

Ex-NHL executive, and for years the league’s one-man disciplinarian committee, Brian O’Neill oversaw PEAF long into his retirement from his day-to-day administrative duties. His successor, Hall-of-Fame center Pat LaFontaine, now 56, is now president and runs the fund with six other board members — three each from the league and player union sides.

“Pat is perfect for this job,” Daly said. “First of all, he stays in touch with the all the players. He has it deep down in his heart, the right and wrong, and he’s very sensitive and sympathetic to issues that players go through. He’s been fantastic so far. And … he’s lived it.”

LaFontaine, 33 when he retired after 865 games, might have played longer had it not been for excruciating post-concussion issues he dealt with for years, related in part to a vicious Jamie Macoun stick smash to his face and jaw in November 1991.

The fund in recent years, said Daly, has expanded its giving scope, aimed in large part at helping current players, such as with programs emphasizing career development and career/lifestyle transitions.

“So they don’t find themselves in a situation after their career where they need assistance from the fund,” he said.

One thing that has remained a constant over the years is player reluctance to reach out for help. Daly noted the fund itself is better these days about reminding current players and alums that the fund is there if needed.

But hockey players are a stubborn, proud lot. These are guys who learn at a young age to spit out broken teeth and skate directly to the bench for their next shift, or stay out on the penalty kill even on a broken leg (see: Gregory Campbell, 2013 playoffs, drilled by an Evgeni Malkin slapper).

Rarely, noted Daly, is it the player himself who raises his hand. A referral can be made from anyone — family member, friend, or anyone in the hockey community — and then the fund can connect with the player and, if he’s agreeable, the due diligence around a formal application process can be performed and vetted by the board’s executive committee.

“Some of that is reluctance to ask for help, for sure,” Daly said. “But sometimes it’s just because they don’t know they need help. Everybody knows when they’re in a financial crunch, I suppose, but this fund deals with issues beyond that — whether it be mental health, or whether it be substance abuse, or whether it be a number of different issues. Those cases get referred to the emergency assistance fund quite often.”

Knock out the knockouts

Why does the league still put up with dangerous hits?

Wilson, who did not appeal his suspension, will be back at work March 20 against the Rangers, 15 days removed from bum-rushing Carlo to the injured reserve list.

The Bruins as of Friday night offered no timeline in regard to when Carlo might be back in the lineup, or at least be able to resume skating. They also have to confirm his injury as a concussion.

The incident once again raised an old suggestion that the perpetrator in these instances should be forced to sit out as long as the victim. In the case of Patrice Bergeron getting clobbered in October 2007, that would have meant Flyer defenseman Randy Jones would have been sidelined, like Bergeron, for the remainder of the season.

While all of that may seem fair, just and tidy, the argument against quid-pro-quo side-linings is that the team with the injured player could keep him out of action, even if he were returned to good health, as a means to keep the perpetrator from returning to play. The process then would have to be monitored by medical professionals charged with assessing whether the victim was ready to return, still hurt, or malingering. Not a good answer.

It’s also a very tricky process around concussions, which often cause emotional/psychological issues that can’t necessarily be detected by standard testing or examination. A concussed player can look OK, and test OK, but that doesn’t mean he feels OK to resume play.

Meanwhile, Wilson, all 6 feet 4 inches and 220 pounds of him, will return healthy, locked and loaded and free to identify his next prey. History has shown it won’t take him long. He is a man with size, speed and skill, a unique package that mitigates any need for him to go that one step beyond that thus far in his career has earned him 30 games in suspensions.

Question is, and one that never gets answered, is why do the league, the Players’ Association and even teammates and coaches suffer such fools? It was hard to fathom in the Original Six days when players earned chump change, and all the harder now with overall player compensation hovering around $2.5 billion per annum.

Players have been the most valuable part of the game since the drop of the first wooden puck, and that $2.5 billion figure serves nowadays only to underscore it. Yet the NHL remains the lone professional sport, outside of boxing, UFC and bullfighting, that still allows fighting — and forever misses opportunities to put an end to seek-and-destroy tactics such as Wilson employed on Carlo.

DOPS easily could have tagged Wilson with 20 games or more. The hit was that brutal, that obvious. In 2013, DOPS tagged Bruins forward Shawn Thornton with 15 games for his ugly takedown, slewfoot included, of Brooks Orpik, plucking the then-Penguins defenseman out of a standing scrum and then punching him a couple of times while flat on the ice.

Thornton was among the game’s best punchers, but never a dirty player or a discipline problem. He got tagged with 15, while Wilson, 23 games worth of suspensions already tucked in his dossier, received less than half.

DOPS, in this case, delivered with the same efficiency as the on-ice officiating crew that didn’t so much as assess Wilson with a minor penalty. It failed to do its job. It failed the Bruins and Carlo and itself.

Above all, it failed the league’s integrity and its inherent charge to provide a reasonably safe workplace with defined rules, acceptable conduct as codified in the rulebook and, if needed, adequate and appropriate supplemental discipline.

We can argue all day, and into the next millennium‚ as to the definition of reasonably safe. It has been argued around the game for decades. It’s indeed a violent game, often dangerous when played even within the acceptable range of checking and hitting. For those who love hockey, very few, if any, want that taken out of it. Hits sell. Tempers sell. The blend of tumult and skill are its marrow.

Yet, as an industry, the NHL continues to suffer fools like Wilson. He will age out, weaken, and one day be gone, possibly when the next iteration of himself belts him silly, addles him along the boards or catches him with a bareknuckle right that knocks him to Palookaville. It ends for them all, one way or the other. The league, meanwhile, accepts it, condones it, and awaits the next one.

Like Wilson, the NHL knows better, but just can’t help itself.

Open net

Why haven’t Bruins re-signed Rask or Halak?

Jordan Binnington, less than two years removed from leading the Blues to a Cup title, agreed Thursday to a six-year contract extension that will carry a $6 million cap hit. It begins next season and his peak earning years, years three and four, will pay $7.5 million.

For a legit No. 1, that’s reasonable money, and Binnington has worked himself into the conversation of franchise goaltenders. His name on that Cup in ’19 put him in that discussion.

There remains, however, the standard caveat regarding his relatively low game count. Headed into weekend play, he had worked only 102 regular-season games. There is no standard measure of predicting long-term success for goalies, but a résumé of, say, 200 games would afford more assurance. Of course, it also might have boosted his annual wage to $8 million or more, so both sides were hedging a little around that $6 million figure. He would not be the first “hot” tender, sized up for long-term success, to disappear into mediocrity or worse.

Meanwhile, Binnington, 28 in July, exits stage left from the free agent market, which is currently headlined by Pekka Rinne (Nashville), Frederik Andersen (Toronto) and the both Bruins tenders, Tuukka Rask and Jaroslav Halak.

It remains, shall we say, curious the Bruins seem content to be midway through this season without either Rask or Halak inked to extensions. Both are on expiring deals, Rask at $7 million and Halak at $2.25 million. Free agency begins July 28, which as of Sunday is on 136 days down the road.

In the unlikely scenario both Rask and Halak were to walk, that would leave GM Don Sweeney with perhaps a Dan Vladar/Jeremy Swayman combination to take into 2021-22, or a visit to the UFA market.

Both Rinne and Andersen are finishing up deals that carry a $5 million cap hit. And though Rinne has the greater body of work, he is 38 and Andersen 31, compared with Rask, 34, and Halak, who will be 36 in May.

Not on the list

Cashman reached mark, but was not Bruin draftee

A note in this space last week detailed the 13 Bruins draftees who reached the 1,000-game plateau. One other career Bruin, Wayne Cashman, also reached 1,000 games, but was not included in the list because he was not a draftee.

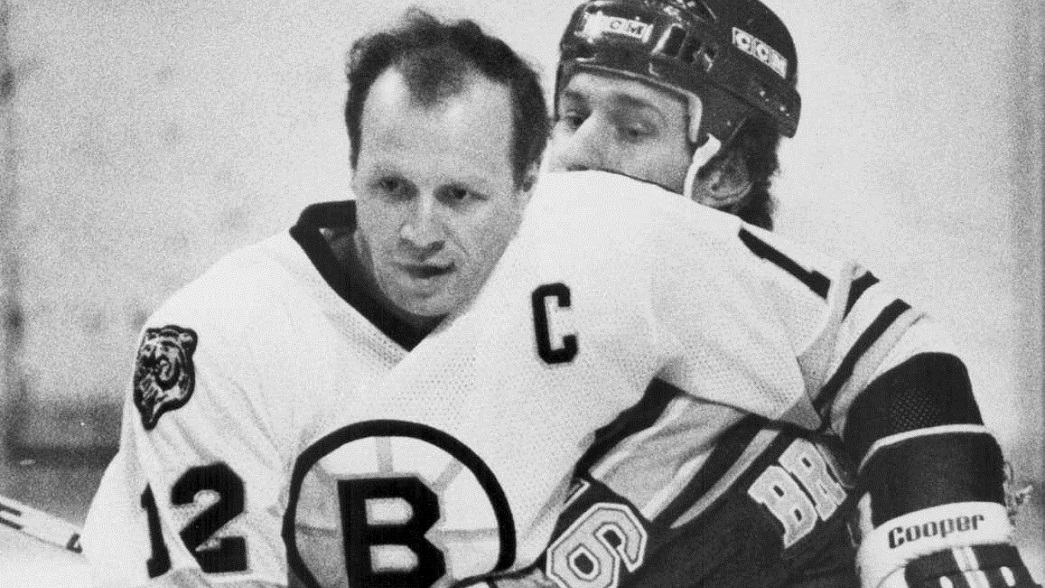

Cashman, now 75, was similar to the likes of Bobby Orr, signing with Boston in years prior to the creation of the draft in 1963. The Bruins owned his negotiating rights by virtue of the protected territorial rights the six-team league used prior to ’63.

Cashman, Ray Bourque, Don Sweeney and Patrice Bergeron are the only four Bruins to start their careers here and play in 1,000 games or more in Black and Gold. Cashman stands as the lone one in that group to retire and never play elsewhere, though it’s likely Bergeron and possibly David Krejci ( will join him.

John Bucyk played 1,436 games for the Bruins, but began his NHL life playing 104 games for the Red Wings prior to being swapped for legendary tender Terry Sawchuk. That deal, by the way, is believed to be the only one-for-one swap in league history involving two players later named to the Hockey Hall of Fame —Sawchuk in ’71 and Bucyk 10 years later, following his retirement in the summer of ’78.

Cashman’s all-Boston career line: 1,027 games: 277-516—793 and 1,039 penalty minutes. And the odd two-hander across the shoulder here and there.

Loose pucks

Why ESPN ever told the NHL to go fry ice more than 15 years ago, who knows. But it’s back, and that only bodes well for a sport that still has wide open acreage to seek new viewers, especially in the United States. The new deal, which begins in the fall, will pay upward of $3 billion over seven years. If you’re scoring at home, that’s around $100 million per franchise, less what the league itself skims as operational vig. Another US partner soon will be named, be it Fox, or possibly a re-committed NBC, which did a superb job the last 10 years or so, allowed to fill the void ESPN created when it offered the NHL mere scraps after the lost lockout season of 2004-05 … Evgeni Malkin, during a Zoom session this past week when asked what the Penguins could use to become a serious Cup team again: “Maybe Mario Lemieux?” … Best of luck to Dale Arnold, who on Friday co-hosted his final talk segment on WEEI, though he will continue there with some Red Sox play-by-play work, and his studio role at NESN during Bruins broadcasts. During his long WEEI run, he was often the lone voice to talk hockey, other than to use it as a sophomoric comic device to ridicule the sport, the Bruins and especially their fans and media contingent. The environment improved, albeit ever so slightly, particularly in the wake of the Cup win in ’11. Like hockey guys do, Arnold stuck with it, right to the final horn. Here’s wishing him an extended overtime, with more room on the sheet.

Kevin Paul Dupont can be reached at kevin.dupont@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @GlobeKPD.